In spring, the Wisconsin Dells, “The Waterpark Capital of the World!,” is a ghost town. My summer memories were of 20 square miles of amusement parks alive with slow-moving Midwestern flesh. Everything ad hoc and dripping in roadside Americana kitsch—water parks, thrill rides, T-shirt shops, fudge stands. But on this off-season Tuesday in March 2010, the roller coasters weren’t tumbling, the parking lots were barren. The only kids peeing in a wave pool were at one of those indoor monstrosities out by I-94. This wasn’t the Dells I remembered. This was a Dells I’d never seen.

But Dan Gavinski, owner of the Original Wisconsin Ducks, was working. He moved quickly through OWD’s office, his jaw set with purpose. He seemed like the kind of guy who was always working, even when his fleet of 90 repurposed WWII troop carriers wasn’t running groups of vacationers through the wilderness on one-hour guided tours. Dan was tall and trim with dark hair, fit in a way that made it difficult to guess his age within a decade.

“So you want to work here,” he said. It wasn’t a question. He didn’t smile. Nor did he mention why, after ignoring my calls for a month, he’d decided to invite me in to talk.

In two months I planned to move from Madison to the Dells to write a book. I’d paid for my motel room in advance, though I didn’t have a book contract yet. What I had was faith, and five of eight jobs lined up. Except for this one, the most important one. I was ready to beg.

“Yes,” I said. “Very much.” When Dan didn’t answer, I added, “A lot.”

The Original Wisconsin Ducks is one of the Dells’ oldest and most iconic attractions. If Dan said no, I would lose the heart of the book proposal I’d worked on for five months—which would hurt my soul in ways that were hard to quantify, but not as much as having to slink back to my agent and tell her I didn’t have a job at OWD. This after I’d already told her I would have no trouble procuring any job in the Dells. That I’d “more or less” already procured them.

“You realize most of our drivers are in college?” Dan said. “How old are you? Thirty-five?”

“Eight.”

He nodded, his lips thinned. “In your messages, you mentioned a book. What’s it about?”

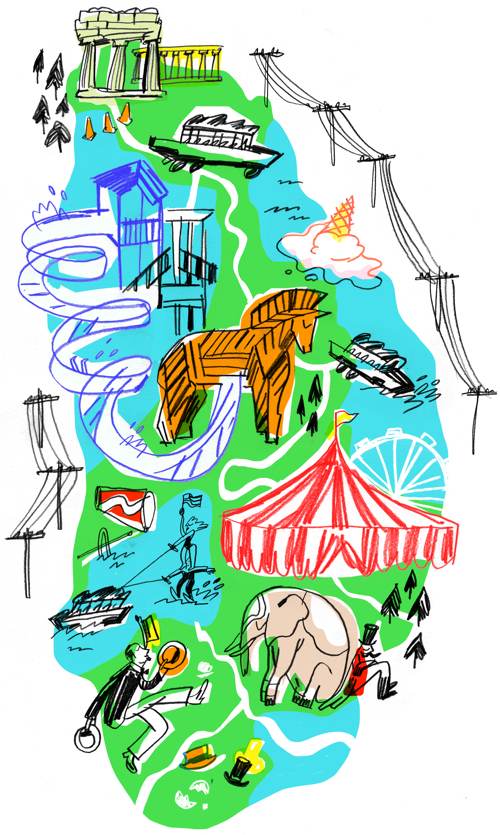

I glanced over his shoulder out the window at a 65-foot Trojan horse, Mount Olympus Theme Park’s centerpiece lawn ornament. It would have been more imposing if it didn’t have a go-kart track disappearing into its gut. Or a replica of the White House—upside down, no less—behind it.

I launched into my elevator pitch, a verbal dry heave: “I visited the Dells often as a child—now my girlfriend wants to get married and have kids—I’m a perpetual adolescent, trying to hold off adulthood—the Dells is a children’s playground—what better place to embed myself? What would happen if I worked all these crazy jobs, did it all, literally every attraction in the Dells? Kind of amused myself to death? At the end of the summer, which way would I be pushed? It’s a year-of stunt book.” I gulped for air. “You know, one of those memoirish things.”

That year, I’d moved through days seeing my name on the spine of a book. It seemed like such a good idea. My plan was airtight. But whenever I described it aloud, it always seemed to leak a little oil. I didn’t know why.

“Huh,” Dan said. He crossed his arms. “If you want to be a duck driver, I’ll hire you. I’m just worried what you’re going to write, that you’ll make fun of the Dells. These attractions pay people’s mortgages.”

“No way,” I said. “That’s not what my book is about.”

“I grew up here,” Dan said. “Started working with the ducks when I was 14. It’s my home.”

I wasn’t sure if he meant OWD or the Dells. It didn’t matter because I was looking at the horse again. I started my reporting right there, taking mental notes: Horse as metaphor. What is the horse? Me? My life? Symbol of the Dells’ emptiness? Books need metaphors. Important. Figure it out later.

“Of course not,” I said. “I’d never make fun of the Dells.”

Chapter 1: April

Needless to say, I was probably going to make fun of the Dells.

I’d never written a book. But I’d read enough year-of memoirs to think I had a handle on the general formula. Identify a quest, design a stunt with predetermined rules, adhere to those rules while executing the stunt, encounter obstacles, overcome obstacles, and in the end find yourself staring at a sunset—happy, enriched, and clutching tight to your breast a semi-contrived tale worth sharing. It all seemed so simple. It was a genre where blindly bumbling ahead was celebrated.

Which is not to say I ever thought the act of becoming a guard at Sing-Sing, or reading the Encyclopedia Britannica, or even spending a year cooking your way through Mastering the Art of French Cooking was easy per se. But it had to be easier than this. I spent weeks sweating my early-May departure date. Waiting for call-backs. Staring at my silent phone. Made innumerable trips from Madison to the Dells to sit through meetings like the one I’d had with Dan, begging for a minimum-wage job typically given to 18-year-olds sight unseen.

It’s not like I was planning to spend my summer shuffling through a Paris breadline. I was going to “The Warterpark Capital of the World!”

As the protagonist, I even hit all the right notes. I had recently lost my job. My personal life was generally adrift. And I had history with the Dells. The plan was to work at eight different attractions for two weeks at a time, all while being decades older than my coworkers—every moment practically lacquered with potential occasions for self-deprecation and redemption.

It’s not like I was planning to spend my summer shuffling through a Paris breadline. I was going to “The Warterpark Capital of the World!”

For the Dells, it’s the upper Midwest’s Las Vegas-cum-Branson. It almost makes fun of itself. The Dells comprises a combined city and village with roughly 5,000 permanent residents catering to over three million interlopers who visit each year and spend more than one billion dollars at the cities’ waterparks, funhouses, and go-kart tracks. Every road is choked with billboards and garish signage. It’s a playground fueled by adults acting like children, chaperoned primarily by a seasonal workforce of children acting like adults.

So I ignored any doubts and focused on the endgame: readings, signings, glowing reviews. At minimum, I’d immerse myself in the Dells. “Discover” that an unhealthy reliance on fun and superficiality was holding me back from Things That Matter. It would be enough. It would have to be. And if it wasn’t, like the horse metaphor, I could always figure out the important parts later.

Chapter 2: May

On my first full day in the Dells, I fell off a duck.

The day began with Dan Gavinski dropping me off in the middle of a vast lot enclosed by tin-roofed stalls housing OWD’s fleet of tourist troop carriers. My training partner, Tommy, was new, but he had a week’s head start. As such, he taught me how to twist my foot sideways to balance on the metal beast’s half-inch ribs to climb inside—no ladders or stairs to be seen.

Ducks are intimidating: They’re 32-foot-long land-sea vehicles first used for amphibious assaults. For the tours, they’ve been refitted with a vinyl canopy protecting the passengers. They weigh seven tons and have both wheels and a propeller.

Tommy scampered ahead of me to the driver’s cockpit with a powerful, easy grace. It had rained earlier that morning, so I slipped on the slick steel and fell, cracking my knee on the on the way down. My knee was throbbing, but I couldn’t help but smile. Five minutes into my first job and I’d already had a pratfall? Maybe this book thing would be easy.

“Second thing you want to do—after not falling off—is to remember to put in your plugs. They drain the bilge at the end of the day. It’s a boat with holes, otherwise.” Tommy was standing on the hood of Java Sea, eyeing the loose plugs as he reached to give me his hand.

A boat with holes … Chapter title? Subhead? Book title? If nothing, apt metaphor.

Tommy lifted the hood and explained how to check a duck’s oil and water levels. Back in the cockpit, he ran through the shifting pattern. How to turn a duck on—there’s a starter on the floor next to the gas pedal, no key. He pointed out some condensation-licked gauges.

When Tommy turned his back, I pulled out my pen and notebook, began scribbling: Tommy—19, white-blond dusting of stubble on chin. Hockey player. Trainee like me. Achingly earnest. Never been kicked in the head. He thinks anything is possible. Poor Tommy. Stick by Tommy. Grizzled cynic v. doe-eyed naïf. Dichotomy = good. Potential for conflict!!!

“I go to Central Michigan,” he said. We had a few minutes before our trainer arrived. “Business. Hope to be a CEO or CFO someday. You?”

“Tough major, the CEO track,” I said. I cut off my giggles when I realized he wasn’t joking. “I’m a writer, I guess. Someday I hope to be George Plimpton.”

Why am I so goddamn happy? So at peace? Because I’m driving seven tons of badass? Makes no sense. Feels safe here. May be Stockholm syndrome.

Tommy shrugged. I looked to the gray sky and thanked the universe for providing me the perfect foil.

For the next week and a half, we grabbed Java Sea each morning, fattened her up with gas and oil, and spent six hours taking driving lessons. The trainer rode shotgun while Tommy and I alternated one hour behind the wheel, one hour off. Each night I returned to my motel, a squalid hovel appointed with all of the finest amenities from the ’70s. My shoulders and back throbbed from wrestling with seven tons of war machine, my face crimson with windburn. Exhausted, I settled in to transcribe my day’s notes before collapsing into sleep. Then I did it again the next day.

After 10 days, I reread my diary and began tallying the usable scenes and potential characters. But when I came across my first-day sketch of Tommy, I wondered who’d written it.

My entire post-collegiate working life had been devoted to advertising and writing—two worlds cluttered with colossal egos and cutthroat jealousies. You became conditioned to flinch in anticipation of a shank. But here it was different. Everyone I came into contact with—Tommy, our trainers, any of the other 50-some drivers—wanted me to succeed. They asked about the book, told me it sounded cool. They loved their job and didn’t much care about mine. Whereas, I was used to spending the majority of my waking hours being protective and envious of anyone passing through my orbit.

May 10, 2010: Fitting in is way too easy. All I have to do is say fuck all the time, tell a few dick jokes, and take a chew every so often. Have they forgotten I’m writing about them?

May 14, 2012: Why am I so goddamn happy? So at peace? Because I’m driving seven tons of badass? Makes no sense. Feels safe here. May be Stockholm syndrome. Mine this.

Before my stunt-mandated weeks at OWD were up, I asked Dan if I could come back and drive tours on my off-days the rest of the summer. I’d convinced myself I needed more time to do additional research, gather more stories for my OWD chapter. In reality, I knew I’d miss my new friends and didn’t want to leave them.

“For free, if you want,” I said.

Dan laughed. “Shit, yes. And of course we’ll pay you. You’re welcome here anytime.”

When he turned, I pumped my fist.

Chapter 3: June

My right hand was still waiting for a shake when Allen took off sprinting. He was surprisingly nimble for 83.

“Hey, hey, hey, hey!” he yelled, as he bounded across the sprawling Circus World campus. A group of kids was crawling on an ancient circus railcar. The flatbed was sun-beaten, faded red with white letters drop-shadowed in blue: “Gollmar Bros. Enormous New Show.” Behind them, the Baraboo River floated quietly past, cutting through a complex of modern brick museums, old animal barns, and big top performance tents.

“You can’t be on here!” Allen yelled. “It’s dangerous.” The kids startled, quickly regrouped as they hopped down, pigtails and shoelaces flapping. Running past Allen, one screamed for cotton candy.

Allen adjusted his trucker’s hat, its thick white foam panel indented from the weight of three Circus World pins. “The kids don’t listen. They just don’t listen. And the people that run this place don’t know their own fanny.” He stabbed a finger at my chest. “You can quote me on that. Where’s the ‘Keep Off’ sign? Where’s the sign for the Tiger Show?”

I shrugged. He pointed past the Hippodrome. Sunlight reflected off the metal dome on the covered oval.

“Over there?” I said.

“Yeah, exactly. The Tiger Show is around the corner and no one can see it, that’s where. Paint arrows on the ground for all I care. Something.”

A woman walked up pushing a stroller. Allen calmed as he bent over and spun the mobile hanging above her child.

“Ready for the circus?” Allen asked, addressing the baby.

“We sure are!” the woman replied. “We just need to know where the Tiger Show is.”

Allen straightened and turned his back. “Bah,” he said, his arms landing on his hips. He began to walk away and yelled back: “You tell her.”

During my two weeks in June at Circus World, days went more or less like this: In the morning, my volunteer coworkers and I smiled weakly and shuffled around a dying attraction. Allen and I pointed folks to their seats in the empty Hippodrome. (“Anywhere you can find one! Ha ha.”) Virgil and I told fish stories next to the carousel. If it was a particularly slow day, Brian, the animal trainer, might yell at me for taking pictures of the elephants, then I’d go lean against a tent pole, chastened and killing time, and eat my allotment of free popcorn.

Every day I worked in the Dells, the place pushed back. I flinched at overheard Circus World cracks—the popcorn sucks? Maybe you suck. From the looks of you, you should probably consider some roughage anyway.

Circus World opened in 1959 on the site of the Ringling Bros. Circus’s winter quarters. Many of the original buildings dated back to the 1890s. Over 100 years later, Circus World housed the world’s largest collection of circus memorabilia, including hundreds of refurbished wagons, some worth over $500,000. But those wagons didn’t move, and the memorabilia sat in glass cases, and none of it whirred or blinked or sprayed water in your face. Circus World had been slowly withering since its mid-’90s heyday, the turnstile numbers down over 60 percent. It didn’t take a trained eye to notice all the peeling paint.

June 4, 2010: There’s a sadness here. Circus World is wheezing. It’s infecting me. I feel guilty I have no pep, can’t even fake a smile half the time. Why do I care? Book-wise, isn’t this exactly what I want?

There was a time I adored the Dells. As a kid, it was my Mecca. Pilgrimages were carefully plotted with campground research and clipped coupons and schedules crafted to balance the waterslide and go-kart time. At some point, though, I decided it was beneath me. An embarrassment to my beloved home state of Wisconsin.

But every day I worked in the Dells, the place pushed back. I flinched at overheard Circus World cracks—the popcorn sucks? Maybe you suck. From the looks of you, you should probably consider some roughage anyway.

Circus World was mostly tedium, though I was able to watch a mini-circus perform every day. Even at an hour, it clipped along with tight performances from fire jugglers, acrobats, an aerialist, elephants, and tigers. I had the opportunity to talk shop with a professional circus clown. Stand 20 feet away from a woman spinning from the rafters by her ankle. Strut with Al Ringling’s cane tucked under my arm while carrying trapeze wire used by The Flying Wallendas.

It would have been disingenuous to say I truly understood Circus World—but there was a dissonant weightiness that pervaded the empty grounds. At one time, circuses mattered. For many Americans, a circus provided their first exposure to electricity, motion pictures, recorded sound. My daily tasks were boring, but I didn’t hate them. I knew work-hate and this wasn’t even close.

June 11, 2010: Two days left here. No one will want to read a melancholy love letter. Where’s your goddamn arc? Your vitriol? Need more color, edge. Stick by Allen. Yes. He’s full of piss and profanity. Maybe he can do some of the heavy lifting for you.

I invited Allen to lunch—hot dogs and Cokes. While we ate, Dave SaLaoutas, the performance director and ringmaster, stopped by to say hello. He was dressed in his ringmaster outfit, top hat in hand. His mustache, full and perfect.

“Dave, you know Jason?” Allen said. “He’s going to write an important book. Bestseller. The Today Show and everything. Probably.”

I’d already talked with Dave numerous times and he’d answered my questions with passion and kindness. Dave was born in Alf T. Ringling’s home. In 30-plus years at Circus World, he’d worked in concessions and as an assistant to the director before making ringmaster. For the past 20, after every show, he’d strip off his tails and top hat, down to a white T-shirt, and mop the Hippodrome.

“I have, he’s a good guy. Now quit socializing and get back to work,” Dave joked, before wandering off. He was whistling.

Allen’s eyes followed. “I told Dave we need new signs. I tell everyone we need signs. How much does a damn sign cost? We need lots of stuff. I’m fed up.”

“Dave seems nice.”

“He’s the best. A great, great man. Everyone who’s still around cares so much. There’s nothing he can do.” Allen took a bite. “There’s nothing anyone can do with no money. Maybe if your book sells a million copies, people will read about it and come back.”

I picked at my bun. “Maybe.”

Chapter 4: July

Dieter Tasso had a refrain in his stage act: “You like it? I do it again.” Tasso’s act was part juggling, part one-liners, all vaudevillian deadpan. Sometimes he dropped his balls and saucers. Sometimes the top hats he flipped up with his feet didn’t land on his bald head. But it was hard to tell when the miscues were for effect, or simply the effects of age; by that point Dieter was 78 years old, recently yanked out of retirement. But when his hats and saucers found their intended marks, he always said it: “You like it? I do it again.” Then he did again.

I watched Dieter’s show every night for two weeks while working at the Tommy Bartlett Waterski and Thrill Show, a half-ski, half-variety stage show directly across the street from my motel, on the shores of Lake Delton. Dieter wasn’t edgy or groundbreaking or anti-comedy—just undeniably funny.

Everyone talked about Dieter, loved Dieter, knew his life story. But I wanted to go deeper—to hear the tales of his childhood in Berlin, his work in Paris and Las Vegas, of being brought to America by the Ringlings in the ’50s. What it’s like to juggle for a living for over 60 years, piecing together a career as a traveling performer. And I’d also have to ask him why he was back in the Dells, out of retirement to submit to the crowds. I avoided him until I couldn’t any longer.

“People think I walk around with my head down because I’m sad,” he said when we finally met, as he led me to a picnic table. “But it’s all the damn dogs. Like a minefield around here.” He pointed at a pile of dog turds.

We talked for almost an hour between the afternoon and evening shows. The late July air was a wool blanket. Dieter’s voice was warm, stripped of its performance edge. He told me how he used to perform his act on a wire. “No joke,” he said. “And no jokes.” He added the comedy after his body began to break down. He’d worked on and off in the Dells for 30 years and told me he’d lived a “beautiful, wonderful life.” How lucky he was to have been paid to see the world, to have the opportunity to climb on stage every night.

“So why are you here again?” I said. “I’d heard you retired.” Dieter’s body, normally taut and lithe, slackened. As soon as I asked the question, I wanted it back.

“My wife passed in January,” he said, barely a whisper. “I was sitting in Sarasota and the roof was falling on my head. I missed her so much. So I called Tom Diehl, you know, the owner, and asked him if I could come. He told me the show was booked, the budget spent, but that I should get in my car. He’d find money and I was welcome in the show anytime. Two days later I was here.”

He went on to explain he’d turned down a job in Germany. He didn’t have to tell me it was because the Dells and Tommy Bartlett’s felt like family at a time when he most needed a family. I’d experienced the same thing during my days at OWD. I found it again at every job after. I found it everywhere I went.

Every two weeks, I’d start a new job knowing no one, like on the first day of school. I’d wallow in an attempt to turn my new coworkers into caricatures. Then they’d surprise, often move me. By the time I sat down with Dieter, I was worn out trying to shoehorn real people and real stories into what I thought my memoir required.

But I wanted the book. I collected interviews, hours upon hours of digital files. I transcribed my notes every day, the file inching near 300 single-spaced pages. And maybe Dieter had wanted to talk about his wife’s death. Maybe it was cathartic. But I’d already known what he was going to say—the story had made the rounds. Just as I had known exactly how my book was going to end before I ever started.

That night, something snapped. I was invited to an employees’ party in the trailer park. I stayed out until dawn, because, why not? I didn’t think about my book or what any of it meant. I didn’t take any notes except for one barely legible scrawl: I’m fucking drunk and feel truly fucking alive for the first time this summer. Dieter changed his act, why can’t you? Fuck the book. Do something different tomorrow. Today. Whenever. Fuck you.

Chapter 5: September

“Is this anyone’s first time on a duck tour?” I raised my hand, prompting my riders. Half of the 20 or so tourists followed my lead, their heads bobbing.

“Oh, good,” I said. “Me too.” They laughed. They always laughed.

For roughly the two-hundredth time since May I faced a tour group and told them about emergency exits. “Out the back and anywhere you don’t see a green metal bar.” Then I slammed the duck into gear and punched the ignition. The engine shuddered and stumbled before catching with a roar. And just like that we were off, barreling toward the trees.

By September, there were no more stories to be gathered, no more nosedives to induce. Tommy had returned to college, as had most of the drivers. Those who were left were Dells lifers, or people who hadn’t quite figured out how to leave the nest.

For much of the summer, I’d been “that writer guy.” In a tiny, insular community like the Dells everyone knew who I was, even when I didn’t. Now, all I wanted was to be one of them.

I wanted the book. And maybe Dieter had wanted to talk about his wife’s death. But I’d already known what he was going to say—the story had made the rounds. Just as I had known exactly how my book was going to end before I ever started.

Over the next hour we trekked into the Wisconsin River, over County Highway A, splashed down in Lake Delton, and cruised back into the woods. I told duck stories and answered questions in my well-oiled patter. My jokes were corny, and I loved every one. I’d even borrowed a few from Dieter.

As we made the loop and rolled down the same trail on which we began, Mt. Olympus rose in front of us across Dells Parkway. The roller coasters, the bizarre mash-up of faux Roman and Greek ruins, the Trojan horse again. Four months ago, I had pictured this moment as the book’s closing scene. It was a perfect allegory—for where I’d been, where I was going. The river, the journey. That damn horse.

Now I wondered if there was any way my book could exist if I stripped out the artifice, if my initial intentions were put to bed and it became an authentic story of a region and its people. Wouldn’t that be better?

This would be my last group, my last day. I pulled into the dock and unloaded. I made eye contact and thanked every rider for joining me. I parked my duck, pulled my plugs, and saluted my boat-with-holes. I said my goodbyes while telling my coworkers I’d be back soon to visit. I drove to the motel, packed up my room, and headed north.

Sept. 15, 2010: Hard to face whatever’s next. I’m exhausted and burned out and wholly fulfilled. But I’m worried as soon as I leave this will all be gone. The feeling, everything. I have to get it right.

On my way out of town, I drove past the Trojan horse just as I had every day that summer. Sometimes a three-story Trojan horse with a go-kart track disappearing into its gut is a majestic eyesore symbolizing everything we shouldn’t be or want. But sometimes it can be beautiful, too.

A Year Later

Almost a year to the day I left the Dells, I returned to attend the wedding of a duck driver. Everyone I wanted to see again would be there. It was held at Chula Vista, one of the Dells’ mega-resorts. As I drove past the golf course, the outdoor waterpark, the villas, nothing felt ostentatious or overblown.

My book didn’t sell. As the rejections rolled in throughout the previous spring, my agent was apologetic but firm. “Sometimes this happens,” she said. “It’s hard to know the exact reasons.” I was left to wonder. Maybe the East Coast provincials didn’t want to take a chance on a book set in that wasteland between New York and L.A. Maybe I didn’t gather enough whiz-bang stories, the kind that sell books. Maybe I didn’t write them well enough.

All I knew is that I couldn’t write it the way I had planned. I still produced a stunt memoir, but the edges were rough, the contrast fuzzy. I couldn’t pretend I discovered something all of these people had been living their entire lives. The Dells was absurd, but so was I—I owed it to myself and the Dells and everyone who invited me into their homes to tell the truth. So I wrote a story about how I loved what I saw right from the beginning and for whatever reason, it loved me back.

At the wedding, with the Wisconsin River just outside the windows, I visited with old friends. I told them I was living in St. Paul and married now. People peppered me with variations on “How’s the book coming?” I didn’t know what to say, so I gave vague answers bordering on lies. When I tired of talking, I danced.

The evening eventually turned boozy. Late in the night I sat at a round table, sweaty and out of breath, surrounded. The lights on the dance floor pulsed in time with the music. Conversations stalled. One driver asked a question, and then around the horn they went.

“C’mon, are you done yet?”

“Yeah, when can I buy it?”

“Am I in it? I’d better be in it.”

“What about the ducks? You talk about driving the ducks?”

“What about that one time…?”

The truth was, the book was buried. The smallest, last-chance publisher had been queried months before. It was never going to sell. My first instinct was to soft-shoe, to give them what they wanted to hear. After all, they wouldn’t remember.

“I’m still trying to figure it all out,” I said. “I’m still working on it.”

It was the most honest story I could tell.