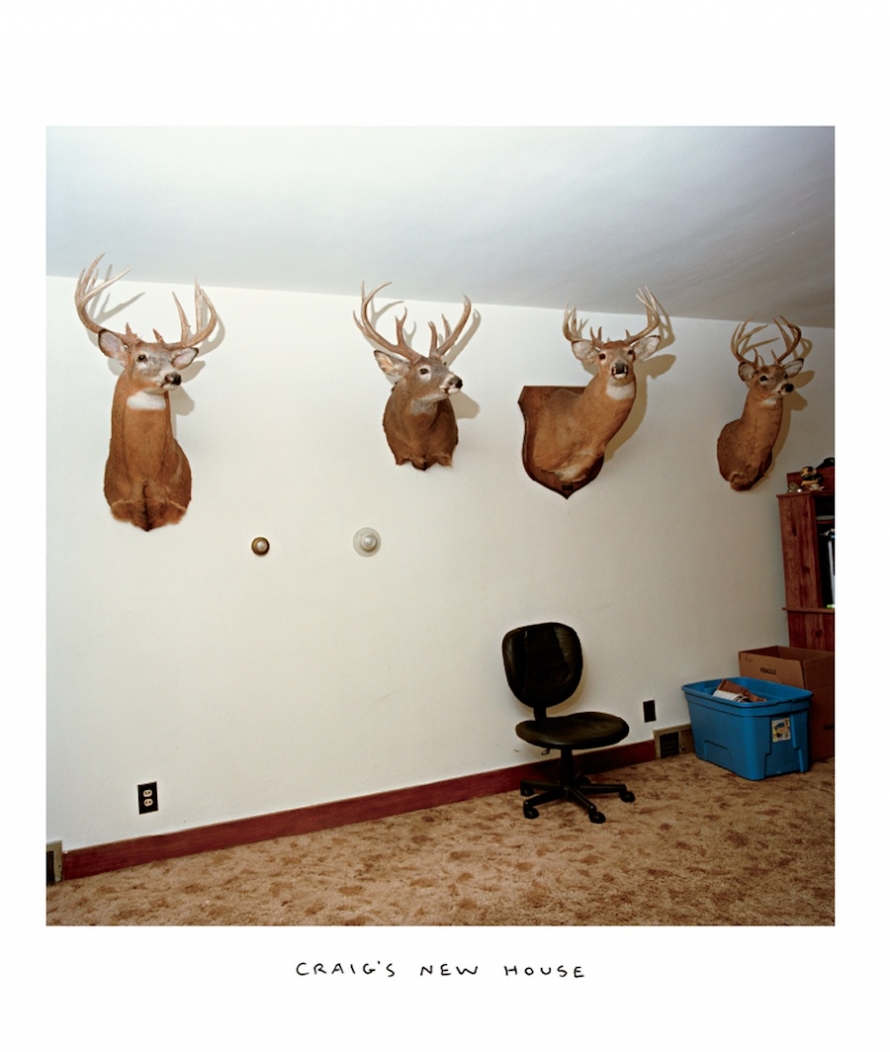

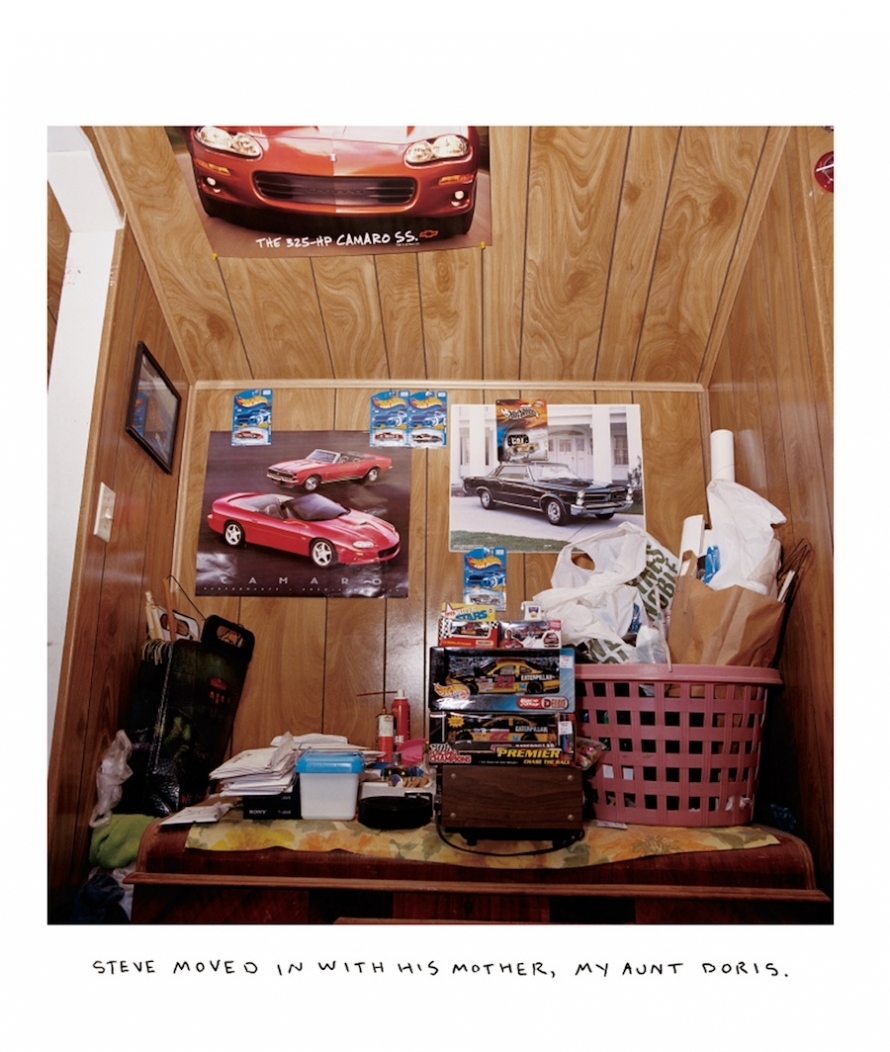

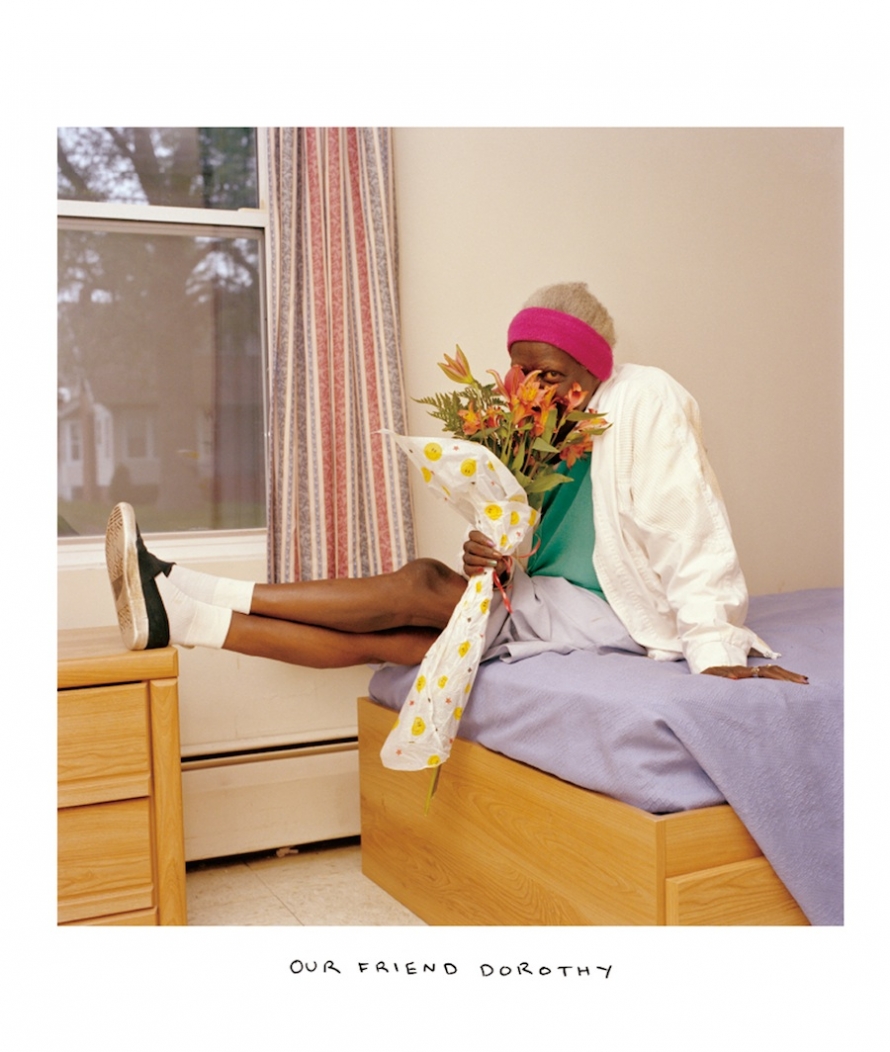

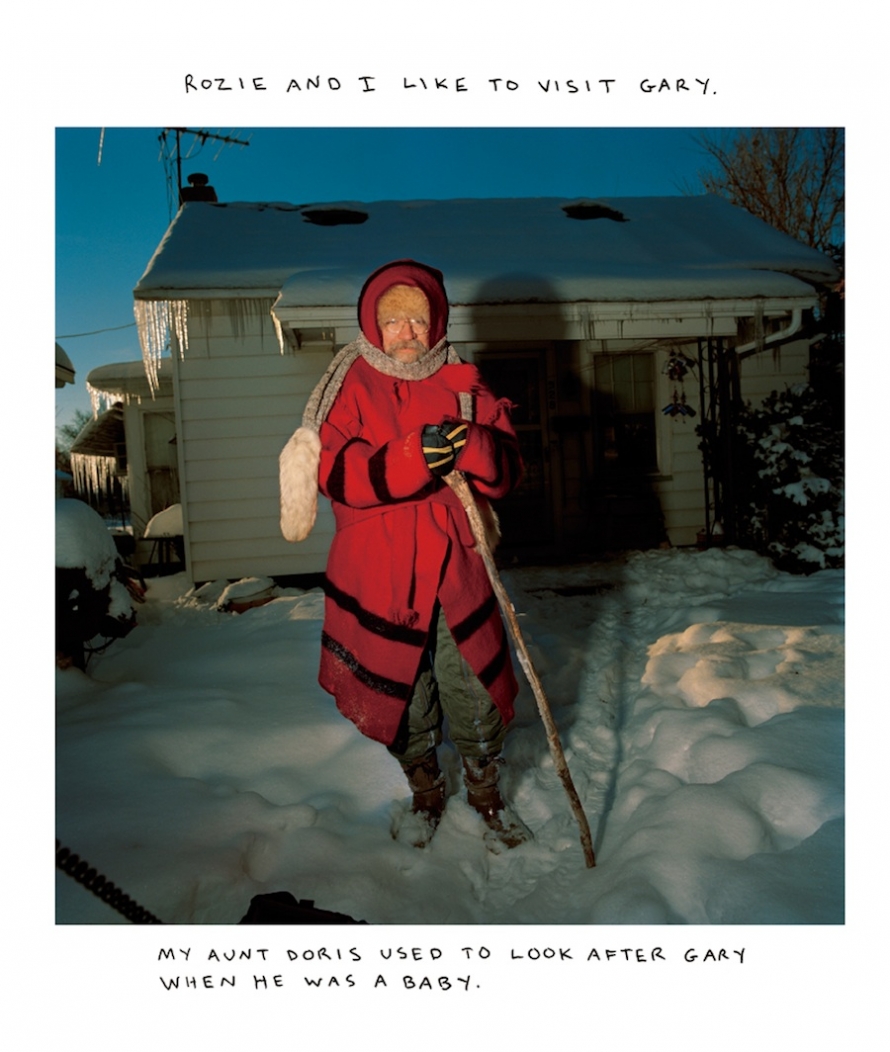

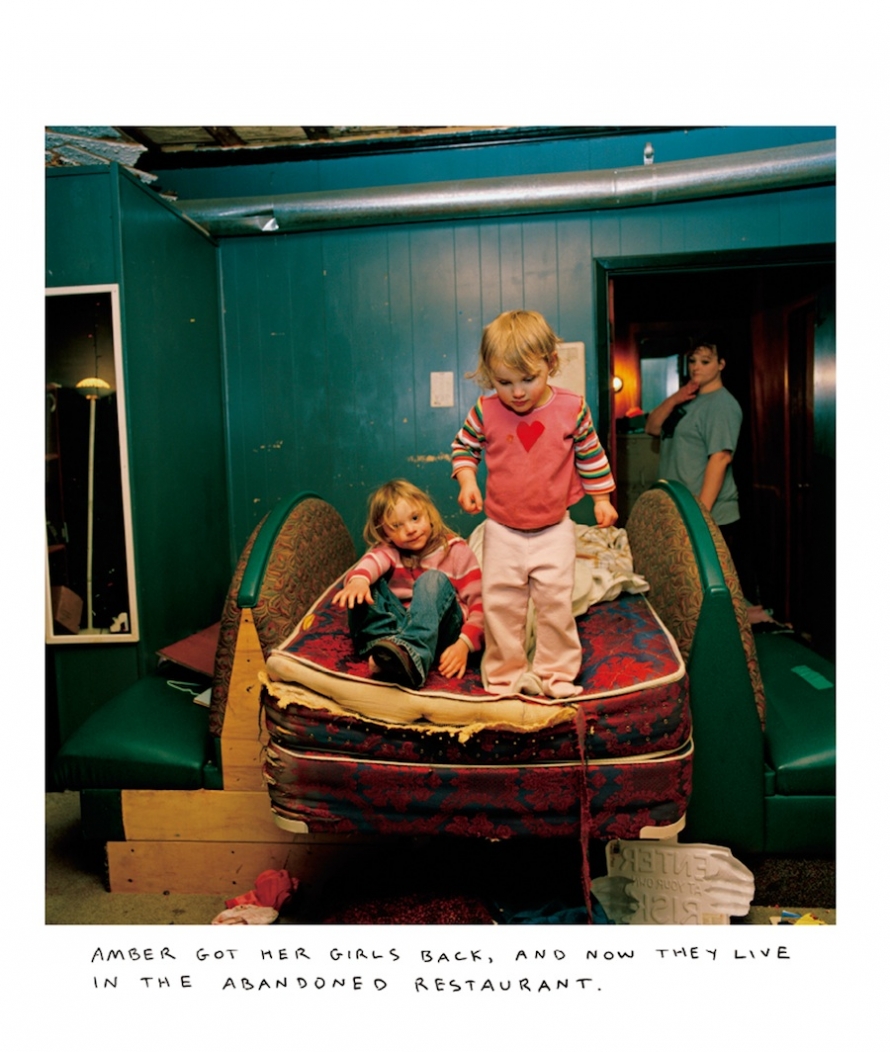

We’ll just come out and say it: A lot of photography and art books pass across our desk each year, and Chris Verene’s Family (Twin Palms) is the finest we’ve seen in 2010. It is marvelously engrossing. Family follows Verene’s family and friends in Galesburg, Ill., over 25 years, and the journey for the audience is—emotionally, intellectually, aesthetically—flat-out riveting.

Chris Verene was born in 1969 in Galesburg, Ill. His work has been widely exhibited and is held in many public collections, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. “Family” has recently been on view at New York’s Postmasters Gallery; a closing reception will be held this Friday, Oct. 15, 2010. Last week, “Family” opened at Marcia Wood Gallery in Atlanta. Further information can be found at chrisverene.com. All images © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

When you pick up the book, what does it mean to you that the subjects are family and friends?

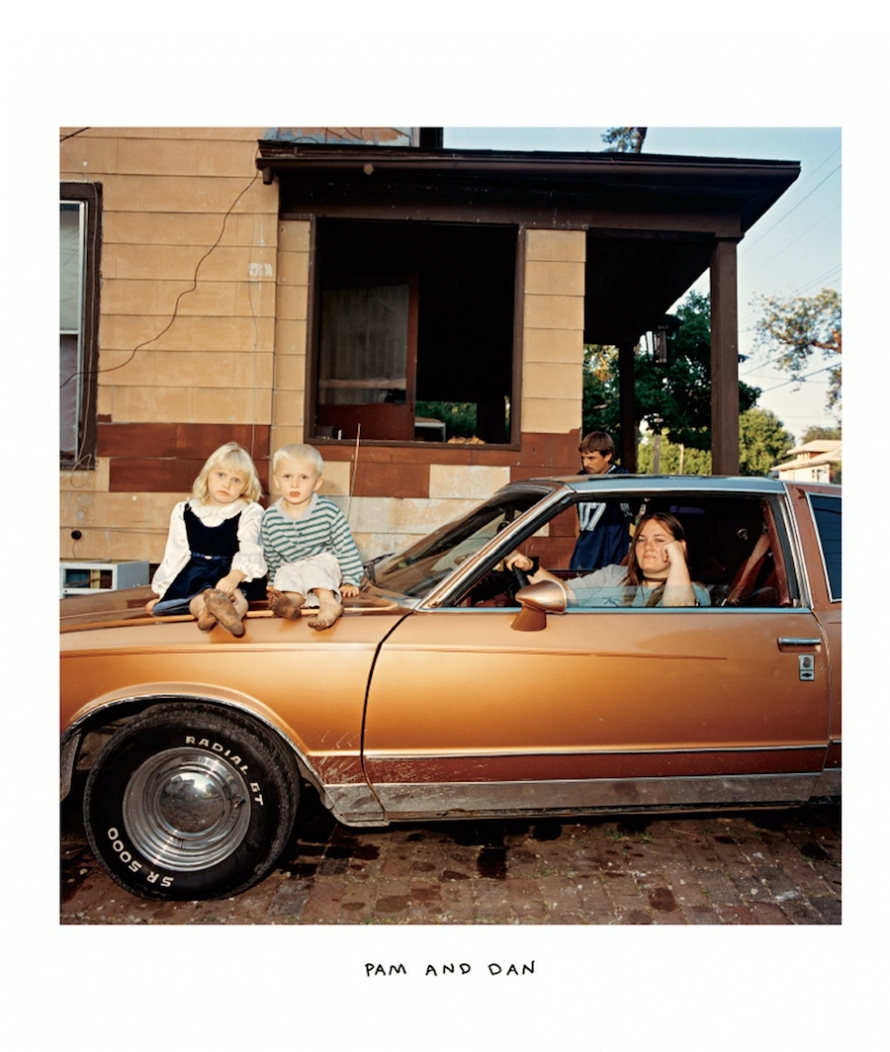

The books—I also mean to include the original book from 2000, Chris Verene—both books are made as a letter to my family and close friends. Although, by the time you, the audience, get to see the pictures, the people in them are already familiar with them over a period of years. Often my pictures are on walls in Galesburg a long time before a gallery or museum makes a debut of them.

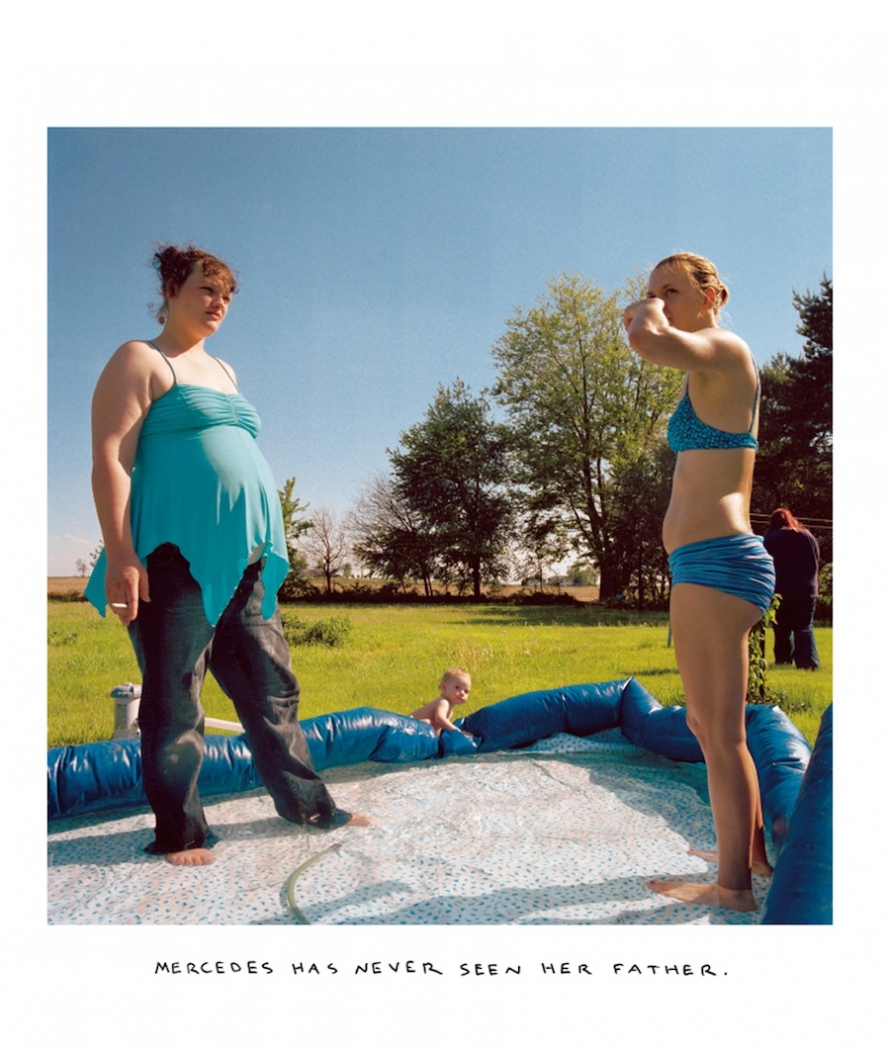

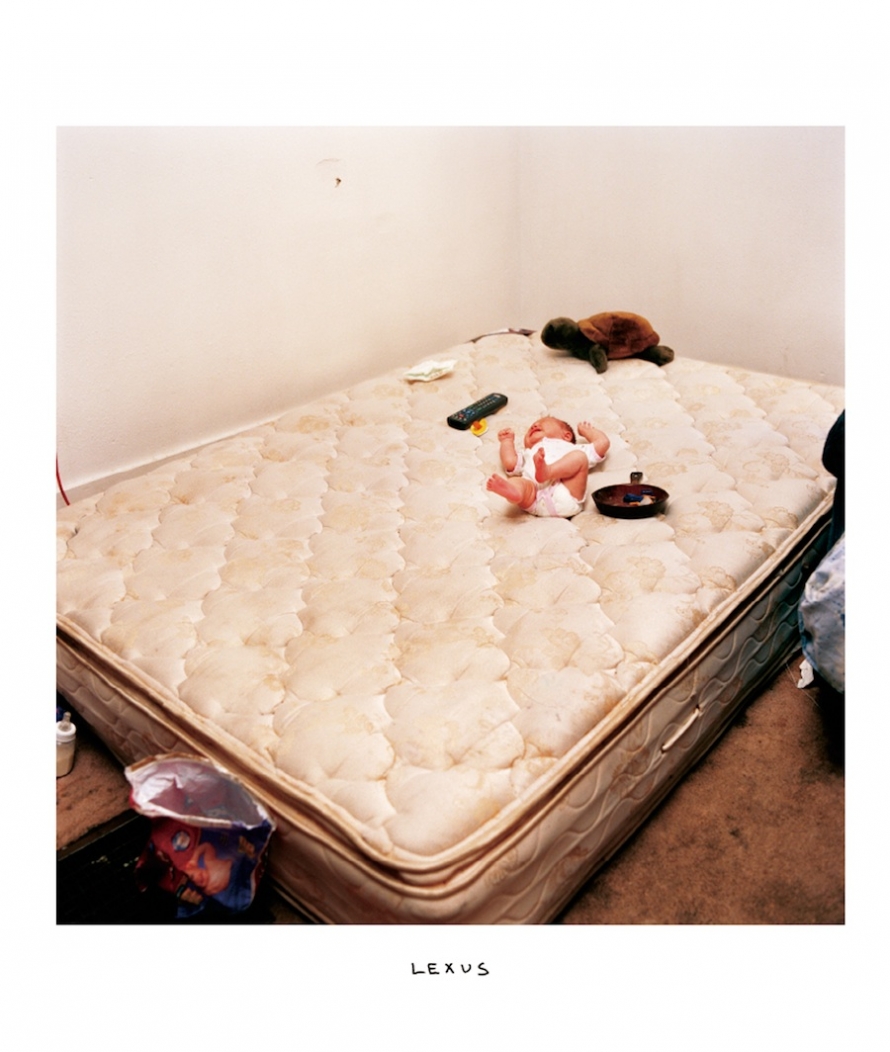

The book as a whole is like writing a letter to everyone in it. It’s a way for me to sum up a lot of the topics that have been important to the people in the story under one roof. Oftentimes the book is finally a message about the people’s most serious moments that they have shared with me.

When you were putting the book together, were you able to observe the images objectively? How do you compose the captions for the photographs?

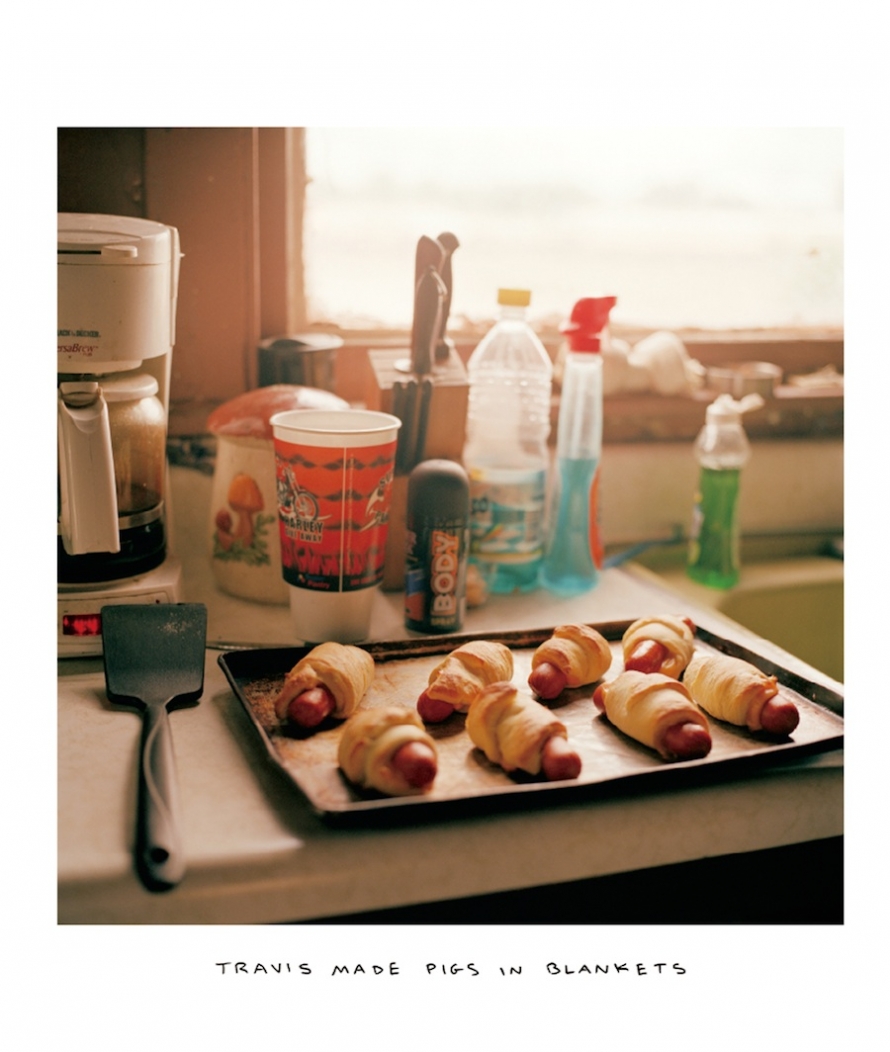

The images and sequence begin to form naturally over years. I make tens of thousands of pictures, and edit them into boxes. The boxes then float around, with certain pictures coming out and into a final box, often with handwritten caption drafts taped to them, so that I can try out the language on people who live in Galesburg, my parents and other family members, for accuracy and similarity of language idiom and usage. For example, “Shut-in” is not a universal concept, but it is very common in Galesburg, appearing as a title in Church bulletins.

For this book, I worked with Colleen Casey and Jack Woody on deciding how to cut things in or out of the book.

How to remain objective is tricky, and sometimes I cannot see what the clearest pictures are until I have tried them out on people over several years time. Other times I will see a flash of light and I’m sure of something.

There appears to be an enormous amount of trust between you and your family and friends. Have your gallery/museum shows and publication brought you closer or put distance between you?

I was very concerned in ‘98-99 when the first book was coming out that it might wreck the balance that made the work—that bringing fame to the project would spoil it’s chances to continue. I was relieved. I think the biggest shake-up from the fame of the work was when the local Galesburg newspaper did an above- and below-the-fold giant story and book review. My cousins at the Maytag factory said it got posted on the bulletin board at work. I do exhibit the pictures most summers in Galesburg during Railroad Days (the one and only small public carnival each year), with an aim at bringing generations and differing groups of people together in one place to see pictures of each other in downtown Galesburg.

I think trust is paramount to the work, and I think after photographing for 26 years in the same living rooms and kitchens, there is nothing blocking the way to truth and mutual respect.

I got to wondering about your “Self-Esteem” project in comparison to this book. The pictures in Family are beautiful, but they’re not there to make the subjects feel better about themselves—even if they do, they’re also much more than that. As the artist behind both series, how do you see your subjects?

As an only child, I think I kept my family close, and spent so much time in Galesburg, that even when we lived elsewhere, it was home to me. My cousins were like siblings, one in particular who nearly shares my birthday, and that is all still most dear to me. I was not close to my mother’s side, so Galesburg and the people were giant figures as I grew up. Travis’s family feel like cousins, and we are perhaps remotely related by a marriage. I think the deeper the relationship, the more I know I must always be close to the people—I mean that they count on me showing up and sharing important things in life. I will always be there.

What are you working on now?

“The Self-Esteem Salon” is a very different project, so far not staged near Galesburg. We are making the 12 years of documentary film footage into a feature movie. As performance art, I feel the only way to understand that project has been to actually participate. The movie hopes to approximate that experience.

Further, I am into the third year of work and planning with running the photography department at State University of New York, Westchester Community College. This means I am teaching students from the Bronx, from low-income areas, and others who have serious difficulty with learning systems. They are wonderfully motivated to make artwork, and it’s very rewarding work. I get invited to teach and guest-teach all over the world, and this is my favorite student body: the urban community college.