Just off the downtown drag in Portland, Maine, behind a door papered with laminated signs (admission is by cash only, closed Tuesdays, parking at Joe’s will get you towed, etc.) and down a long hall that could lead anywhere is a pair of rooms devoted to natural history and one man’s search for truth. In the first of these stands an eight-foot-tall Bigfoot.

The figure, which has the pelt of Chewbacca and the face of a Neanderthal, was built by Wisconsin taxidermist Curtis Christensen in 1990. For years, it was a feature at RBJ’s restaurant in Crookston, Minn., the self-declared “Bigfoot Capital of the World.” Nearly a decade ago, it resurfaced in Maine.

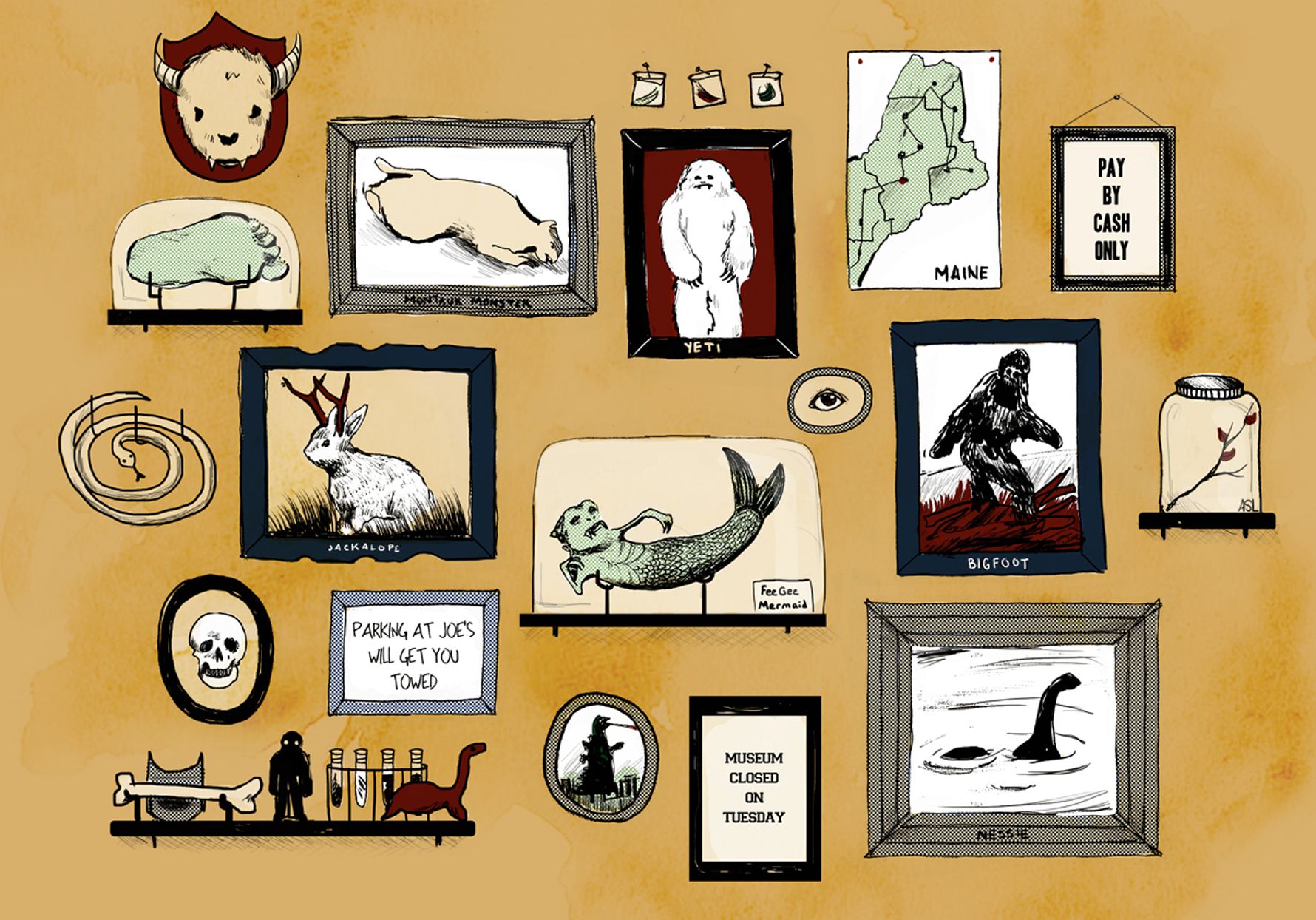

Cryptozoology is the study of hidden animals: of Bigfoot and the Yeti (both apes, but hailing from different continents), of Nessie and the Montauk Monster, and, formerly, of the okapi and the Komodo dragon. Aliens don’t figure into it, or ghosts, or zombies. Instead, cryptozoologists search for cryptids, animals heretofore considered mythical or extinct, the stuff of legend.

The International Cryptozoology Museum, which bills itself as the only museum of cryptozoology in the world, does double duty: first as a collection for scholarly work, second as an educational institution. The space is airy and light, quiet but for a little smooth jazz in the background. Its collection of artifacts numbers in the thousands, including the afore-described Bigfoot.

The room devotes itself, mainly, to natural history: Low cases illuminated by neon tubes hold plaster casts and hair samples, some noted as fakes, most offered as evidence. Bigfoot feet have, in general, toes much shorter than their size might suggest. A snakeskin (12 feet long? 20?) hangs flat against the wall. An original Macintosh sits near a filing cabinet—an artifact of the obscure like everything else. Above the bathroom door, a snarling pelt (its origin mysterious, its genus un-noted) keeps watchful gaze.

Cryptozoologists search for cryptids, animals heretofore considered mythical or extinct, the stuff of legend.

A whole cabinet is devoted to the Loch Ness Monster: mostly little figurines, many originally made as tourist souvenirs. There’s a tiki kitchen, complete with retro radios and a pair of penguins blocking access. It’s used for staff lunches and plaster cast-making workshops. Then there’s a doorway flanked with taxidermy, wild cats on one side and a beaver on the other, that leads to the inner room. A sign under the rodent, next to a figurine of Indiana Jones, asks passers-by: “Do giant beavers still exist?”

The cats are there to highlight sightings of black panthers. The beaver, meanwhile, illustrates that many cryptids are thought to be holdovers from an earlier era. Indiana Jones is just in there for scale.

The inner room, awash in color and open in the middle to accommodate a circle of kid-sized chairs, concerns itself with other aspects of the field. There’s a wall of taxidermy fakes: antlered rabbits called jackalopes and a furred trout, which is exactly what it sounds like. These are both run-of-the-mill in a certain flavor of rural general store, but the museum also has a couple renditions of my favorite fake, the Fiji (or Feejee) mermaid.

The mermaid, with the torso and head of a monkey attached to the back half of a fish, was originally one of the main attractions at P.T. Barnum’s museum, and indeed, one of the pieces on display was a prop used in an A&E movie about the great showman. It looks a bit like something you might find under a pyramid.

There is a display case of toys, icons really, of Bigfoot and the Yeti. These, a sign reads, are cultural artifacts: “moments in cryptozoology history saved from the dumpster.” On the opposite wall, a large collection of Andy Finkle paintings, flat and colorful, pop-art renditions of monsters and the men who look for them. Near the exit there’s a map of Maine with cryptid sightings marked out in pins. It’s no pincushion, but then the woods-to-people ratio up here is a high one.

The founder of this museum, the chief collector and curator of its holdings, is Loren Coleman. He is the author of an enormous stack of books, including the genre-defining Cryptozoology A to Z (written with Jerome Clark), a frequent speaker on the hidden and obscure, and a go-to interview subject for documentary makers. “I’m humbled by it,” he says of his stature in the field, and tells about a woman who came to the museum and burst into tears, she was so excited to meet him.

Coleman, who keeps his white beard neat and seems to favor sweater vests in the museum and safari vests in the field, speaks quietly and with deliberation, reminding me instantly of a high school guidance counselor. I later learn that he spent years doing research and teaching classes on mental health issues among at-risk youth, with particular attention to suicide prevention among the adopted.

Near the exit there’s a map of Maine with cryptid sightings marked out in pins. It’s no pincushion, but then the woods-to-people ratio up here is a high one.

I’m curious to discover if there is a connection between these seemingly disparate parts of his life—between working within the academy and working decidedly out of it, between talking to troubled kids and searching for signs of Bigfoot. “The work I’ve done around mental health is really around mysteries … suicide is one of the greatest human mysteries,” he told me. “So, trying to look at the mysteries of animals, from a very early age on, I knew we were animals, and there’s this kind of artificial separation. But I saw looking at mental health, looking at Freudian phenomena, looking at cryptozoology, all kind of merge—without me going fringy or crackpotty, just trying to keep very grounded in a scientific way looking at all of those. To me it’s never been separate. I see them interrelated in a way a lot of people don’t.”

Coleman grew up in Illinois and busied himself in his pre-teen years with diverse interests, but he found his true calling at age 12, when he went to see Half Human—the American version of a Japanese film called Jūjin Yuki Otoko, about the Yeti.

Jūjin Yuki Otoko, by Godzilla’s much-lauded production team of Ishiro Honda, Eiji Tsuburaya, and Tomoyuki Tanaka, seems mostly notable for its conspicuous absence from the monster-movie canon. Its depictions of a tribe similar to the native Ainu as backward inbreds worshiping a mountain monster were enough to have it banned (or at least, removed from circulation) in Japan, and it has since sunk into obscurity. Half Human is a clip job—the American producer added a new soundtrack, a few American actors, and a news-reel style announcer, making the film the object of some derision among monster film connoisseurs. Beyond any discussion of cinematography, Half Human was enough to captivate the young Coleman.

“I went to school the next week,” he told me, “and I was kind of shocked by the reaction [I got from my teachers] … like it was something beyond what they wanted to talk about in school. But luckily I had really good reference librarian friends, and one of these said, ‘Well, let me give you some books,’ and …I went home and devoured them.”

Before he was 14, Coleman says, he was corresponding with other searchers around the world, trading knowledge, clippings, and specimens: “Some days, I’d come home and there would be 20 envelopes in the mailbox.”

The museum opened on the main floor of Coleman’s home in 2003 and moved to downtown in 2009. What started as his personal collection has been bolstered by donations and the collections of other researchers who have passed away. Indeed, Coleman says, the museum is intended to serve as a home for these personal collections.

In the early days of the museum, a friend and fellow cryptozoologist passed away quite suddenly. Coleman wrote the obituary, and a few days later the man’s mother called to thank him. “And by the way, you don’t have to worry about his collection,” she said, “I threw it all in the Dumpster so nobody would have to worry.”

The way he tells the story of this call sounds almost as painful as losing his friend. Coleman had already started inviting the public into his collection, but this episode marks the point where his focus changed to museum building.

“I [realized that I] really needed to start a museum so that when people die or they’re growing old or they’re getting cancer … they know there’s one place they can donate [their collection] to. But more importantly, think about preserving it, come up with a plan that they’re happy with. ... There’s all kinds of places that preserve these things in a real nice way. I don’t feel so needy that I need everybody’s in the world, but I wanted to let people know that there’s a magnet for their collections if they can’t find other places. The whole model ... is to really put a model out there where people think, ‘This is an important sub-sect of zoology that needs to be preserved.’”

It should be said: There are other museums about cryptids. There’s the Bigfoot Discovery Museum in Felton, Calif., and the Loch Ness Exhibition Centre in the Scottish Highlands. But the International Cryptozoology Museum is the only one, according to Coleman, that takes a broad view, a survey of the entire field. If there is another, like its subjects, it is hiding well.

The diversity of artifacts in Coleman’s museum brings to mind the private Wunderkammer, literally “wonder chambers,” also known as cabinets of curiosities, that were the precursor to modern museums. Though it is safe to argue that collections have existed as long as human culture, cabinets of curiosities occupy a very specific space, namely, Central Europe in the throes of the Renaissance. Many of the era’s great collections were those of its princes: of Rudolf II (the Holy Roman Emperor) and the Medici Grand Duke of Tuscany. But as the search for natural truth reached new heights, these collections were amasseded by scholars, too. Of these, the most recognizable is the collection of Danish physician Ole Worm.

When I asked Coleman to tell me about his favorite artifact, he picked out hairs recovered by famed Yeti hunter Tom Slick in 1959.

“In the earliest cabinets,” writes Arthur MacGregor in Curiosity and Enlightenment: Collectors and Collections from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century, “priority was given to overall abundance and to the most singular exhibits.” Rarities were coveted and fakes were prevalent. Narwhal tusks were often exhibited as unicorn horn, for instance, and other pieces of the fantastic were displayed along gemstones, fossils, taxidermy, and art. By collecting as broadly as possible, curators sought to reflect the diversity of the world in which they lived, a decidedly humanist goal.

These mini-universes, these theatrum mundi (“theaters of the world”), gave way in time to catalogs and to more systematic collections, which in turn led the to birth of the modern museum. Whole tracts have been written about this development (and MacGregor’s is a fantastic survey), but two points are worth noting here. First, while both cabinet collections and later museums did much to bolster their founders’ standing socially, museums are essentially public-facing, while collections, even accessible collections, are private.

Second, as collections moved from the universalist to the descriptivist, the priorities of the collector changed. Instead of searching out the rarest of objects, collectors came to value artifacts representational of more common experience. As Antonio Vallisnieri (1661–1730), professor of natural history at Padua, Italy, wrote, “Really, what could be more useful in coming to know nature than seeing particular classes of natural bodies at the same time and in the same place … in fact, what is a museum if not the natural bodies’ index of names and descriptions.”

When I asked Coleman to tell me about his favorite artifact, he picked out hairs recovered by famed Yeti hunter Tom Slick in 1959—everyone must have a first love—but he also places special significance on a case of books and figurines concerning the Dover Demon, a humanoid with glowing orange eyes and a melon-shaped skull spotted in Dover, Mass., in 1977. Coleman led the initial investigations and coined the name. The Demon is no Bigfoot, but it’s notable enough for a Wikipedia entry, and is apparently quite popular in Japan.

We talked a little more about cabinets and museums, about public faces and private collections. Coleman is a universalist—an equal-opportunity scholar. He makes a strong case that his collection of toys is not junk (as some unkind reviewers have suggested) but artifacts of cultural anthropology, and, really, I believe him.

Cryptozoology, Coleman told me, can be a gateway science. Hook ‘em with Bigfoot, then get into the business of Linnaean taxonomies and the meaning of cultural artifacts.

A couple years back he got into a minor scuffle with the IRS—they suggested that this was all just a hobby—and one of the ways Coleman proved he was serious was by moving his collection into a space downtown. But it wasn’t just the address change he was after. Throughout our discussion, Coleman emphasized the joys of showing visitors around the museum, whether they were the older viewers of CBS Sunday Morning (which profiled the museum last November), young couples visiting Portland for a weekend of eating and shopping, or children, enthralled as he still is, with the search for Bigfoot.

“I read some of the reviews on TripAdvisor and Yelp,” he told me, “and they say things like: ‘Well, we went to the museum and thought Loren Coleman was going to be a wide-eyed weirdo, and he was really grounded, we really learned a lot, it was really scientific, and now I think about Bigfoot a little different.’”

I’m surprised that Coleman, who’s spent the majority of his life working in a field that most would scoff at, sees value in presenting his museum as entertainment. But he does: Cryptozoology, Coleman told me, can be a gateway science. Hook ‘em with Bigfoot, then get into the business of Linnaean taxonomies and the meaning of cultural artifacts. “It’s not about Bigfoot and Yeti and Nessie,” he said. “It’s really about discovering new animals. It’s fun. It’s entertaining.”

Coleman actually has a model curiosity cabinet, filled with pinned butterflies and attractive rocks. He uses it to talk to school groups about the history of collecting. But cabinets, he says, were rife with fakes, and this makes him leery of the term.

Fair enough. Coleman’s project is surely more than a cabinet , but it might just be a Wunderkammer. Sometimes old words can be best, and his is indeed a room of wonders and curiosities.