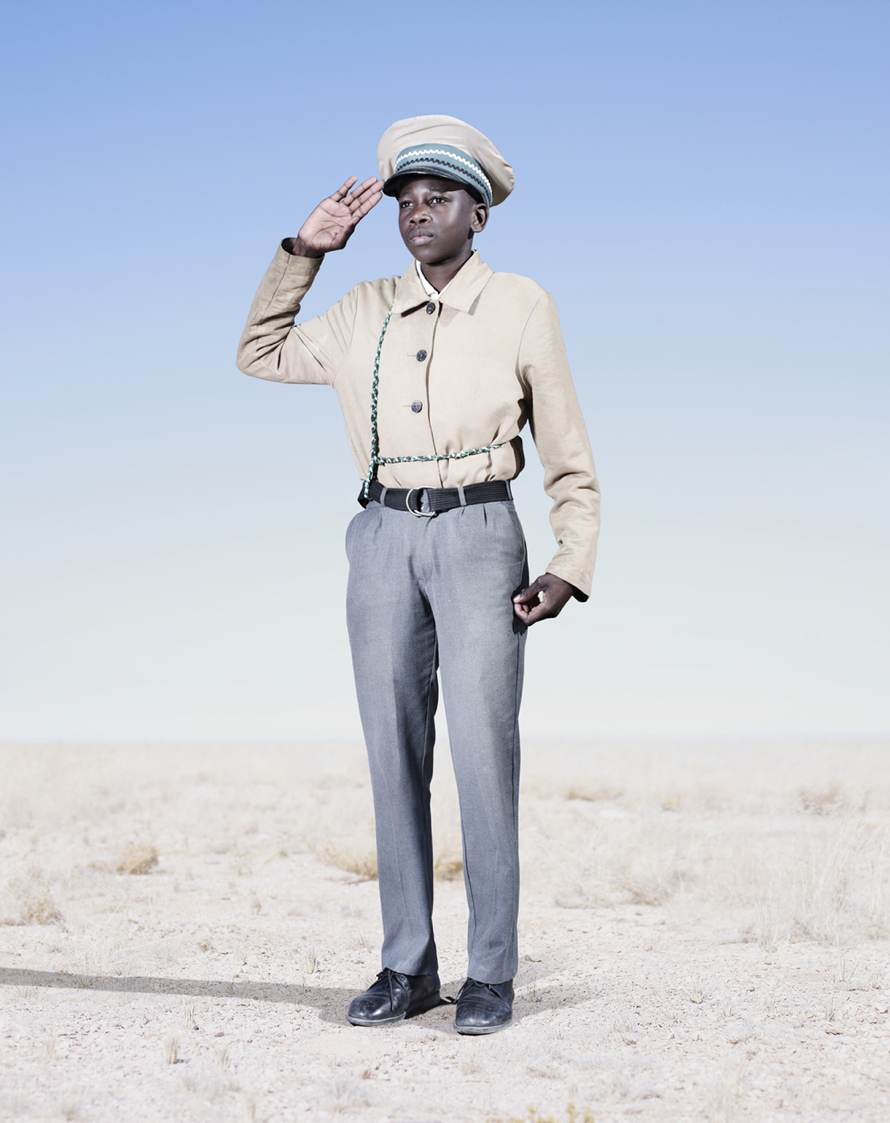

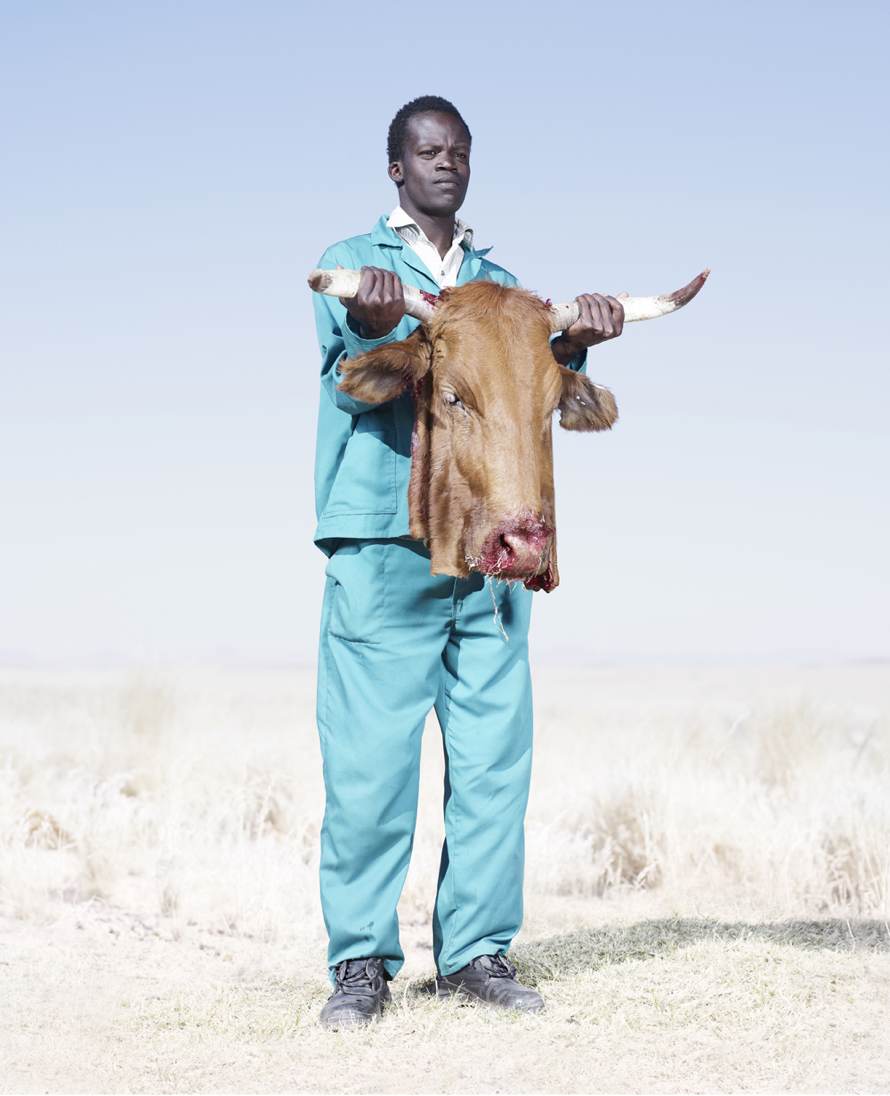

Costumes and Conflict

The Hereros of Namibia added Victorian fashion into their traditional costume under German influence in the late 19th and early 20th century. Photographer Jim Naughten explains how he became fascinated with this community.

Interview by Karolle Rabarison

The Morning News: You first encountered Namibia as a recent college graduate. What were you doing there? Did you interact with the Herero people then?

Jim Naughten: A friend and I decided to buy motorbikes and ride across Southern Africa after college. I took my old film camera not quite knowing what I would find to photograph and more or less stumbled into Namibia and across the Hereros during that trip. I was spellbound. I was not expecting to see deserts, ghost towns, Bavarian architecture, First World War relics, or tribes wearing Victorian-era dresses. I felt as if I was on a Wild West movie set where they had ordered all the wrong people and props. I photographed both the Herero and Himba people on that trip, but always had it in the back of my mind to return and make a more accomplished body of work on the Herero. Continue reading ↓

Jim Naughten’s “Conflict and Costume” is on view at New York City’s Klompching Gallery through May 4, 2013. The series also appears in Naughten’s book Conflict and Costume: The Herero Tribe of Namibia, recently published by Merrell. All images used with permission, © the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

TMN: How did you scout models for these portraits?

JN: I hired a Herero guide, and we traveled all over Namibia together, visiting and staying in Herero villages, and as guests at weddings, funerals, ceremonies, and gatherings. Whenever I spotted someone who looked photogenic—more or less everyone!—we would stop and ask if I could take some pictures, paying cash or giving coffee, maize, and sugar to chiefs and elders.

TMN: What was most challenging about setting up the shoots?

JN: The whole process was quite physical: camping every day, cleaning and charging equipment, driving thousands of miles off road. And that’s before taking any pictures. We had a few close shaves with snakes and scorpions and had to avoid the occasional elephant. Over a period of four months it can be a little draining, but overall it was a wonderful and highly rewarding experience to spend so much time immersed in someone else’s culture.

TMN: From what I gather, painting was your first foray into the arts. Why did you shift your focus to photography?

JN: I ended up switching and specializing in photography at art school, partly because the cool kids were doing it (I wasn’t one!). I think I was too impatient to paint, and photography seemed to get you out of the house, which appealed to me. I sometimes think of myself as a lazy painter, but in reality what I end up doing is lugging tons of camera equipment around and probably working much harder in the long run. Post-production, or Photoshop—oh, for a more romantic description!—is now absolutely central to my practice, so in reality the way I work now is much closer to painting and feels somewhere in between the two mediums. I plan to return to painting at some point, but I have no idea when that point may come.

TMN: What have you learned about yourself in creating the “Conflict and Costume” series?

JN: It has cemented the idea that I “make” pictures, rather than simply take them, and confirmed a working practice in that sense. Otherwise it was a kind of backwards step but one that I really wanted or needed to make before my next project, which will be something very different indeed. I hope to learn something about myself then!

TMN: You’ve spent a chunk of time researching and reading about Namibia and the Hereros. Could you recommend a book for our curious and history-loving readers?

JN: I can recommend a couple of books. Firstly, The Kaiser’s Holocaust by David Olusoga and Casper Erichsen, which is a harrowing account of the German-Herero war and makes a connection between the genocide and the roots of Nazism. Another book that I would recommend is Innocents in Africa: An American Family’s Story by Drury Pifer, which, despite not having a direct connection to the Hereros, tells the story of an American geologist’s son living in Southern Namibia and South Africa and trying to navigate his way through German and Afrikaner society. Lastly, if you can find a copy, there’s a very strange book called On Wings of Fire by Lawrence Green, written during the 1940s and 50s. It’s a collection of bizarre and gruesome “Wild West” stories about Namibia (then South West Africa) that will probably disappear altogether with the book. From the German woman who trained baboons to ride sheep to the diamond-rush days’ desperate guano hunters on Shark Island who would kill each other and remain preserved for years with bright orange hair (from the ammonia)—the stories sound a bit like early Nick Cave songs.

TMN: And could you tell us about this next project?

JN: I can’t really talk about it until it starts to take shape. All I can tell you is I’m going back a bit further in time/history—it should be an interesting trip.