In an art world filled with bright lights that quickly fade, Marilyn Minter’s work, although jaw-droppingly sensational, radiates endurance. Minter renders our flaws fashionable and makes glamour dirty. She talks with The Morning News about her slow and steady climb up the art world ladder, shooting for Versace, and what her work has in common with The Wire.

Marilyn Minter was born in 1948 in Shreveport, La. Minter lives and works in New York. Her current exhibition at Salon 94 will be up through January 20, 2007. All images are copyright © Marilyn Minter and appear courtesy of Salon 94. All rights reserved.

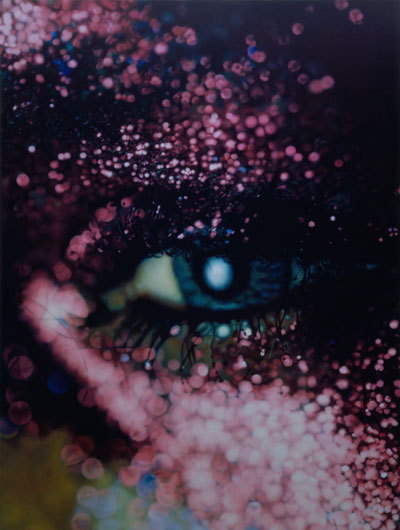

I love images like “Glazed” because I get the feeling that, if you had photographed an eye like this from farther away in a different light or with a different treatment, it would be indistinguishable from a photograph in a magazine or advertisement. Why have you magnified this eye?[The painting] shows glamour gone awry. But it’s also representing a real thing. It [depicts] the instant in a magazine that gives us so much pleasure. We know we’re never gonna look like that and the models aren’t even gonna look like that. I haven’t invented any of the tropes in my images. They’re all already there and I have my own interpretation.

But people believe at some level that beauty in magazines and advertisements is attainable.

It’s an ideal that we strive for. But there’s constant failure. Your shoes are going to get dirty; your hem is going to come undone; you’re going to start sweating. I do a little commercial photography. Every model I’ve met doesn’t really know how beautiful they are—they just know what people tell them. I’ve seen some of the most beautiful people in the world sneak on makeup, thinking I won’t see it. There is no escape.

Are you undermining all the effort people put into making fashion and beauty photographs seem perfect?

I’ve tried to make an image of what it feels like to look. How can I make judgments of things that give people so much pleasure? I don’t have a moral judgment. I love looking at fashion. At the same time, I know my relationship to it is really complicated. I don’t think fashion is superficial; it helps you to identify your tribe.

I’ve heard the word “glamour” used often to explain what you’re addressing or challenging, but is this accurate? Are you addressing glamour in our culture?

Holland Cotter coined the term “pathology of glamour” [to describe my work]. I don’t know what the issue is. I usually leave it to writers to define the issue. Someone will say a good phrase and I’ll start using it. Words and phrases aren’t my language.

Sometimes it looks as though your models are choking on necklaces or about to fall in their high heels. Is there a destructiveness or violence in your work?

There’s no violence at all. It’s just that I’m much more fascinated by the ungroomed than the airbrushed. I remember seeing a Matthew Barney video of someone messing with a pimple, and I was fascinated. I think that grooming rituals are a part of our biology. I mean, isn’t it great to pluck your eyebrows?

Do you see the images in your work as beautiful?

I think things like this are beautiful in their complications. I’m intrigued by the complications. I think they’re delicious. I’m stunned when people say, “That’s disgusting.” I’m like, how can you say that?

So the work reflects your personal idea of beauty?

It’s definitely my vision and it’s totally subjective. It has been underscored so many times that anyone in the “real” fashion world is appalled by what I like.

Really? How is it that you have ended up doing fashion shoots and advertising?

Well, they use the blandest examples [of my work]. That photo, “Glazed,” that you like so much is a picture of a blue-eyed African model. [Fashion editors] didn’t even want to look at that. They reject every piece of work I love. Now, I don’t even take a job unless I get to do what I want.

So, you did art first and then more commercial work.

Usually people do commercial work and then decide that they want to make art. For me it was the opposite. My work in fashion started after [I was already] making these images. I was approached by an editor to do a Versace campaign with Devon Aoki. I don’t even know anything about fashion. I’ve never even photographed a whole human being.

During the Whitney Biennial, billboards of your work could be seen over Manhattan streets. How did these billboards happen to go up?

I’ve always wanted to make the billboards. And Creative Time said “sure.” I was disappointed because we could only get the cheapest billboards. So we had to really Photoshop my images. But, someday I’m going to get something that will fit the size of a negative.

People are very responsive to your work right now. Is it because of the times, or has your work changed in some way?

People have been paying attention to me for the past five years, to be fair. Art history is loaded down with artists who no one paid attention to or only paid attention to when they were young. I think it’s a combination of the best work I have made hitting the zeitgeist. It’s also taken me a long time to be able to communicate. I’m making my best work now.

What is it about the zeitgeist makes your work so appealing?

It would be easy to say I’m ahead of my time, but I don’t think it’s that simple. I really don’t know. It’s like riding a big wave, right now. I’m just trying to keep sane. It has turned out that people who were gods to me in the ‘80s have not made sustainable contributions. I would never have thought that when I was a kid. I’m thinking about Jay Defeo; no one gave her the time of day when she was alive. Nobody paid any attention to [Philip] Guston, and his work is so seminal and is influencing so many people.

You were not only in the Whitney Biennial, but also on the catalogue cover. How did it feel to receive so much recognition after having been at it for a while?

I’m wondering if all artists have a tough time during their career and if it’s better to have a tough time in the middle or in the beginning. Mary Heilmann is my role model; we are very good friends. I don’t think she had anybody paying any attention to her until she was in her later 40s.

What have you done recently?

The last person I photographed was Stephanie Seymour. I’m doing a commission for her husband who commissions artists to do portraits of his wife. She has four children. So, I did a series of photos of her kids sucking the life out of her. She’s the epitome of glamour, she’s got the body of an 18-year-old, and she’s got four kids and nobody has ever worked on that aspect of her spirit. It’s a 21st-century Madonna and child. There’s an image in January’s W magazine of [Stephanie and her child] and when I gave it to them they asked if I had anything less provocative.

So, you know that people think your work is provocative. Why do you think they feel this way?

You’ve got me. I’ll never figure it out. I’m just not of this world.

Well, what other kinds of art or media appeal to you?

I am attracted to the transgressive; artists like Paul McCarthy and Cindy Sherman. I like movies that are complicated and make you want to talk about them after you leave. I loved 21 Grams—very complicated. The Wire is brilliant. And there’s nothing tidy in that show. That’s probably the best thing I’ve seen all year. It’s very real. We’re always looking for black and white in this world and it just doesn’t exist. I love it when people can make a picture of the grays.