The Oxford Project

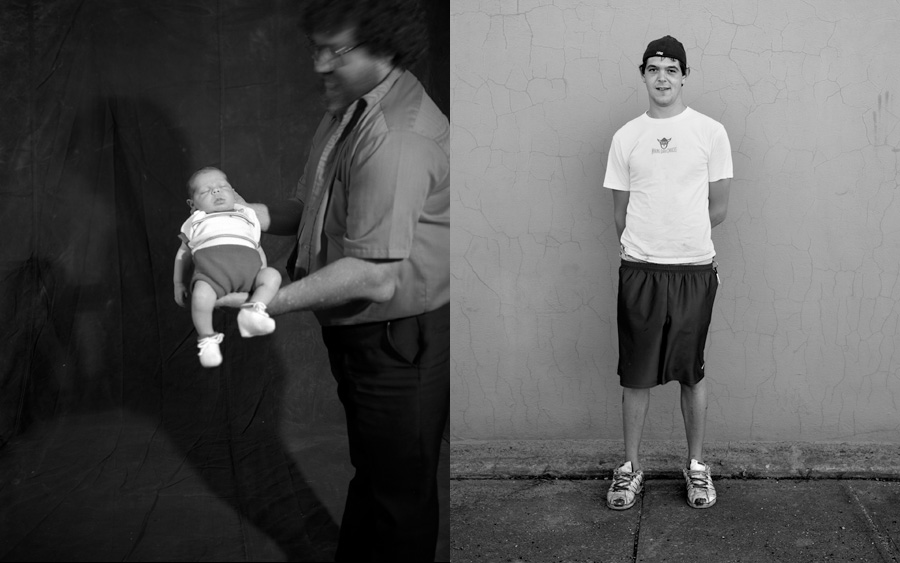

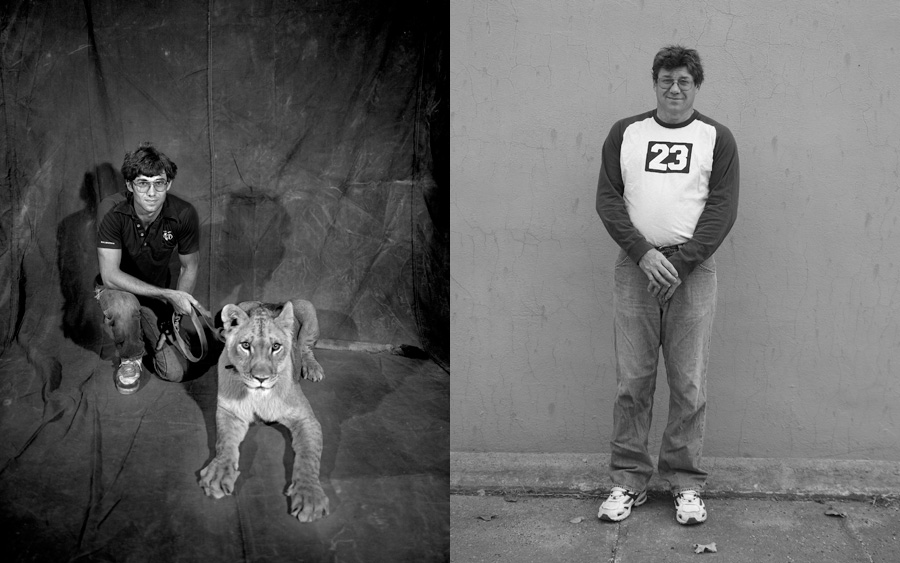

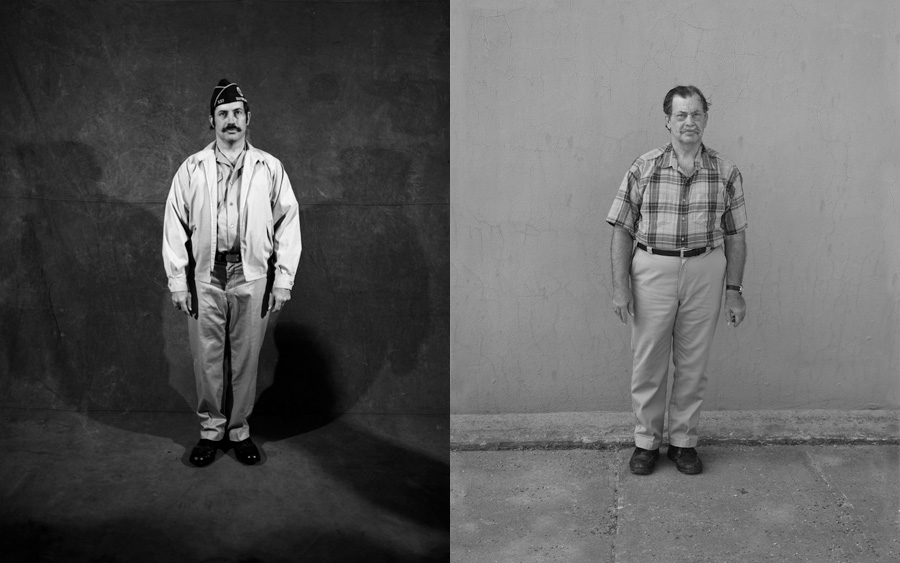

In 1984, photographer Peter Feldstein announced that he wanted to take free portraits of everyone in Oxford, Iowa (pop. 673). Twenty-one years later, he went back.

Interview with Peter Feldstein and Stephen Bloom by Rosecrans Baldwin

Peter, how did the project begin? Why did you choose Oxford?

Feldstein: I’ve lived in Oxford since 1978. One May morning in 1984, I walked up and down every street in Oxford, slipping flyers under some doors and taping flyers to other doors, inviting residents to have their photographs taken. I taped the sign to a storefront window on Oxford’s main street. Inside, I covered the windows with aluminum foil and brown-wrapping paper, hung a construction tarp as a backdrop, and turned on two quartz lights.

That first day no one showed up. Over the next several days, my only takers were kids on their way home from school. A retired couple stopped by, and I snapped their pictures. Several more people poked their heads in the storefront. On Memorial Day, Al Scheetz, on his way to march in the American Legion Post parade, stopped by and I took his photograph. Later, Al brought with him four dozen Legionnaires and their families. The project took off from there. By late summer, I had photographed 670 Oxford residents. Continue reading ↓

The Oxford Project (Welcome Books) is the remarkable portrait of a small town. All images copyright © the authors, courtesy Welcome Books, all rights reserved.

Ben Stoker: When I was 10, my dad died. He had renal failure. He used to take me to his office on Saturdays, and in the afternoon we’d catch a Kernels game. Pretty much I think about my dad every day. I remember feeling his beard against my face. I remember his hands—they were soft and warm. Two years ago when I was 19, my mother died of cancer. She was my guiding light. I was very angry with God. He came and took my father and then he took the other person I loved most in the world. I’d be a liar if I said everything is all right. I know I’ll spend an eternity with both my parents. Two sayings come back to me: “He’s not going to put you through something you can’t handle,” and “What doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger.” A lot of people don’t like small towns because they’re so tight-knit. But that’s what makes this place so great. You know who’s sleeping with whom, but when your mother dies, you also know there’ll be 28 people at your door with casseroles.

Brianne Leckness: My mom left me at a church when I was three. She used to travel with the carnival, and the carnival ended up going broke in Iowa. When my mom and my stepfather had a hard day, they’d take it out on me. So she left me at this church with our dog Freddy. She pinned a note to my shirt that said, “Please take care of her. We can’t any longer.” On my 18th birthday, my mother blew into town. She wanted us to go on The Montel Williams Show and say how she really never wanted to give me up. She asked me to move in with her in Florida and start a new life. That didn’t work out, so I came back to Des Moines, where I’ve been for six years. I met a guy from Honduras and he didn’t speak a lick of English. I got pregnant, then we broke up. After that, I really got into partying. I’d stay out till three or four in the morning. I liked drinking. I met another guy at a bar, and I got pregnant again. Now I live with the fathers of both my children and another guy. Nothing for me has been normal, so why should now be normal?

Calvin Colony: I’m a plumber, but I’m also a diver for the county. I dive for drowning victims, hunting accidents, snowmobiles that go through the ice. It’s black down there and you’re crawling through logs. I’ve probably pulled out 20 bodies since ‘73. I’ve had maybe 13 lions over the years. You can train ‘em, but you can never tame ‘em. You can’t trust ‘em around children. They’re like cats around mice. They’ll kill a dog pretty quick. I used to feed ‘em road-kill deer. For the last six years, I’ve been going to a resort in Jamaica called Hedonism. On one beach, you have to have your bottoms on. On the other beach, you can’t lay out unless you’re naked. You’ll see people having sex if you stay around long enough. All the alcohol you want is included in the price. It’s a good time. You don’t have to take many clothes.

Hunter Tandy: Two months ago, I moved to Ida Grove to run a remodel and repair shop. That’s what I’ll probably be doing in 10 or 20 years. When I was a kid, I said I’d like to be buried in an 18-wheeler when I died. I still do. I always wanted to be a truck driver like my father. Ashton Kutcher is my second cousin. Ashton and his wife Demi Moore came and visited me 16 or 18 days ago. They surprised me. Ashton called and asked where I was living and then they just showed up. They stayed at the Super 8. Ashton and I played a round of golf, and she stayed at the motel. When we got back, we all sat around and shot the shit. Demi is pretty cool. She’s really levelheaded, a real nice person. I told Ashton, “You are one lucky son of a bitch!”

Jim Hoyt, Jr.: I got drafted in August 1970. Our job was to plant anti-personnel mines outside the perimeter. We’d carry M203 grenade launchers. We’d go on search-and-destroy missions. You’d have to watch for booby traps. I never had to kill anyone the whole time I was over there. I saw The Bob Hope Show, some of the Gold Diggers, and Martha Raye. They had Donut Dollies at the base. They were nice, friendly women from the States. For R&R I went to Bangkok—they sure named that place right. I came back and started doing bodywork. I seemed to be good at filling dents. But three months after I started, I came down with malaria. It’s like the flu, but worse. You start sweating, then you get the chills. It attacks your brain. I’m a porter at JCPenney. I pick up trash, pick up hangers from the customer service area, clean up the restroom, clean the doors and mirrors. There are a lot of smudges. I like to go target hunting now. It’s something you don’t have to feel too bad about.

Jim Hoyt, Sr.: My father worked for the railroad and my mother was a rural schoolteacher. I went from kindergarten through 12th grade in the same building. My biggest achievement was winning the Johnson County Spelling Bee in 1939. I was in the eighth grade and I still remember the word I spelled correctly: archive. After basic training I was sent overseas and went through the Battle of the Bulge. I’m the last living of the first four American soldiers who liberated Buchenwald concentration camp. There were thousands of bodies piled high. I saw hearts that had been taken from live people in medical experiments. They said a wife of one of the SS officers—they called her the Bitch of Buchenwald—saw a tattoo she liked on the arm of a prisoner, and had the skin made into a lampshade. I saw that. I received the Bronze Star, but when I got home, I didn’t have a job. I worked at a bank, then for Burroughs Adding Machine, then in construction. I ended up a rural mail carrier. For the 50-year anniversary of the liberation of Buchenwald, they asked me to return. They would’ve paid for the whole works. But I said no. I didn’t want to bring back those memories. Thinking back, I would have pushed to be a psychologist—if for no other reason than to understand myself better.

Pat Henkelman: I get up at five a.m. My son—he works as a prison guard—stops by for breakfast every morning. He usually wants Cream of Wheat or oatmeal. Then I say my morning prayers, take a bath, and eat breakfast. After that, I clean houses. I come home and have lunch, usually a sandwich and a cup of green tea. I watch TV, usually CNN. Sometimes I take a nap. In 1940, Harry and I were working at a bee factory in Harlan, and when I came back from lunch one day, he was filling my jars. That night we met at the county fair and had our picture taken, and that was that. In 1985, after 45 years of marriage, he left me for another woman. I didn’t know who the woman was, but everyone else in town did. I would have felt better if she was young and beautiful, but she wasn’t. They used to play euchre at the Legion Hall. My faith helped me get through. I don’t have malice or anger. You have to forgive. For a while I thought I hated him. But that stopped. Jesus died to suffer for our sins, but you’re still responsible for the sins you commit. I think the instant you die, you step out of your body. You have to be perfect to go to heaven—like Mother Teresa—but almost everyone else goes to purgatory. There used to be a hat store in town. I wish it still was here. I love hats.

Interview continued

Stephen, how did you get involved?

Bloom: Until a couple of years ago, Peter taught at the University of Iowa, where I still teach. After taking several photographs in 2005 of the same people whose images he captured in 1984, Peter suggested that I ask Oxford people to tell their stories, to reveal how their lives had changed in the intervening years.

Do any of the subjects particularly stand out in your minds?

Bloom: Actually, every one of the 100 people we interviewed had a compelling story to tell. Each was different, but each was dramatic and heartfelt.

What surprised you during the photo and interview sessions?

Bloom: We learned Oxford residents’ views on God, the hereafter, the war in Iraq, the food they like, their hobbies, idols, daily routines. We learned of individual acts of heroism—some great, some small. We witnessed awkward children mature into secure, confident parents.

Feldstein: Most people are shorter, taller or heavier today than they were when I first photographed them. Some are now stooped. Several cannot walk or breathe unassisted. At least four farmers have lost fingers, hands, or limbs.

Visually, almost everyone posed in an identical manner despite the more than two-decade interval. Mary Ann Carter, co-owner of the local Ford dealership, still tilted her head to the left, her hands cupped neatly at her side. Retired carpenter Jim Jiras still wore a seed cap, and still had two pens in his shirt pocket. Brothers Tim and Mike Hennes stood exactly the same as they had 21 years earlier.

What did you learn from the Oxford project about the fate of small towns in America?

Bloom: Everyone wants to talk and few people want to listen. If you give people the opportunity, and you’re sincere about listening carefully, most people will unburden themselves by telling you what’s on their minds. In a sense, we acted as confessors. My interest was to give voice to people whose voices are usually ignored.

Much of small-town America has disappeared, and what already hasn’t, will in the next decade or so. These self-contained, insular places in America’s “fly-over country” are virtually untouched by both the vitality and vulgarity of urban America. The Oxford Project allows us to peak into a world soon to disappear.

What are you working on now?

Bloom: I’ve just finished a book, a nonfiction global mystery story about pearls, entitled Tears of Mermaids, which will be published next fall by St. Martin’s Press.

Feldstein: I’m working on a photographic commission for a large public building.