Ryan Schneider’s work is preoccupied with narrative. Color, texture, and natural imagery become language and through it he records small moments of connection and alienation. Globs of paint depict pensive and ambiguous moments; the work says that self-restraint is only worthwhile if it breeds clarity. The show is on view through Feb. 20, 2010, at Priska Juschka Fine Art in New York City.

Ryan Schneider was born in 1980 in Indianapolis. He lives and works in Brooklyn. He holds a BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, and has shown in numerous solo and group exhibitions in New York, Los Angeles, Copenhagen, Dresden, London, Seoul, and Toronto.

I’m not in New York right now, so I haven’t seen the images in person—neither have a lot of our readers, I’m guessing, so can you give us a sense of texture and appearance?

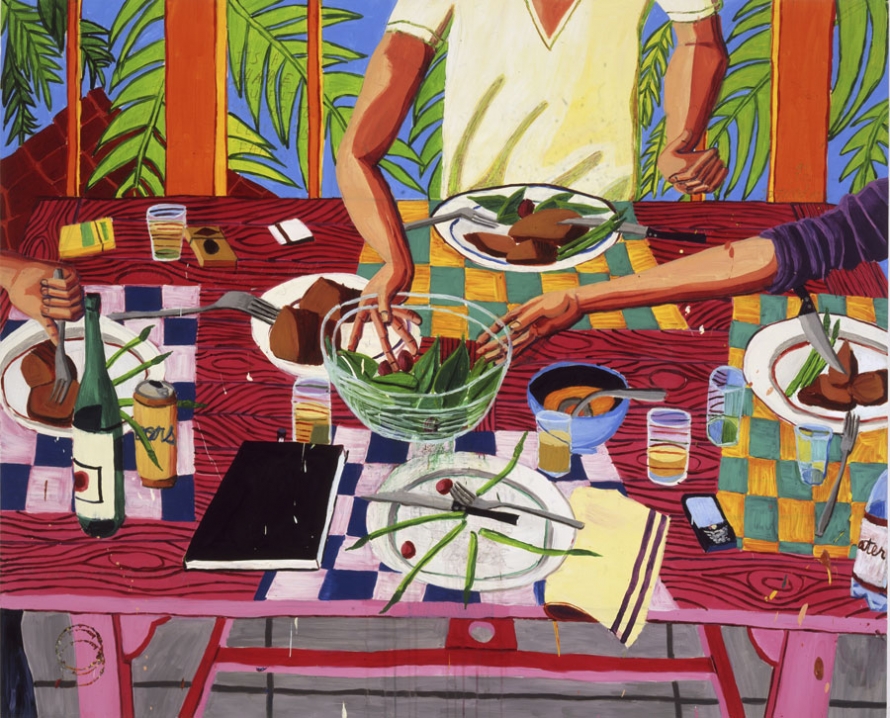

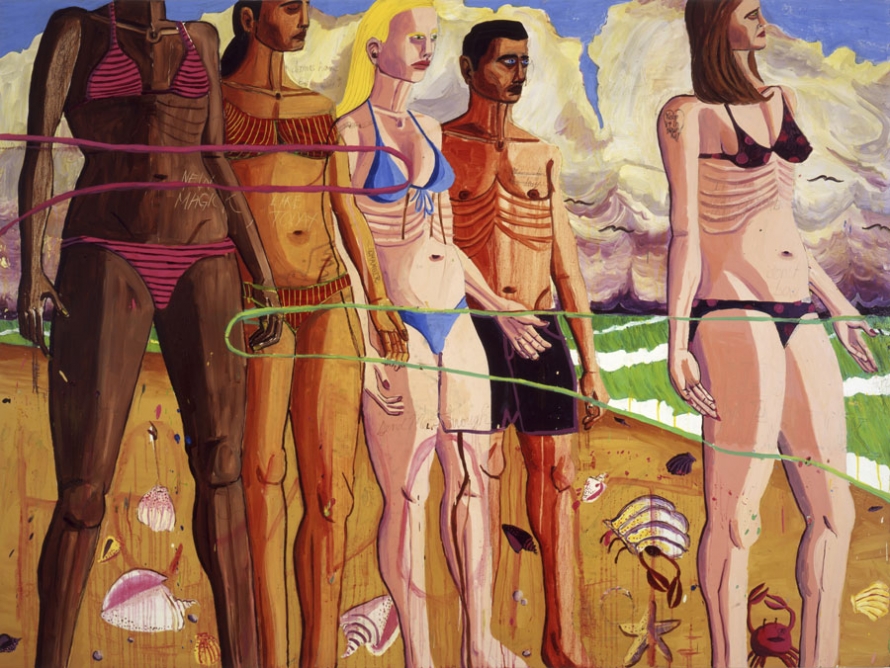

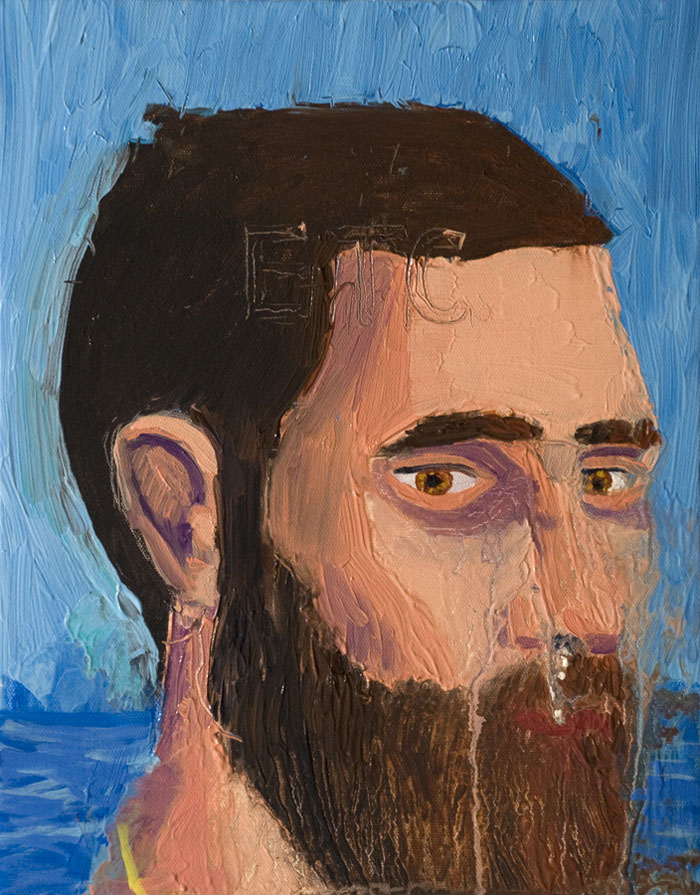

My paintings are extremely physical. The act of painting is for me a huge part of the process. The paintings are really large—the biggest one, with the shark, is eight by 14 feet. I use really thick paint in some areas and really thin in some areas. I use oil paint, so it stays wet for a long time. While I’m working, there will be layers of wet paint and I’ll also be carving into it with a pencil, writing words that come to mind and accentuating form with the carved-in lines. On top of all that, I might start cleaning my pallet off and just take all the paint that’s on the razor and just fling it at the painting, so there are these globs. The end result is multi-layered; it’s very textural. People want to touch them. When I don’t like something I scrape it off with a pallet knife and paint it back on, which will always create interesting texture and interesting layers.

Where do the images—contemplative couples, friends, dinner tables—come from?

I read the newspaper all the time. I get my inspiration from the images I work off of from everywhere. I’ll take a photograph while I’m watching a movie, or whenever I travel—I live in New York, but I like to be in nature as much as possible. I go to California a lot and I take pictures of mountains. Sometimes a photograph, it could be of anything, it pops out at me and I see its potential as a painting—the composition, or the action, what position the figures are in. I do a small drawing to plan it out and then I move to the canvas. I’ll have that hanging in my studio for a while, looking at it, and one day I’ll feel like, OK it’s time to make this painting.

Getting from that original reference to the painting—it’s something entirely different by the time the painting is done.

How did you end up painting disabled activist Harriet McBryde Johnson?

I saw this picture of her in the New York Times Magazine. Her story was beautiful, and I was blown away. I was so struck by her beauty. I knew I wanted to paint the picture; I knew the state of her body didn’t match the state of her spirit and her mind. Staring at the camera, like, yeah this is who I am. It’s weird, I know a lot of people know who that person is and maybe it was a bit lecherous of me to paint her portrait, but at the same time it was such an arresting image I could just see a beautiful painting there.

So where does narrative come in to your work?

In the last show I had here, most of the images were of me and my girlfriend, Dana. I’d find a picture of two figures in a room doing something and when I transcribed it, it would be me and her. There was always a kind of unspoken tension and action between the two figures. That was something that kind of happened naturally. When I was working on them, I was looking for an Adam and Eve kind of everyman, everywoman, hoping the viewers could project their own narratives onto it, which was very naïve of me because if you’re looking at a self-portrait of an artist you can’t really get past that. It was somewhat about our relationship and somewhat about human relationships. With the new work there’s a narrative that’s more specific in the figures I choose but they’re not me or her or anybody I know.

What’s the role of scenery in your work?

I grew up outside of Indianapolis, and I just really respond to landscape and natural scenery, I guess. There’s something about living in the city and painting the country. It’s a little bit of an escape for me. My girlfriend and I were in Cape Cod a few weeks ago, I’d never been there, and there was a crazy snow storm, and we were driving around and looking at all these houses, and she said, “don’t you think it’s weird that this is the first time you’ve ever been here, but that you painted all this stuff for your show.”

It’s almost like theater, or setting up the right shot for a film, the right setting for whatever narrative is happening in the picture. I’m not trying to make them look real. I’ve never taken a canvas out to the forest.

Is the audience supposed to transport itself into the painting?

My paintings are human scale; you stand in front of one, chances are the figure in it is sort of in proportion to your body. I do that on purpose to make the viewer be able to relate to them and their scale. It’s a bit more of a cinematic experience. It’s something you can kind of get lost in.

You mentioned that you sometimes carve words into your work and I know you’ve published a book of poetry—how is language and poetry connected to your painting?

I’m maybe like a recovering poet. I haven’t written poetry seriously in a few years. But definitely from 2000 to 2003 I was writing a lot and self-publishing zines. I have my own relationship to language and words. I don’t pretend to be a poet in any real sense of the word. I know real poets who are really investigating language, but for me poetry was just about vomiting out my experiences and feelings. When I was in art school it wasn’t cool to make art that was just expressing yourself. When I started painting the kind of paintings I make now, they started to fulfill that need in my own life and the need to write was sort of sated.

When I’m painting it’s almost like writing a story or narrative of a type, and these words just sort of popped in my head—or it’s a song I’m listening to, there are some song lyrics in there. Things that seem pertinent to that moment when I’m making the painting. If it looks bad I’ll paint it out. It’s a very subconscious thing. I’ll paint an image and that image will trigger a memory of when I was 13 smoking my first cigarette in the middle of a field somewhere at night, and I’ll just write, “field at night.” It’s a lot of stuff to do with memory; I’m a very sentimental person.