Warm guts dripped from my hands as I reached for the space bar. The YouTube video I was watching, “Respectful Chicken Harvest Part 2 of 2,” had gotten ahead of me, and I needed to rewind and figure out what exactly the lovely woman meant by “just kind of squish everything out.”

“Is she pushing or pulling?” I asked my friend Chris.

“It’s more of a scooping,” he said. “You’ve got to get your hand in there and separate the tube from the body.” So I again slipped wrist-deep into the bird and was rewarded with a wet sound somewhere between deathly suction and a lively fart.

We were in his kitchen in Bushwick, Brooklyn. The day before, I’d asked him a question that I’ve been asking lots of people lately: “What can I learn from YouTube that will make me a better person?”

His response, “Learn to butcher an animal,” was so fast and certain that I should have suspected something, but I didn’t, so I said yes, and suddenly, he had a partner in this unpleasant chore, and I had blood on my hands and innards on my keyboard.

We’ll get to what I learned later. For now, let’s talk about why.

In the past year, I’ve turned to YouTube to figure out how to repair an electric hot water heater, tie a Windsor knot, clean a motorcycle carburetor, clip my dog’s toenails, replace cracked floor tiles, and do dozens of other chores that I’m not particularly equipped to handle but am entirely capable of accomplishing with a little guidance.

I’ve also sought advice on more oblique topics, like public speaking (breathe), shaving a tricky patch near my Adam’s apple (make a C with the razor), asking a woman to marry me (it will always be romantic), and whether a dirty joke could work in my wedding vows (no).

In sickness and in health and for better and worse, I asked, and YouTube answered, so I got it in my head to ask even more, to go bigger. That’s why I started asking, “What can I learn from YouTube that will make me a better person?”

When I queried my mom, she paused in a way that indicated she needed some clarification.

“YouTube—the thing on the internet where you can watch videos,” I told her.

“Yes,” she fired back. And then she paused in that motherly way that makes clear she’s considering how not to offend me: “You need to learn to listen.”

When I called my sister to complain, she blurted out, “You need to get over your road rage.”

When I told my wife all this, she said, “I was thinking you need to be more like a Jane Austen heroine: Play piano, speak French, draw, that sort of thing.”

So that’s how I made my list: Butcher an animal, listen better, overcome road rage, and draw well. That’s what I was going to try to learn from YouTube.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that learning to play the piano requires possession of a piano.

I can’t find an official figure for the number of video tutorials on the site, but there must be millions. They range in subject from computer programming to nunchuck technique to dancing at the club (with separate videos for men and women). There are professional grade how-to’s posted by the marketing arms of billion-dollar companies that live alongside unedited cell-phone videos of little kids explaining how to rent a movie from a Redbox machine. Neither type is necessarily going to do a better, or worse, job of teaching me what I actually want to learn, which is also part of the fun.

YouTube is a murky fount of wisdom—a wise parent who has had a few drinks, an expert after hours, a therapist who doesn’t care whether you’re asking for a friend, and also a weirdo in a bus station who says he knows when the Weehawken Express leaves and then shows you his dick.

With that in mind, I started cautiously looking for answers.

Listening better means a lot of things to a lot of people, but almost everyone who has committed to making a YouTube video about it agrees that listening is different from hearing. Understanding that is one of the keys to becoming a better listener, apparently, so I file that nugget away after a painful hour spent watching listening-focused TED talks, straight-to-camera sob sessions, and management videos done in a style I associate with workplace harassment training.

When my wife gets home and we settle into our evening routine, I try hard not to merely hear her but to listen. I follow her recap of the day with thoughtful questions. I ask about coworkers and friends. She doesn’t want to tell me more about her meeting or her lunch or the subway. “Keep listening,” says the voice in my head, but then my wife asks, “Why are you making a weird face?” And I have to explain that I’m “listening.” She tells me to stop.

An iteration of this happened every time I remembered to listen. People always noticed when I tried, and I didn’t always remember to try because I was busy doing other things, important things like working and having fun and not making the people I’m around feel uncomfortable.

“Learning to listen is hard,” I admitted to my mother during one of our Sunday check-ins. “What?” she said. “The dog has something. I’ll call you back.”

Getting over road rage is a tougher nut to crack. Most of the videos I uncover have some variation of the words in my search query, along with “Russia” or “Russians” (“How Russians Deal With Road Rage”; “This Is How You Deal With Road Rage in Russia”; “How to Handle a Road Rage Misunderstanding, Russian Style”; “How to Deal with Road Rage the Russian Way”; etc.). Mixed in with those, there’s an absolutely terrifying video of an Australian motorist stalking and repeatedly ramming the car of another driver, some very unfunny parodies, a couple of videos that teach people how to cope with aggressive drivers, and a little animated film that tells me I should sleep more, build extra time into my trips, and tape a picture of my loved ones to the dashboard. Done. Easy. Fine.

I don’t really have a road-rage issue anyway. I’m not some maniac who follows people, menacing them. I’m just a guy who has spent the last dozen years driving in and around New York City, mirror-to-mirror with hundreds of thousands of the most self-interested, rude, incompetent, disgusting, motorists on the planet. I’d argue that my rage is a logical consequence of everyone else being an asshole. My sister would disagree and probably point to a recent trip from JFK to my apartment.

I was well rested and had set aside plenty of time. Better than pictures, I had actual loved ones in the car—my sister and her son. We were waiting in traffic, merging from the Grand Central Parkway to the Long Island Expressway, when some guy lunged his minivan in front of us without signaling. It was crazy and scary and totally unnecessary, saving him maybe 10 seconds of travel time. In response, I ignored him. I just kept inching forward like he hadn’t sneaked in front of me, and he kept inching forward until we were engaged in this game of slow-speed lane-changing chicken and my sister screamed, “Stop it!”

We spent the next hour fighting like teenagers. One week later, I’ll admit that the guy driving that minivan (whose license plate number I committed to memory) is a monster, and that YouTube has not helped me tame my baser instincts.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that learning to play the piano requires possession of a piano. Learning French is a road I’ve been down before. So my wife’s Jane Austen self-improvement suggestion left drawing as the only reasonable exercise. Also, rendering tasteful nudes and country gardens is entirely in line with my retirement aspirations.

YouTube is home to way more drawing tutorials than I am willing to sit through, so I picked one with a lot of views (“Tips to Draw Better in 6 Minutes - The Line”) and then continued my artistic education by watching a handful of clips by the same instructor, a trim, middle-aged Italian man named Leonardo Pereznieto, who uses the screen name Fine Art Tips and reminds me of that skeazy high school teacher who had a penchant for massaging girls’ shoulders.

Under his slightly creepy, yet skillful guidance, a few old tricks come back to me, and a handful of new techniques for shading, determining scale, and drawing what I see trickle into my brain. Almost immediately, I’m certain that this foray will be the most successful, so I start planning a dinner party with Pictionary for dessert.

“Sand” was my first word. Despite a fairly legible drawing of a beach and an hourglass that looked like a pimply no. 8, no one got it.

“Migrate,” was next, resulting in a flock of elongated m’s and guesses including “snoring,” “Mary Poppins,” and “the Milky Way,” before I scribbled a map of North America with a legion of stick figures moving from Canada to the U.S. That did the trick, and I was feeling good until someone asked, “How did you get migrate from a hockey team?” I excused myself to get a drink.

I have a vague sense of how to remove the insides of a chicken, but I’m not about to jump on the line at the local poultry slaughterhouse.

Butchering an animal turned out to be dealer’s choice: Chris picked the Respectful Chicken Harvest series for us. I watched both parts before the bloody deed and had to go back to them as we got to work, a fact I’m now reminded of nearly every time I set hands to my computer keyboard.

Haunting memories aside, we managed to turn living, organ-filled, feather-covered animals into naked, hollow, protein in a few hours. Over supper, I noted that the rich flavor and tough meat paired perfectly with the pride and guilt I felt while eating what I’d just killed.

Despite the fact that this whole lesson was a manipulative scam, the apocalyptic paranoiac in me is happy to have gone through with it. Still, it’s hard to say how much I actually learned. I mean, I know what a “killing cone” is now, and I have a vague sense of how to remove the insides of a chicken, but I’m not about to jump on the line at the local poultry slaughterhouse and show the old pros how to sling guts. I was clueless before the video, and I’m just barely a novice after, which is maybe the point.

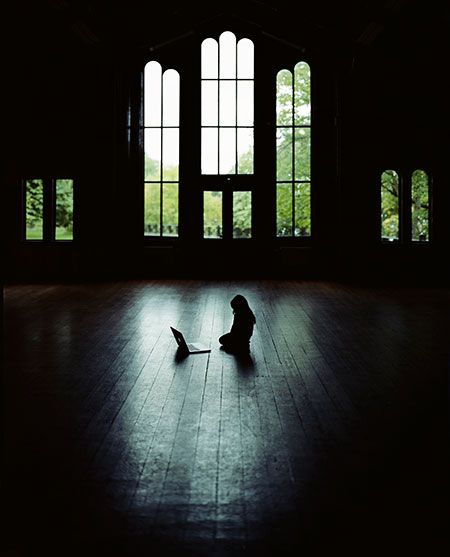

YouTube offers this fantastic introduction to an experience. It gives the briefest access to billions of little worlds, but that tiny piece is only the start of learning.

Sure, when I’m at my best, I now do take a second to ask whether I’m listening or hearing—or honking as a warning or as an outlet for the poison that bubbles inside me—but those aren’t deep-seated, habituated, learned behaviors. In the heat of Pictionary, my drawing was the same palsied scribbling that it has always been, and when I walk past the poultry case at the grocery store, I don’t look wistfully at the plastic-wrapped birds and think that it should have been me who drained their blood.

Maybe that will change in time. Maybe I’ll repeat these newly learned behaviors until old-age cripples my de-boning hand and the photo of my family taped to the dashboard yellows and curls with age. And maybe YouTube will get better at sorting results, so that I can find an art teacher who specializes in overcoming my special kind of incompetence or a listening coach who doesn’t make me want to scream, “Shut up!”

Maybe I’ll get better at learning from watching YouTube. That’s a skill too. Someone should make a how-to video about that.