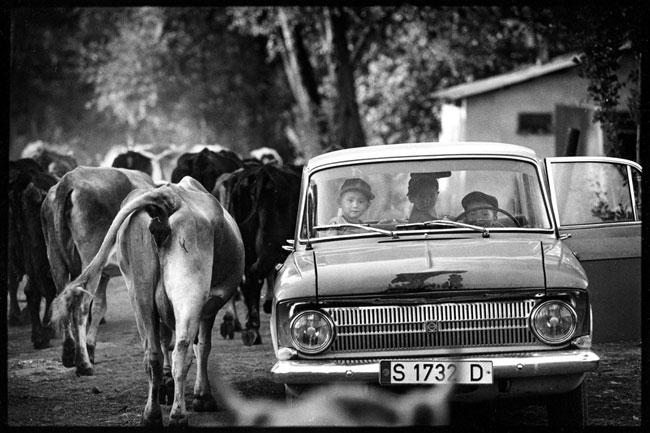

Tim Dirven was born in 1968 in Turnhout, Belgium. He studied photography at the Saint Lucas Institute in Brussels from 1988 till 1992. His studies in Belgium were followed by a specialization year in documentary photography at the FAMU-Institute (Academy of Performing Art) in Prague. He made his first reports with family friend Willy Kuypers during his studies in Romania and former Yugoslavia. In 1994 Tim Dirven started working as a freelance photographer and since 1996 he has been working full time for the Belgian newspaper De Morgen. He lives in Brussels and makes daily reports of Belgian news items.

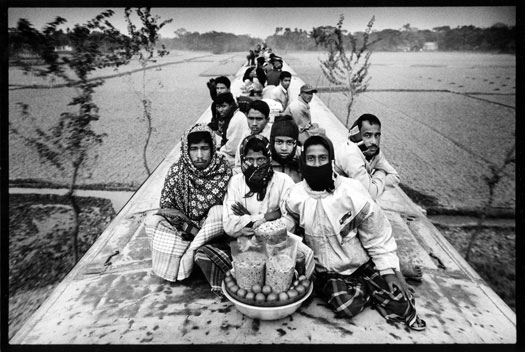

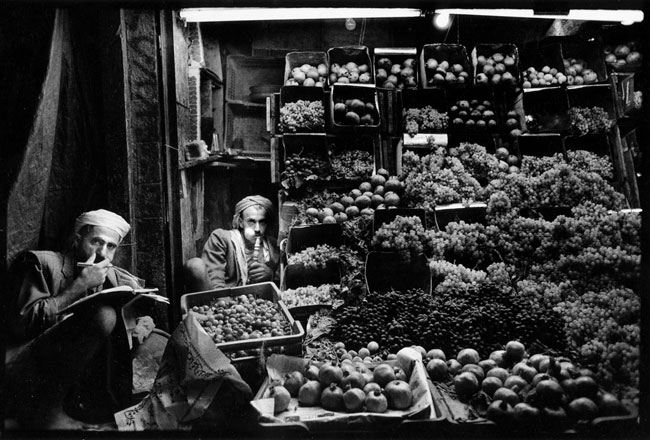

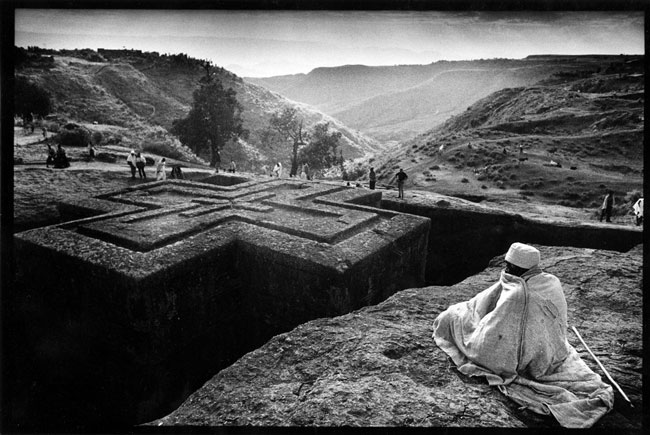

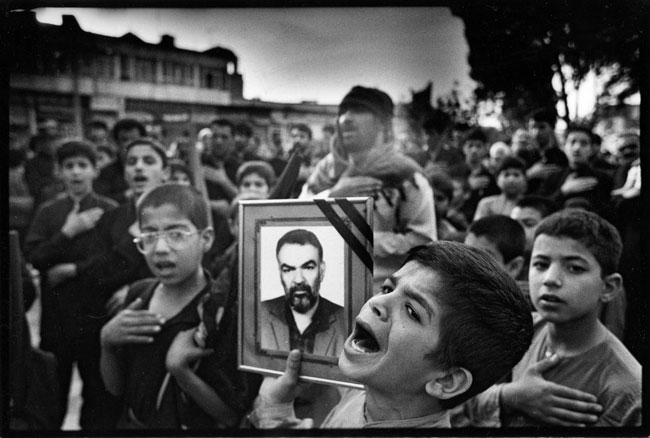

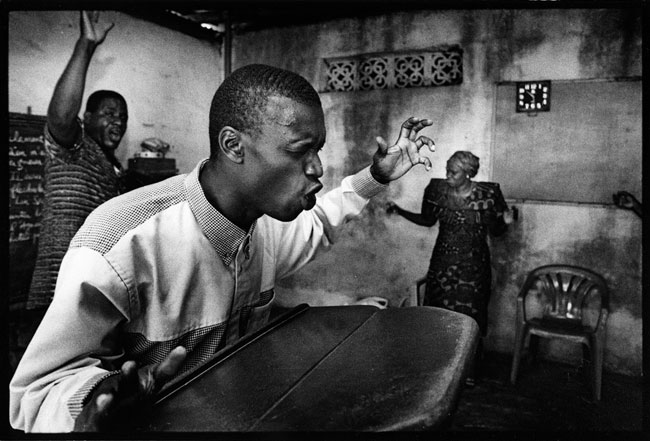

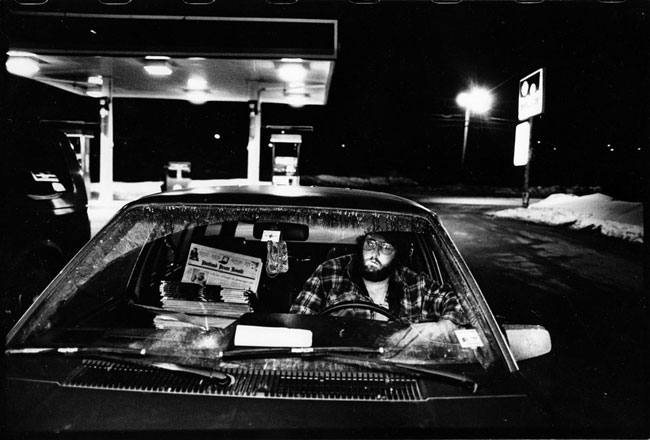

Dirven’s pictures don’t blur the line between art and journalism—they eliminate it. His camera finds intimacy in the well-worn or far-away news story. On the pages of De Morgen and the walls of the Antwerp Fotomuseum, these photographs bring the most distant lives closer.

The photographs in this gallery are compiled in Dirven's upcoming book Yesterday’s People, published by the FotoMuseum Provincie Antwerpen.

What obstacles have you faced while photographing in politically contentious locations?

I was in Turkmenistan, on my way to an assignment for MSF [Medecins Sans Frontieres] in Afghanistan. Because of the difficult relationship with the government, I was forbidden to take pictures there. As a photojournalist, this was a very hard punishment, but it was the only possibility to get into Afghanistan.

Do you ever experience ethical difficulties when photographing in contentious locations or circumstances?

Most of the time, I feel sympathy for the subjects I photograph. But, sometimes I am not able to stay neutral. When I report on the extreme right in Belgium, the portraits I make of their politicians are never very flattering.

I don’t want to show horrible facts in my pictures. I’d rather show emotion than shock people with atrocities. Because of this, I want total control over the selection of my pictures.

What are photographs unable to convey or express?

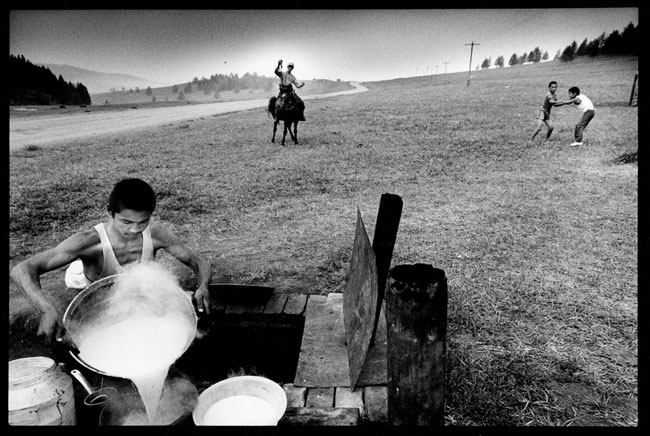

Photographs are visual expressions. Pictures miss the sound and smell of the real moment. The foul smell in the psychiatric hospital of Gheja in Romania was very dominant, but it is totally absent from the pictures. During the horse races in Mongolia the earth rocked and you could hear the stamping horses from miles away.

As a contributor at De Morgen, how do your photographs enhance the news reports that they accompany?

[De Morgen’s] photographers are seen as photojournalists whose work is of equal value as that of the journalists. When we work on a news report, our picture is a second opinion, and it sometimes gives background information or our own interpretation.

What kind of control do you have over where you travel to shoot?

Half of my travels are of my own initiative. Half of my time abroad, I am on assignment.

What is the difference between having your work shown at the Fotomuseum and having it published in newspapers?

My work in De Morgen is published every day and is [therefore] fragmented into small pieces. The exhibition (at the Fotomuseum) gives an overview of my work during the past 10 years. [The photographs in De Morgen are] small prints with grainy structure in the paper, as opposed to the large high-definition prints in the museum.

Are you a journalist?

I feel myself to be a journalist and as a craftsman, almost never an artist. During my work at the newspaper, I am a journalist; this is my job. During reports, I feel like a documentary photographer; this is my passion, and is the reason why I started studying photography in the first place. While I am printing in my darkroom, especially when printing on baryth paper, I feel like a craftsman of an endangered craft.