The Orchestra Checks Its Email

A day in the life of a professional orchestra—coffee, practice, social media, tuxedo—leading up to a performance.

In The Philharmonic Gets Dressed, a 1982 children’s book written by Karla Kuskin with illustrations by Marc Simont, the members of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra prepare for a performance. They bathe, put on underwear, do their hair, and get dressed for work. Their daily lives stand out—enough to entertain legions of kids (and their parents).

More than 30 years later, we talked to a handful of professional musicians to see what’s changed.

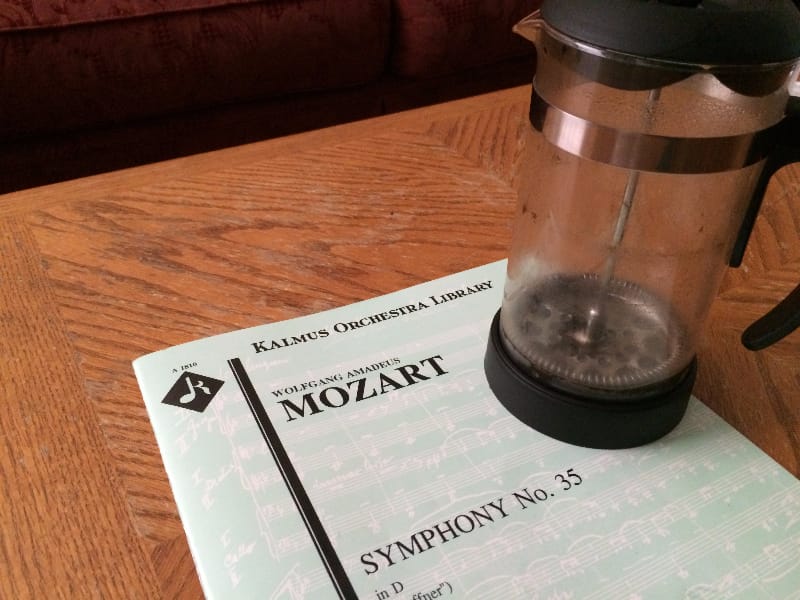

Morning

At 8:00 a.m., the San Francisco violinist wakes up—unless he got back late last night from a performance. He needs coffee, stat—he’s cut down to one cup in the morning—and makes himself breakfast.

The bassist wakes up between 6:00 and 6:30 a.m., thanks to his kids. He showers and grabs a bagel or cereal at home, plus coffee or espresso, two cups a day.

For the violinist, sometimes it’s cereal or toast, but sometimes it’s bacon and an egg scramble. Every once in a while he’ll walk a few doors down to a café to be around other people.

The pianist’s iPhone alarm wakes him up between 7:30 and 8. He checks his email and eats a donut or muffin for breakfast, and drinks coffee “fiendishly.”

The Monterey violinist gets up early every day—she has a day job working at an elementary school.

The director wakes up between seven and nine, depending on whether his day will be more administrative or artistic. “A music directorship requires a balance between the two.” He reads email on his phone while he makes coffee (two cups in the morning, but the second one usually turns cold and is left unfinished). He showers and has a piece of toast or fruit in front of the computer.

Mid-Morning

The San Francisco violinist emails and does some work online until 10:00, which is the earliest he can start practicing without waking his housemates. He usually clocks four hours a day at home, warming up in the morning with a cup of coffee in hand.

The pianist runs errands (if he needs shampoo, socks, or beer), and walks to work at NYU, where he teaches undergraduate private and group piano lessons. He uses the NYU practice rooms to practice anywhere from one to five hours each day. As he’s an accompanist, there’s also a singer about thirty percent of the time.

The bassist drives to work (listening to talk radio) at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where he teaches undergrad and graduate students. When he can find the time to practice, around teaching, rehearsing, performing, and family time, it’s usually a couple of hours at a time here or there.

On the weekends, the Monterey violinist might head next door to practice duets with her neighbor, who plays piano. Otherwise, she practices at home, sometimes pulling up a new piece on YouTube to listen and watch, either with or without the music in front of her.

If the director is studying orchestral music or doing administrative work from home, he can stay in pajamas until almost noon. He practices the upright bass, an instrument he’s kept up with; he remains a performer. Sometimes his neighbors in the apartment building can hear him practicing. They don’t seem to mind.

Lunch

The San Francisco violinist tries to make lunch quick—either leftovers from the fridge, or a trip next door to the market for a sandwich. The bassist usually has a salad. The pianist grabs a sandwich, “or a candy bar.”

Afternoon

The San Francisco violinist goes for a run, then showers. He teaches once a week, a middle-aged woman with two sons, and he suspects that it’s less about pursuing mastery of the violin and more about having time that’s just hers. On the way home from the usual errands, the violinist bumps into his landlord, “a wonderful old Dutch carpenter who’ll talk your ear off.”

The director teaches a few private students in his home, but mostly his job entails managing the faculty of San Francisco Symphony members who mentor and teach the post-graduates in the Academy fellowship program. His email paperwork is endless. He even has a recurring nightmare about it.

As one of said faculty members, the nearby violinist also does some paperwork for the San Francisco Academy Orchestra, emailing the fellows and coordinating classes and mock auditions.

The violist emails and texts clients and fellow musicians to coordinate rehearsal schedules, hire other players, and communicate with clients.

The Monterey violinist gets home from work between 4:00 and 5:00, emails potential wedding clients and responds to performance opportunities—and drinks another cup of coffee around 4:00 p.m. if there’s a late performance ahead.

Preparation

The bassist changes the strings on his instrument every six to eight months, and does repair work as needed. Other adjustments, such as those for the sound-post, can be annual.

The San Francisco violinist takes his instrument out every day, tightens the bow, applies rosin if needed, tunes the fiddle, and he’s done. Long-term maintenance involves more complicated visits to luthiers. He owns a French instrument made in 1921. “I’m but a caretaker of this piece of history. After I’m done playing, this instrument will go on to someone else just as it has many times over since it was made.”

The director teaches a few private students in his home. His email paperwork is endless. He even has a recurring nightmare about it.

The Monterey violinist changes her strings about four times a year, and has the bow re-haired at a shop once or twice a year. After every session, she cleans the rosin off with a handkerchief that lives in the case. She tunes her violin with an iPhone app called Cleartune.

The viola seems grueling: it requires tuning frequently, several times per hour of playing. The violist rosins the bow every day or two, as well, and changes the strings every three to six months. He, too, sees a professional luthier to re-hair the bow two to three times per year.

In the weeks leading up to a concert, many of the musicians rehearse every night or every few nights, culminating in concerts Saturday and Sunday (and sometimes Monday). The Monterey violinist usually schedules rehearsals on the weekend, too, since her day job fills most of her weekday hours.

Dinner

On a concert day, the director goes out to dinner with colleagues. If it’s an administrative day, he’ll usually go to dinner with a donor or colleague, something work-related.

The bassist’s wife plans dinner on concert evenings—nothing too heavy, and he never drinks before a performance. He plays with his kids for a while after dinner and then heads off to the venue.

The Monterey violinist plays with her kids, drops them off wherever they’ll be hanging out during the gig, does some last-minute practicing, changes clothes, and heads out. During big performance weeks, she grabs takeout or eats in the car on the way to the gig.

The pianist usually gets takeout, too. He never cooks.

Getting Dressed

“Performance dress is never ritualistic for me anymore,” the San Francisco violinist says. “Tuxedos and suits are so familiar to me that I don’t even think about the fact that, to most people, I’m getting really dressed up. It’s a uniform in the same way as a doctor putting on scrubs or a Yankee putting on pinstripes.”

None of the musicians lay out their performance clothes the night before, but the violist will spend a portion of his practice session in the tux, to get used to the feel and to adjust his shoulder rest. “Playing in different clothing changes instrument position, so adjustments are necessary.”

The tux-free violinist always finds herself in all black—usually either dress pants and a blouse, or a long skirt. She has a long black dress for special performances. Sometimes she has to check to make sure all the pieces are the same shade of black, since black clothing will fade differently and wreak havoc on her performance wardrobe.

Driving to the Venue

The San Francisco violinist travels all over Northern California for his orchestras, and listens to the radio en route, but often drives so far that they fall out of range of the station. Carpools are the norm for freelance musicians, who can travel long distances for smaller “freeway phil” companies. The Monterey violinist has a new car, a Prius, “since I’m sometimes driving 75 miles round-trip.”

“Tuxedos and suits are so familiar to me. It’s a uniform in the same way as a doctor putting on scrubs or a Yankee putting on pinstripes.”

When he’s not in the car, the violinist listens to the pieces he’s performing or using for upcoming auditions—a practice also employed by the viola player (who uses Spotify) and the pianist, who spends some time analyzing his music so he’s familiar with the score.

But when his brain needs to relax, he listens to power pop, instead.

The two or three musicians in the viola player’s carpool also listen to music. Today, it’s Milk Carton Kids. But when it’s not for practice or prep, he rarely listens to music on his own.

Performance

The bassist arrives at the hall early to warm up and review any tricky passages or solos.

The Monterey violinist is also early, 30 minutes or so, for some warming up and more practicing.

Before a performance, the pianist simply makes sure he’s relaxed. But he’s developed a little ritual recently: “I eat a banana and drink Vitamin Water XXX before a show. Just a good-luck measure.”

The San Francisco violinist makes sure he has a full stomach and drinks plenty of water, never alcohol. When he gets to the venue—inevitably early—he does some scales and, like the bassist, takes a look at any bothersome passages to form a mental plan of attack.

The violinist is stress-free. He’s been doing this for 12 years. “The work for this performance has been done and now it’s time to just go out and do.”

Post-Performance

The Monterey violinist likes to wind down a bit after a performance, sometimes with a glass of wine or tea and some TV or a book. She tries to get to sleep before midnight during the week.

For the San Francisco violinist, it depends on the commute back from the venue, which can run an hour or two. If he’s coming from somewhere like Fresno, or beyond, he might not find his bed until 1:00 a.m.

The director turns in between midnight and one, as does the violist.

Evan Buttemer is a freelance violist and member of several Bay Area symphony orchestras.

Shannon Delaney is a freelance violinist in Monterey and Santa Cruz with the Ensemble Monterey Chamber Orchestra, Santa Cruz New Music Works, Santa Cruz Chamber Players, and Western Stage.

Andrei Gorbatenko is the conductor and music director at the San Francisco Academy Orchestra.

Scott Pingel plays principal bass in the San Francisco Symphony and is on faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

Darren Sagawa is a freelance violinist in San Francisco who performs with the Santa Rosa Symphony, Fresno Philharmonic, Monterey Symphony, Oakland East Bay Symphony, Sacramento Philharmonic, and the San Jose Chamber Orchestra. He’s also the director of operations at the San Francisco Academy Orchestra.

Chris Piro is a pianist and professor at New York University.