The Dead

Inspired by photographs of Sicilian catacombs, Jack Burman has spent over a decade scouring Europe and South America, among other places, for the dead. (Some images may be disturbing to some viewers.)

Interview by Nozlee Samadzadeh

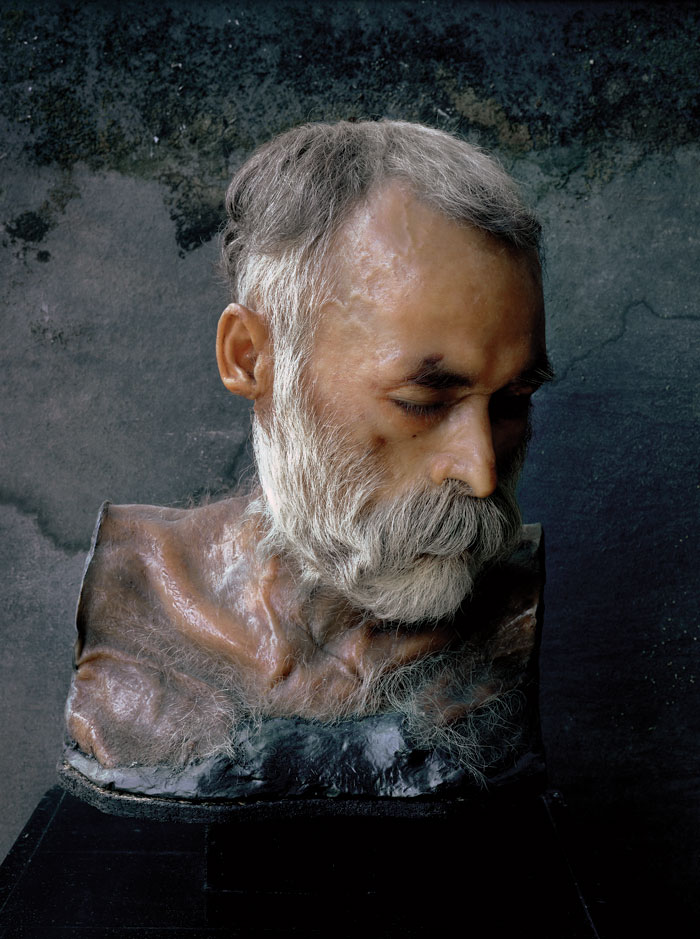

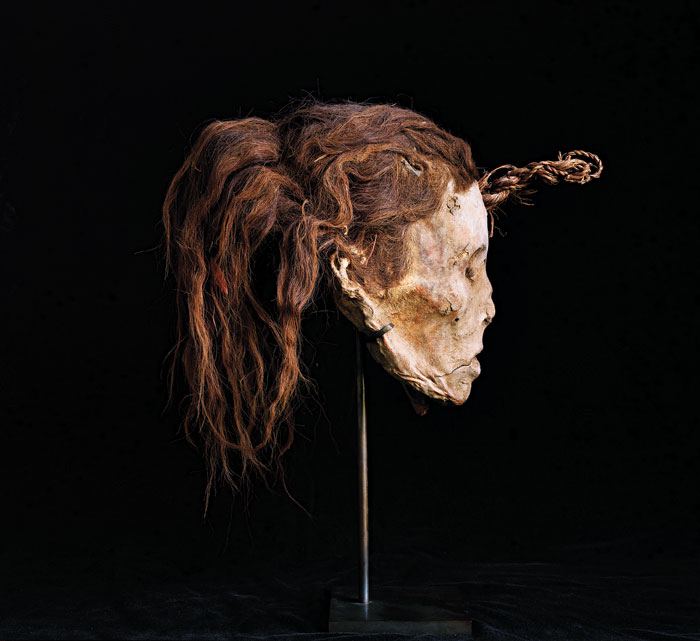

Shooting alone, with only natural light and a long-format camera, Burman develops his photos in Edward Burtynsky’s labs to capture his subject in pristine, oversized detail. The preserved faces, hands, and bodies he seeks out are half anatomy lesson and half a reminder of our humanity: These scientific specimens and skeletons were once alive, just like us. Read the interview ↓

All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Artist interview

How did you decide to photograph the dead?

With slowness. As time passed. As I learned to know what it took to breathe through the work I did. Yeah, there were influences, duly named and thanked in the afterword and text to my book. But it had to do with going where I needed to see clearly in the lowest (at times, dream-wise) possible light.

What is the process behind getting permission for a photo shoot?

Long, slow, patient. Eased somewhat in these times by the tools of cyberspace. Reliant on the right good, gracious people—sometimes many, occasionally just one.

What message do you hope to convey with your photography?

Some of the truth of the body. The strength of damage and loss. The hardness and motions of time as laid on and under the skin. The feel.

Are your photos meant to elicit thought about the meaning of death?

I’d say no. At least, they don’t do it in me.

How do you feel when viewers are viscerally “grossed out?”

Briefly content in some sense, but a limited one. I don’t hear of that many people backing away for this reason, only the occasional one. I think it serves me only as a minor—very minor—register of the prints’ clarity.

The men and women in your portraits likely did not have say in how their bodies would be treated after death. Is it fair of you to further exploit them by displaying their photographs?

Let’s try on “exploit.” My dictionary says “utilize (person etc.) for one’s own ends, esp. derog[atory].”

I utilize them for my own ends—after anatomists have extensively utilized them for theirs, which include vital learning and instruction, yes—as well as, in some cases, which I think are understandable and unavoidable, academic career advancement. And my ends? They are as I said to breathe through the work I do and place before others, some of whom find clarity and worth in the prints. I make no profit—ever, in any material form—from this work. Strictly then? I “utilize…” in the way the dictionary said.

Should the dead retain a right to privacy?

We all have a right to and need for privacy. At times the need is met; at times not. When I enter their privacy it is with slow, hard respect for their hands, arms, shoulders, and eyes. The very few who take my prints (or book) into their hands and rooms—those I know of—see with the same discipline.

The faces of the dead can be difficult to look at, but the body parts you photograph are fascinating and almost painterly or fake-looking. How do you interact with, say, a preserved hand over a preserved face?

“Over?” It doesn’t feel that way. Remember the girl’s hair at the start of Garcia Marquez’s Of Love and Other Demons? The hair is the girl’s years, eyes, body. Thus each hand and face.

How will your body be buried when you die?

Buried? Maybe. If so, real plain.

Where else do you plan to look for photo subjects, i.e., preserved dead bodies?

Where I’ve looked for maybe 25 years: far from North America as a rule (but not inviolably); Catholic countries; places of damage and hard truth; places of a kind of strong science.

What are you working on now?

I always liked the idea of votive offerings. Nice word, votive—in fulfillment of a vow.