When did you realize that your father had something special in his portraits?

Stefan Nadelman:It was around the time I was graduating college, when I fully realized what my father had accomplished. I majored in Fine Art, so I imagine the prospect of my future career along with my roots helped focus my attention to this wonderful thing [his photos—ed.] that was in clear sight my whole life. I knew something needed to be done with the collection, but it would be another six or so years until I revisited it.

TMN:What was your father’s background with photography?

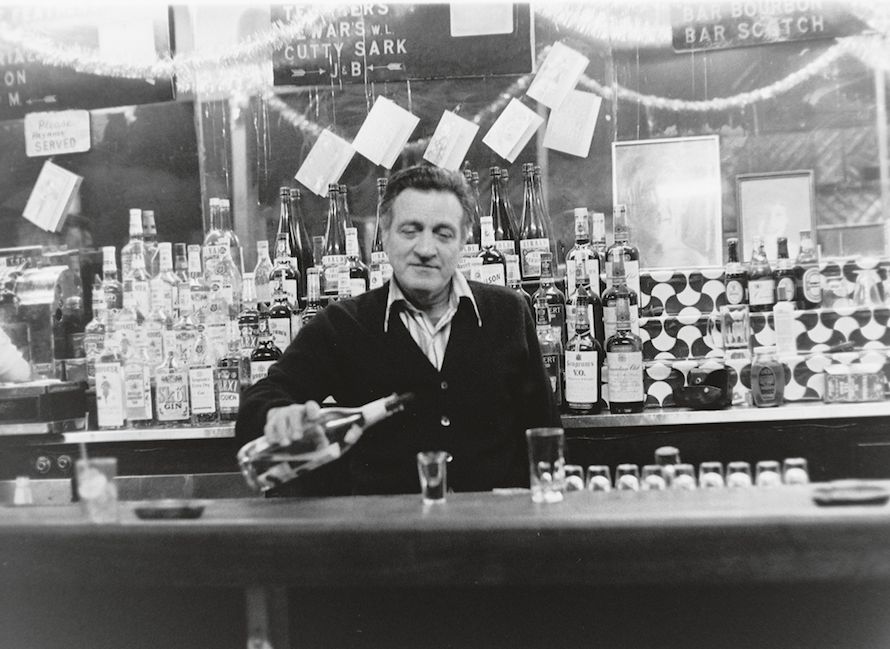

SN:I’m not sure if my father would have gotten into photography on his own. A friend and coworker at the Village Squire Clothier in the late ’60s sold him a brand-new Pentax for a song. At the time, it wasn’t a dream for him to take pictures. He wasn’t in the market for a camera, it was just a good deal. He had no training in photography, and he just wanted to learn how to develop film and make a print. So he took a brief photography course and learned what kind of film he needed to use, how to set the light meter, that was the extent of his training. The rest of his photography career was based on his own trial, error, and discovery.

TMN:What do you think makes his style unique?

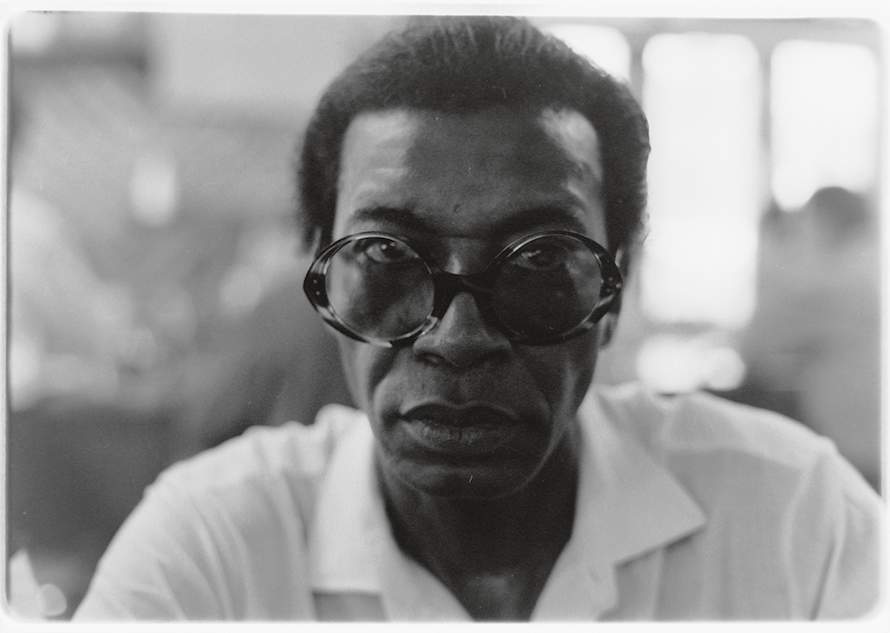

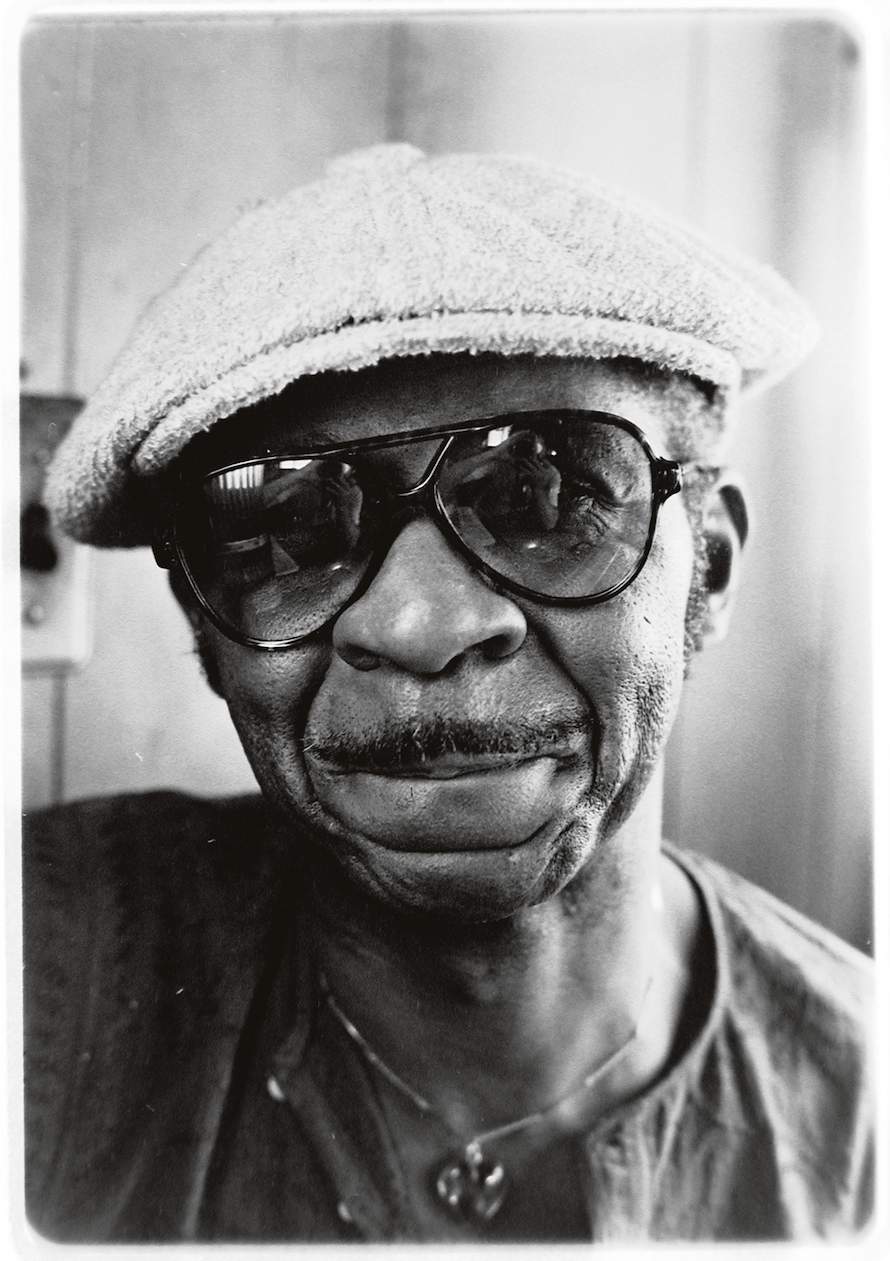

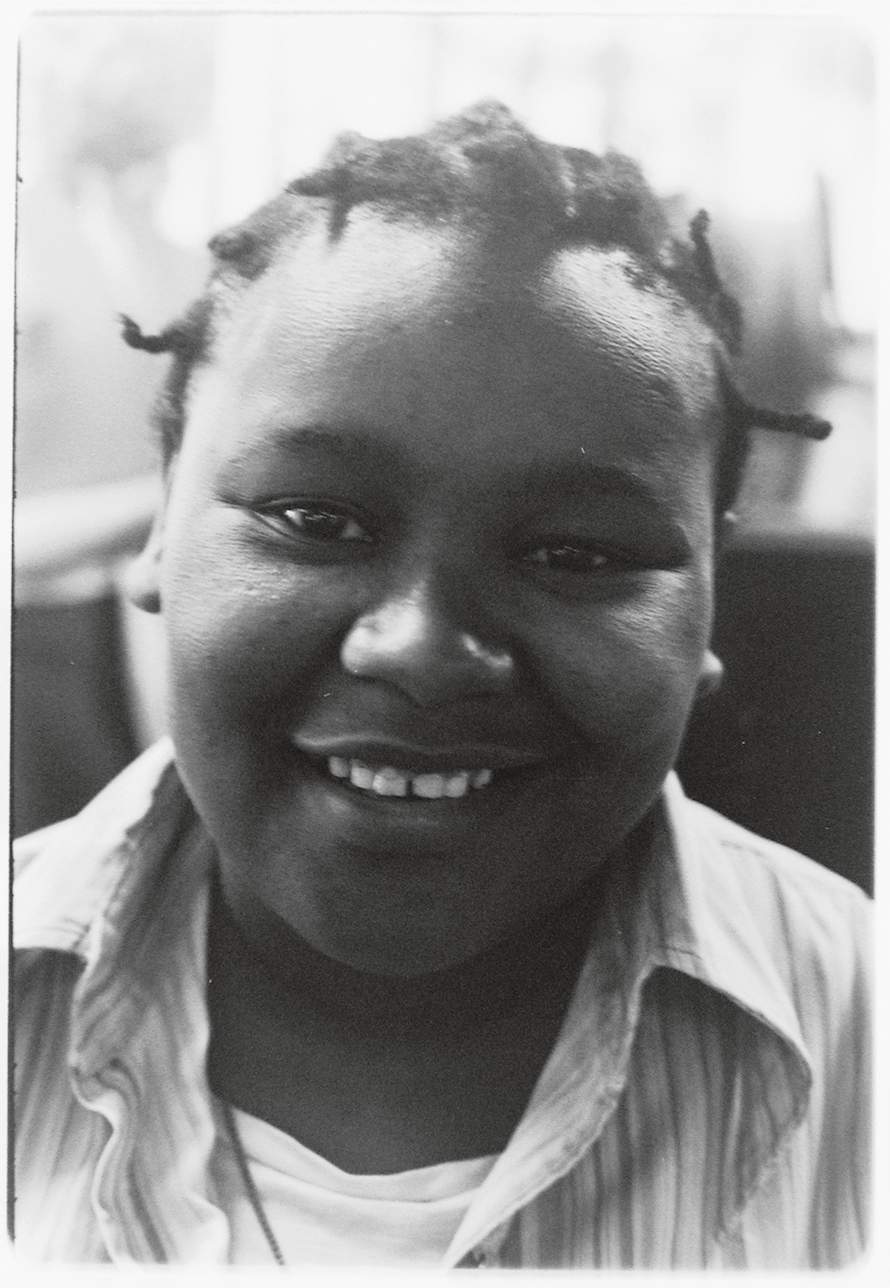

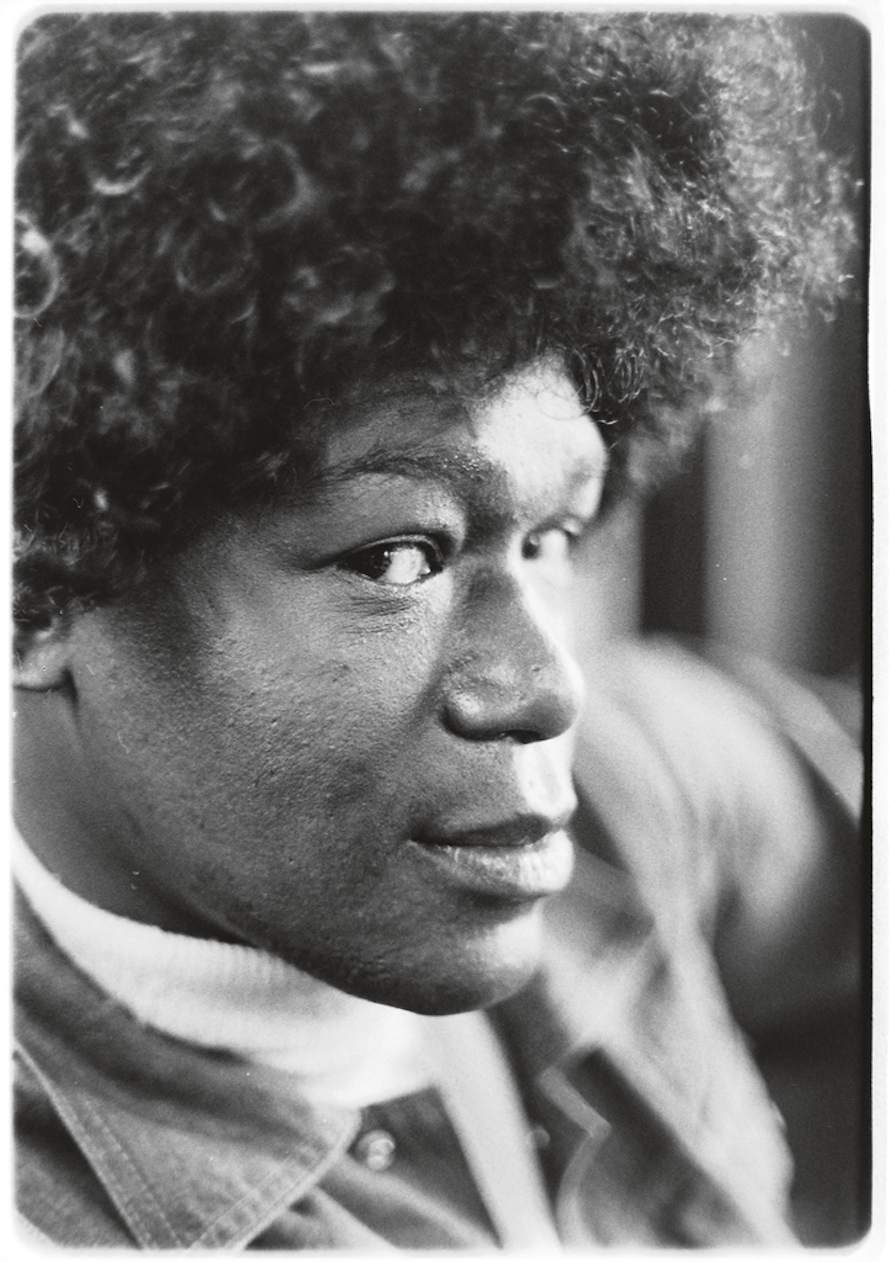

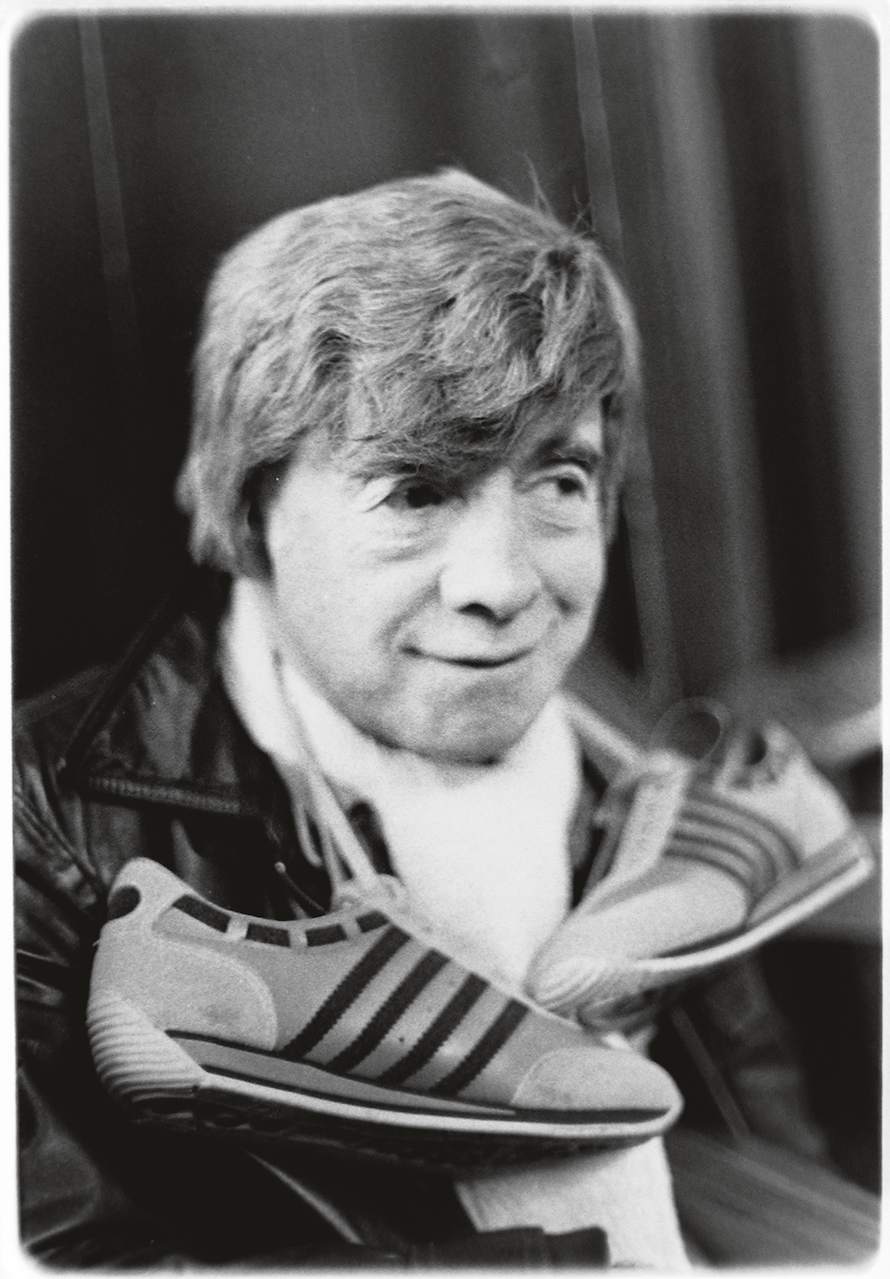

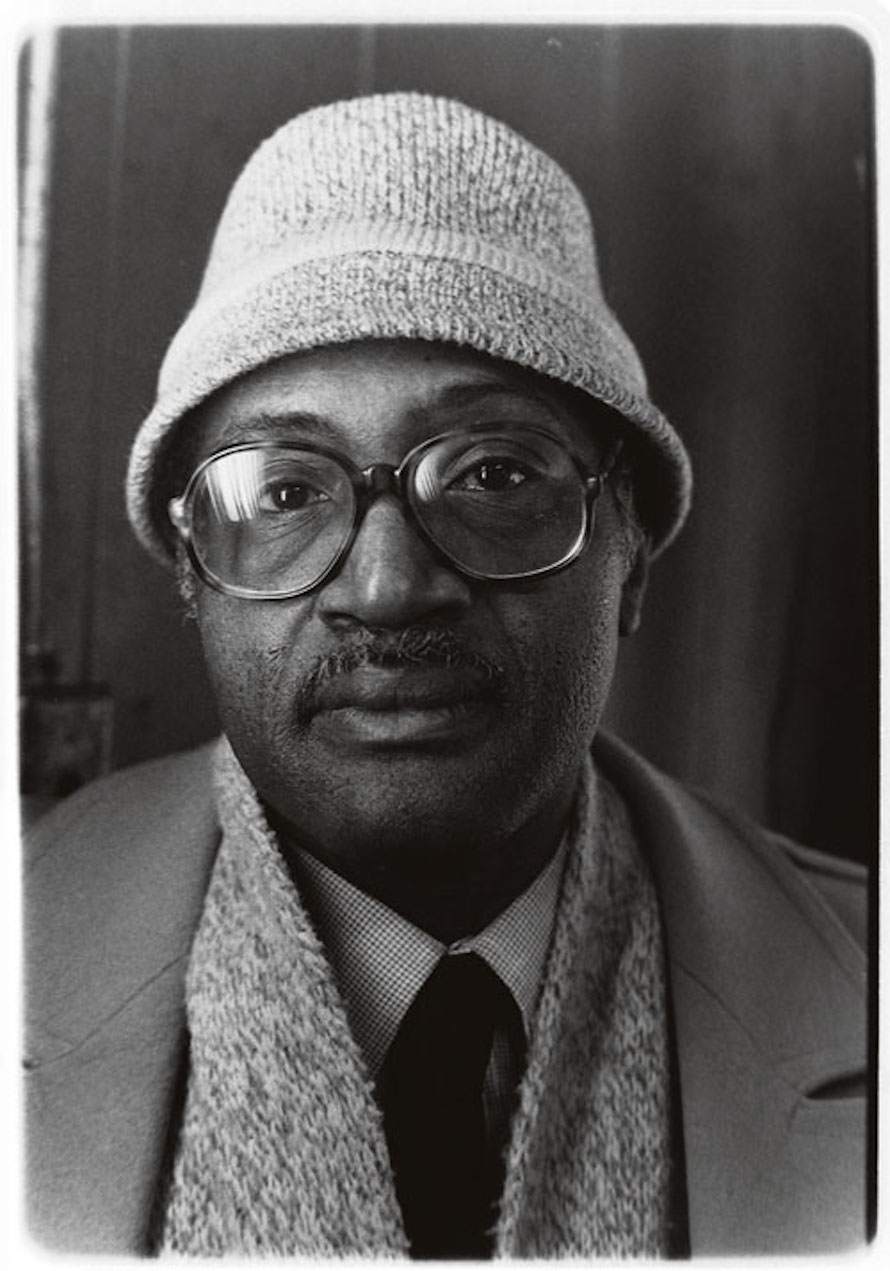

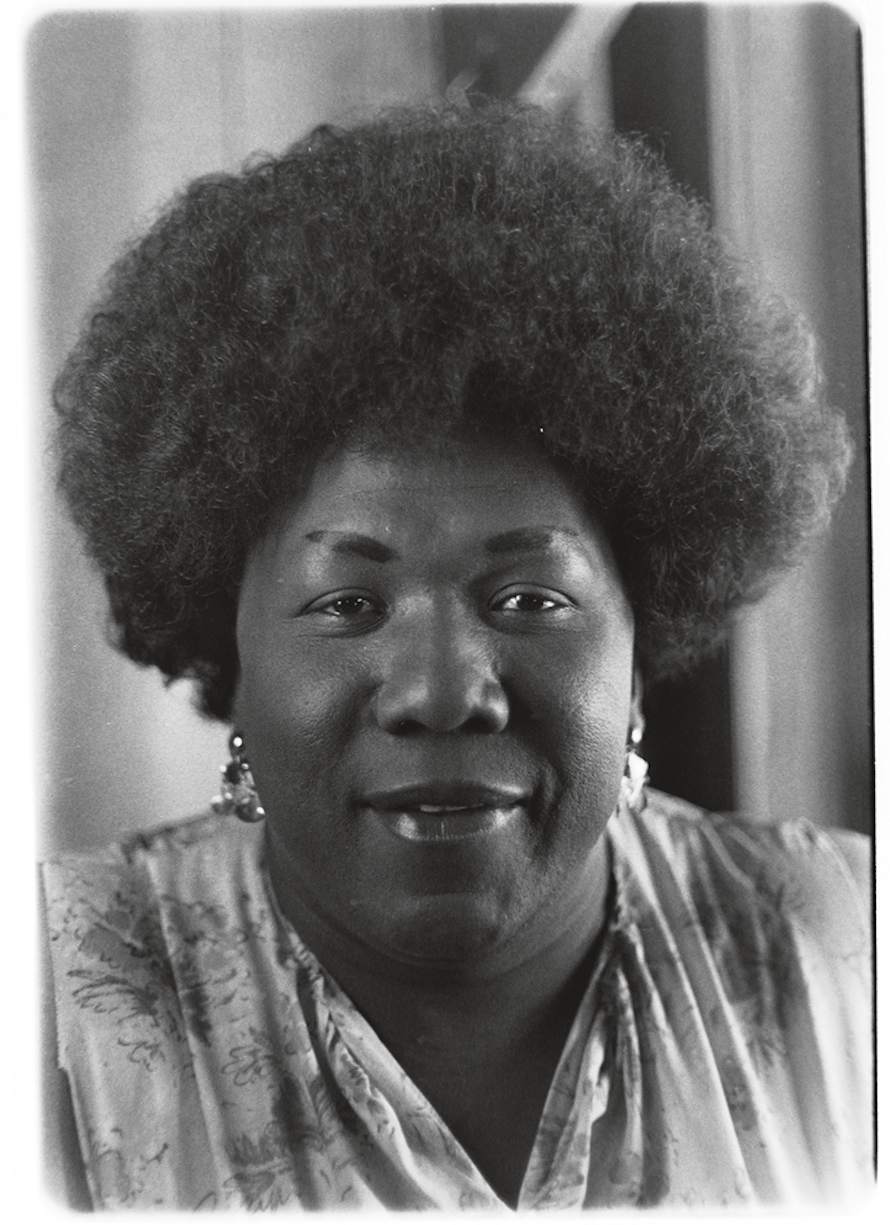

SN:I wouldn’t call his photographic style unique, but I would call his persistence and consistence unique. He used available light, so he didn’t always get the cleanest shots. But his work remains unique because of the sheer volume and the staggering array of faces. My father chose subjects that he says were interesting. To us modern-day folk, everyone in 1970s New York City is going to be interesting. But I think he took into account the subject’s dress, demeanor, and countenance, and if any or all of these qualities interested my father, they were a potential portrait.

TMN:So do you see his personality in what he captured? In the subjects he was drawn to?

SN:My father photographed every and all type of personality and class. From the meek schoolteacher to the hardened wino. But now that I think about it, if you spend 10 years in a bar, there’s no doubt a person will take away qualities, good and bad, from such a prolonged experience. My father’s anecdotes and way of speech are quite colorful, and I believe a part of his personality contains bits and pieces from the Terminal Bar.

Looking at all the portraits, my father seemed to be drawn to a lot of flamboyant and flashy types, along with the downtrodden. Both these categories are polar opposites but are charged with emotion.

But he seemed to be interested in the state of the state as it were. He was concerned with people sleeping on the sidewalks and people destroying themselves with drink. In a way, he wanted to “put it on paper” for posterity, so people would know what was going on there. He was, and still is, a staunch opponent to alcohol.

TMN:You say in the introduction to the book that without photography, your father wouldn’t have survived the Terminal Bar.

SN:I wouldn’t call my father a people person. He has a short temper. Those who know him would laugh at the idea of Shelly, or “Sheldoom,” being in the service industry. So the only way my father would persist having to interface with customers of a bar, located across from a transportation hub, was if he had some way to cope, or something he could get out of it besides a paycheck. Otherwise, he would have quit at the very moment someone pissed him off. It took him three months to realize the potential his position could have for his burgeoning interest in photography, and he decided to embrace it.

TMN:Your documentary, The Terminal Bar, showed at Sundance. How did your dad react?

SN:He was supportive the whole way. It was as if he was passing the Terminal Bar torch to me. He wasn’t taking all those pictures just so they could sit in a binder somewhere in New Jersey; he knew (or hoped) someday there would be an audience. When he saw the film he was so happy. I believe he truly appreciates the way I approached it his material. My parents play the film all the time for friends. He claims he still never knows what happens next, which I find interesting.