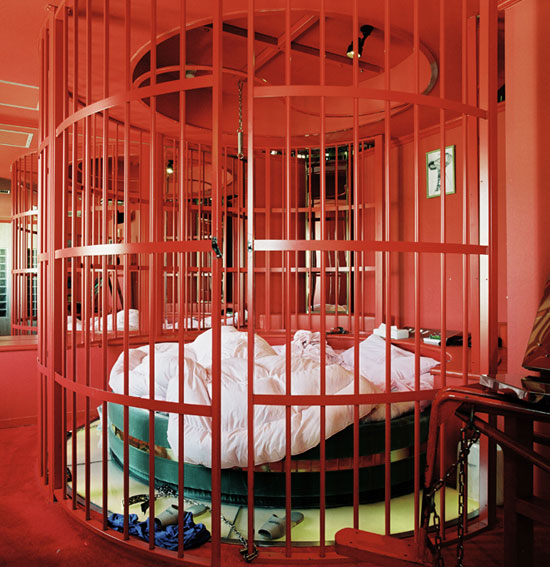

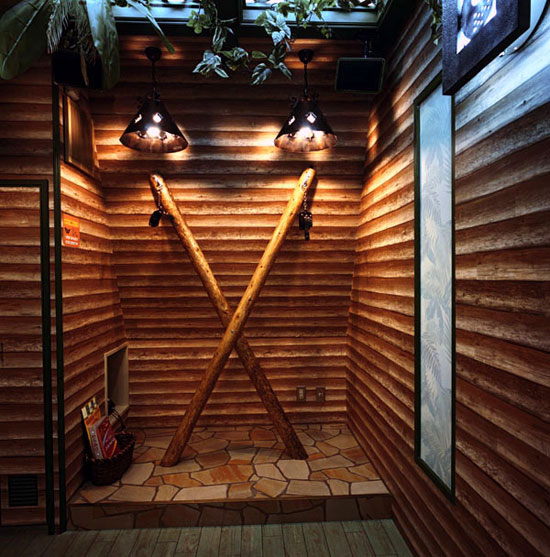

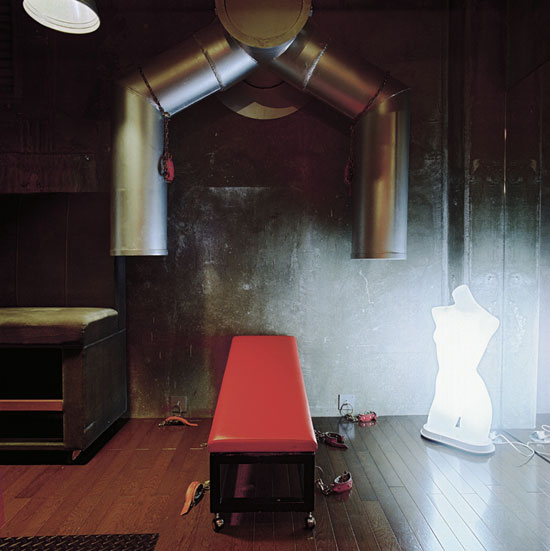

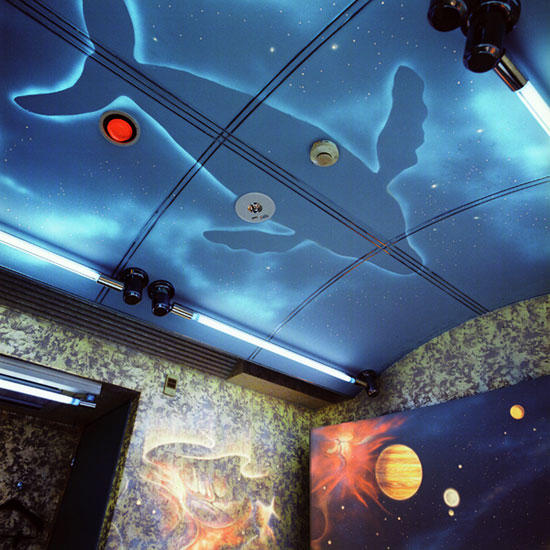

Unlike the dank motels where Americans allegedly seek anonymous sex, Japan’s love hotels are playful and unapologetically sexual. Photographer Misty Keasler shows the humor, desire, and even the loneliness of these empty rooms.

Misty Keasler studied photography at Columbia College and graduated with a BA in spring of 2001. She contributes to Harpers, the New York Times, the London Daily Telegraph Magazine, Time, Dwell, Esquire, and Newsweek among others. She was awarded the 2003 Lange-Taylor Prize, included in PDN’s 30 Emerging Photographers and the book 25 Under 25 Up and coming American Photographers. Her first monograph, Love Hotels, from Chronicle Books will be followed by a show of the same title at the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College, Jenkins Johnson Gallery New York, and Photographs Do Not Bend Dallas at the beginning of 2007. Her work is included in the permanent collections of the Museum of Fine Art, Houston, The Kiyosato Museum of Photographic Art, Japan, and the Dallas Museum of Art. Her first camera was a Polaroid given to her on her 7th birthday.

How did you learn about these hotels?

In 2003 I accepted a job teaching at a public school in Japan and lived there for eight months. After reading about the phenomenon of wildly decorated love hotels in my Lonely Planet, I looked for them all over the place but didn’t see any. I had no idea they were everywhere and that I walked near many on a regular basis. I just didn’t know what to look for from the street. I finally got bold enough, toward the end of my stay, to walk into what I though was a love hotel. And this series began.

Why were you drawn to photograph them?

While I was living there, I was interested in being absorbed into Japanese culture—hence the job as a public servant. I wanted to photographically study some aspect of life and culture there and I am drawn to offbeat topics. Love hotels were a perfect fit. The photographs became a study of public and private space (the rooms are simultaneously both) and a study of romance within modern Japan.

How did you get into the hotels to shoot the rooms? Did you rent them?

I actually never paid for a room, or used one myself. In the beginning I tried to talk my way into rooms by myself, but my horrible Japanese proved insufficient for anything more than ordering sushi. I had two phenomenal translators that could have sweet-talked us into the Pentagon to take photographs. These guys were great. They explained what I was doing and asked if I could shoot any really interesting rooms in the hotels. I was turned away from many hotels but also met some great owners and managers who allowed me access to their hotels, and even to the diaries left in rooms. There are several pages of these in the book from Chronicle.

Who goes to the hotels? Are they primarily fueled by the sex trade?

The most common misconception people have when seeing these images is that they are brothels, but in order to rent a room you must come in as a couple. There are 30,000 to 40,000 love hotels in Japan and they are used by just about every sort of couple. I think there is a huge range [of people] that frequent love hotels—young unmarried couples who live with their families until they get married, married couples who may live in very tight quarters with family, couples in extramarital affairs, and prostitutes with their customers.

Why is there so much anonymity when visiting love hotels?

I am sure that in part it is because some of the amorous liaisons that occur in the hotels are of a secretive nature. But there are some larger [inferences] that can be made about the hotels. I can’t help but think it must be indicative of the prevailing cultural attitudes about relationships and sex. Privacy is a much higher priority in one’s personal life [in Japan] and sex is not an integrated part of daily life.

What’s your favorite room?

The Hello Kitty S&M room has to be my favorite because it is so unexpected, and I love the colors in the prints of that room. But the Gulliver’s Travels room is quite wild and bizarre—everything feels cartoony and funny. I love that room.

Why do you think the Hello Kitty S&M room is appealing to hotel guests?

Hello Kitty is really big in Japan. Many women there are drawn not only to very cute, almost little-girl-ish toys, but to also being very cute and innocent. I think the room would probably appeal to a girl’s [interest in] cuteness, and the S&M part of the room [appeals] to a man’s more sexual interests. Though, I think most Japanese girls probably giggle when they see the cuffs-and-bondage Kitty. In our culture cute and innocent aren’t generally mixed with the supersexual, so the room takes on some extra irony.

You’ve done quite a bit of documentary photography around the world. What, if anything, distinguishes the Love Hotels project from your work in the Guatemala City dump or Russian orphanages?

I think there is a similar vision that runs through all three bodies of work, not just visually, but in [that they’re] work about cultural institutions made by the same artist. However, since the love hotels are photographs of a comparably decadent, luxurious part of life in a developed country, they are very rich in color and devoid of people. In some ways, this more lighthearted work is a bit colder than the other bodies of work you mentioned. While the rooms were fun and funny, sometimes they felt quite empty and, ironically, devoid of love. In contrast, I fell completely in love with the subjects found in the garbage dump and orphanage photographs, and in love with their lives. I think a deep compassion and intimacy bleeds through in those images that is absent in the love hotels.

Yes, the fact that there were no people in Love Hotels caught my attention. While this makes sense, how does this emptiness distinguish the Love Hotels project?

All these photographs are ripe with implications. I think of them as being very pregnant. Since the rooms imply their own utilitarian function, I believe they ask the viewer to be active. It is difficult to see the rooms without imagining the people who use them or [without the rooms becoming] implemented in one’s own fantasies. These pictures would have been so different with people in them and in many ways less interesting.

How has the audience response to this work differed from the response to your Guatemala City dump photographs or your photographs of Russian orphanages?

While both are studies of public and private space, the subject matter is so completely different. Both responses are positive, but I think Love Hotels requires less emotionally from the audience and doesn’t ask for too much introspection. It is a much more lighthearted body of photographs.

Are you a documentarian or an artist? Do either of these words fit, or is there a definition that’s more appropriate?

I think I am both, and probably a few other things, too. I used to really worry about how I got labeled, but now I let critics and writers and curators pound it out for me. I still work in old processes and am very connected to each step involved in making prints. I do almost everything with my own hands and that connects me more to the work. I feel I am very much a part of an art community and conversation, and I pray that my work moves people and starts conversations or makes people upset—which is what art is supposed to do. The one label I don’t generally apply to myself is that of “photojournalist,” though some days I do pretend I am one.