A bright sans-serif sign announces the location as if for a lemonade stand—HAVE A SEAT / OCEAN PROMENADE’S NURSES WILL BE RIGHT WITH YOU—but this is a place where toes are denumbered, heels unrounded, and ankles disarticulated. Out of elevators, blanket-lapped four-wheelers are still emerging. Some trail tubes. They station themselves in peloton-like rows down the center’s hallway to the café, where multiple mop-wielding orderlies hoof back and forth at the front of the lunch line, demarcated by a cautioning yellow placard. It is 10 past 10. The semi-private room of 54-year-old Von Brunson is at the far end of the second floor, above the patio where a young girl brushes sand off the tennis-balled bottoms of her grandmother’s rhinestoned walker. The Beacon—known as Ocean Promenade until Hurricane Sandy sent floodwaters up its rampways in 2012—is a newly renovated rehab facility in the beachy part of Brooklyn: Far Rockaway, the neighborhood where Brunson lives with his wife.

Back-to-back Steve Harvey reruns blare from a blinking 15-inch set; there is an immense amount of panning. Brunson leans on elbows over a chipboard table reminiscent of the design of a middle-schooler’s desk—only, the brown metal legs, instead of going straight down, bracket out, allowing a wheelchair to pull up to the edge. Brunson’s right foot sits in a protective boot (“lest I stub toes,” he jokes), while the left (the left is why I am here) is, in fact, in absentia, having been divorced from the New Yorker’s body one month ago. A sock squeezes the sutured skin at the stump’s end, which someone has covered further with what looks like a baby’s knit cap.

“My daughter made two—one for my grandson, one for me,” says Brunson. “It’s itchy yarn, but that’s good because sometimes I forget what happened… I heard of a woman who’d fall out of bed every morning not remembering her foot wasn’t there… just this sickly moment of surprise, y’know like when you’re climbing stairs in the dark and you think there’s one more step than there is… the itching helps me readjust the way I think of things.”

Brunson is, tragically, a poster child for diabetes: black, overweight, legally blind, renally inert, dialysis-dependent, and now one-legged. He alternates periods of imperceptible breathing with deep, shuddering catch-up breaths. If there is any incongruity, it is his cheerfulness, which he wields generously in the form of anecdotes and epigrams. Brunson, who turns 55 in November, enthusiastically tells me he has only had one birthday party in his whole life—in 2012, just less than a year before he injured his foot. By September 2013, after weeks of flashing fevers, he was admitted to St. John’s Hospital, where doctors found he had a diabetic ulcer midfoot. In no time at all, unstoppable bruising had permeated up to his lateral malleolus—the funny knob thing on the ankle—and searing pain, previously masked by neuropathy, soon became unyielding. An ER doctor cut a hole the size of a pencil eraser through three layers of skin on his heel, and ominous yellow fluid began pouring out. Brunson’s kidneys were tested: 6 percent renal functionality—infection had eviscerated them. Brunson was put on dialysis, and over the next few months half of his foot was scooped out through his heel. No attempts were made to revascularize, or surgically restore blood flow. Brunson’s wife, dissatisfied with her husband’s treatment at St. John’s, contacted ProHealth and was referred to Andrew Metzler, a vascular surgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. Metzler, within two minutes of examining Brunson, determined what those at St. John’s were unwilling or unable to: Brunson’s leg was not salvageable—things had progressed too far.

Fact No. 1: In the US, roughly one out of every 200 people has undergone primary (above or below-knee) amputation, according to the National Limb Loss Info Center: 45 percent due to trauma (unseen trains, for example), 54 percent due to peripheral arterial disease1, and 1 percent other.

Fact No 2: Of persons with peripheral arterial disease (PAD) who have a lower-extremity amputation, up to 55 percent require amputation of the second leg within two or three years.

Fact No. 3: In the US, black Americans are up to four times as likely as other racial groups to lose a leg—or three times, controlling for the disproportionate diabetes rates among them.

Fact No. 4: If diabetes and PAD continue to rise at the rate they have been for the last several decades, in just a few years, PAD—not trauma—will be the overwhelming reason for amputation. By then, our usual associations with amputees—with reckless boxcar hoppers, laurelled para-athletes, uniformed heroes (Lt. Dan, father and son Skywalker, etc.), and malformed children overcoming the odds—will need to be somatically adjusted, more or less, to the image of Brunson.

Amputation due to trauma is misfortune, but due to PAD is blameworthy negligence, because, as Metzler, Brunson’s surgeon, explains, “in theory 100 percent of [PAD-related amputations] are preventable, absolutely”—not only because their primary mainsprings, smoking and type II diabetes, are avoidable with the right lifestyle choices, but also because, once developed, PAD is fairly manageable with everyday dietary changes, diligent check-ups, and a half-decent pair of sneakers. And even if things do get bad, Metlzer continues, “I can stent the artery with something like an autogenous saphenous vein conduit [he loves to say it: autogenous saphenous], or put a balloon in… [which] are your minimally-invasive options: endovascular, they’re called. Or I can do bypass… which is where we try to revascularize by rerouting blood flow around blockages… Only if bypass risk is too high, [or the] arteries are too calcified or too small for stents, or say gangrene has totally set in, would I amputate.”

Metlzer performs about one below-knee2 amputation per month, of the 73,000 or so legs lost to PAD in the US each year. Because PAD primarily emerges due to poor primary care or misinformation among patients, and because it typically results in amputation only when providers fail to intervene at the right time with the right resources, Metzler, like many others in his field, considers this number to be the quintessential measure of how flawed health care is today—“the canary in the coal mine if you will,” agrees Philip Goodney, a vascular surgeon based out of Lebanon, NH.

Black Americans, for reasons not totally understood, are significantly more likely to have a leg amputated than whites, Asians, and Hispanics.

Marshall Chin, a general internist at the University of Chicago Medical Center, relates amputation to skewed financial incentives at play in the fee-for-service payment plan employed by most US health facilities, which are typically paid based on the volume, not the value, of services performed. “We make money out of complications. We are told that if we perform more surgery, run more tests, regardless of how it affects actual quality of health, we will be rewarded for it,” says Chin, who is optimistic about certain provisions in the Affordable Care Act that support the more value-oriented financial models. PAD, he argues, is largely an issue with insufficient primary-care coverage: “It gets to this idea that we ought to create strong links between primary-care doctors and their patients, so they can work together to prevent things like amputation from happening.”

But what PAD persistence reflects even more poignantly is something even more treacherous. A study, published last October, by Goodney and the Dartmouth Atlas Project confirmed nationwide what has been found among sample groups for the past decade: Black Americans, for reasons not totally understood, are significantly more likely to have a leg amputated than whites, Asians, and Hispanics.

Brunson covers his right eye with one hand and tells me all he sees is a wash of ceiling, floor, and walls, made entirely of light, but no sign of my face. But not to worry: If he swaps and covers his left, there I am, back again, “pretty blurry but looking young,” he says. In 2002, when flecks of black started showing up in his vision, Brunson was referred to a retina specialist, who‚ during the exam apparently gasped and stepped back:

“Did you drive yourself here?” he asked.

“Yeah,” said Brunson. “Why?”

“Because you shouldn’t be able to see the road.”

In the course of examination, the specialist found hemorrhaging behind Brunson’s eyes: retinal deterioration. It is hardly an unusual diagnosis for diabetics (up to 80 percent of people who have diabetes for more than 10 years experience some degree of retinal degeneration—in fact, diabetes is the leading cause of blindness in the US), nor was it surprising that Brunson had not noticed himself (until late stages, the patient’s vision goes unaffected). No, what surprised the specialist was—one—that based on the extent of damage, Brunson’s eyes had likely been bleeding since 1996, and—two—that Brunson had not been immediately referred to a retina specialist when he was first diagnosed with diabetes in 1991, as is standard procedure.

“[My primary diabetes doctor] had nothing to say when I told him,” says Brunson. “He knew he should’ve referred me.”

Asked about his decision to specialize in vascular surgery, Metzler reads me a quote from Cid Dos Santo, the Lisbon physician who helped establish the field: “Vascular surgery is peculiar because above all it is mainly a surgery of ruins.”

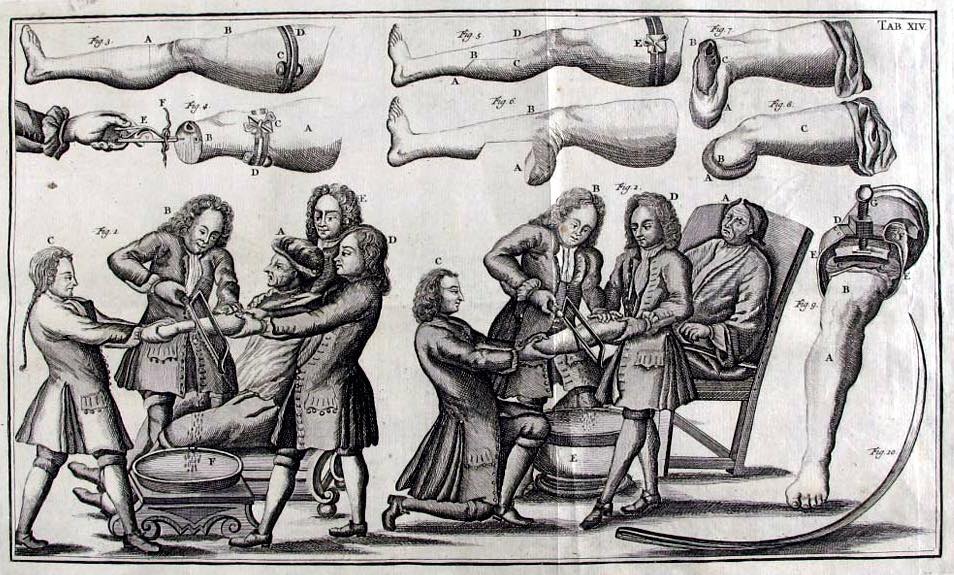

In a conference room library across from Metzler’s office is a copy of The Atlas of General Surgery by Schumpelick et al., Thieme Press, 2006. On pages 506-09, in dark photographs, it portrays the piece-by-piece removal of a dying leg. A long, circling knife slashes the putrefying meat, which has been swaddled in towels, yellowed in iodine, and manipulated through the rubberized whole of a paper drape so as to obscure the greater extremity. An asterisk notes that this aspect of the procedure has not changed since Neolithic times: a hand uncurls, its knife draws deeply, the way one slices a peach or a mango, the way husk leaves husk just as your cleaver finishes orbiting the nut. Next, a gigli saw is brandished, oscillating fast as it can up through the tibia, the fibula, flecking pure white until it hits marrow, until the toothed wire splatters up, and what is left is a gorgeous, exploded cross-section of nerve, bone, muscle, artery—but oddly there is little liquid to spill from the shrivelness. I think of the surgeon, whose face is not pictured, and the moment it takes him to find the limb’s point of balance before objectlessly uttering to an assistant to take it away. Soon, the bone is sanded, muscle and skin wrapped over its new end, and the surgeon, undone, catches his breath before dressing the fleshy nowhere.

“Difficulty: Easy,” says the caption.

It has long been known that diabetes disproportionately affects black Americans (13.2 percent of blacks are diabetic vs. 7.6 percent of whites), a fact that has largely been attributed to a lower average socio-economic standing (if you are poor, it is harder to eat healthy, to find time to exercise or go to the doctor, etc.). The violent 2014 asphyxiation of Staten Islander Eric Garner in the plainly clothed arms of the police, for instance, was catalyzed in large part by his poor health, according to the medical examiner. Garner was a hulking, 350-pound diabetic-slash-asthmatic with a heart condition.

But the Dartmouth Atlas Project found significant racial disparity in amputation rates even after controlling for disproportion in diabetes prevalence. According to 2007-11 data, black Medicare patients with PAD are 2.8 times as likely as other patients to have a leg amputated. In certain areas, particularly in the rural South, this disparity can be as great as 5.3 times (Monroe, La.). In New York, where Von once worked as a conductor on the F subway line, the disparity is 4.2 times.

Still, however, the very same socio-economic argument can be used to explain away the discrepancy, rendering it economic disparity, not racial. As Goodney explains: “In my clinical practice as well as when I looked at our data, I see that patients of low socio-economic status—patients on welfare—often do not know to take care of themselves, or maybe the clinics are far away, or they feel they cannot afford the care… not to mention they are statistically more stressed, which can contribute to worse cardiovascular health… or maybe because of family burdens, they lack time to take care of themselves; they will say, ‘I’ll get by with this pair of shoes even though they do not totally fit.’ We see it everyday: a pair of ill-fitting shoes can cause a sore or blister, and that’s the start of it.”

“You could have a white person and a black person go into the same hospital, see the same doctor about the same problem, and one walks out and the other is wheeled out.”

But then, even more jarring, is a 2013 study out of New Haven published in JAMA Surgery—one of two similar studies that almost every physician I interviewed independently cited3. In it, researchers controlled for things like progression, severity, co-morbidity, patient income, hospital rating, practitioner experience, and just about everything else that would correlate with socio-economic statuses in the treatment of PAD, and still blacks were 1.7 times as likely than non-blacks to undergo amputation.

“I don’t think I have seen such depressing data,” says Samantha Minc, a vascular surgeon who works at safety net clinics in Chicago’s South Side. “It basically shows that you could have a white person and a black person go into the same hospital, see the same doctor about the same problem, and one walks out and the other is wheeled out… I mean it’s possible—maybe the data misses something, a genetic difference maybe4—but that aside, there are only a few conceivable factors: one, black patients actually opt for amputation over revascularization, or, two—and this is the one no one wants to talk about—providers are making unfounded decisions based on race.” In the case of the former, Minc speculates that patient preference could arise out of a sense of fatalism, mistrust, or confusion.

Metzler concurs: “I mean, it should never be surprising that, if you’re just looking at the crude rates, African Americans have more amputations. I mean, African Americans have more diabetes, that’s a known issue itself… But what’s concerning is that even when you control for these things[,] even when you’re controlling for the institutional environment where they are being treated, there is less likelihood of undergoing these heroic revascuarization efforts before proceeding to amputation. That’s what is concerning.”

In March this year, JAMA published another study—one of many like it that have been published over the years—that found that while race did not ultimately impact clinical decisions, implicit racial biases were present in nearly all of the 215 clinicians surveyed. One startling finding was that clinicians were more likely to diagnose a young black woman with pelvic inflammatory disease rather than appendicitis when presented with the same set of symptoms for black and white patients. The data speaks strongly to a 2002 Institute of Medicine study’s finding that “for almost every disease studied, black Americans received less effective care than white Americans, [controlling] for socioeconomic and insurance status.”

Implicit Association Tests, which the JAMA researchers used, are available online for anyone to take, and have been around since 1998. For unsurprising reasons, they remain controversial in both their reliability and implication.

“You don’t want to believe that you could possibly be making snap decisions that might in the end be hurting people,” said Minc, who expressed embarrassment when describing how hard it actually was to remain totally impartial when she tried the test. “I think it would be good if more doctors took it—if anything, just so they are more aware of their unconscious proclivities,” she said, recommending medical education focus on shared decision-making between informed patients and providers as a possible course of remediation.

Of course, if there is bias, it is not necessarily malicious, explains Monica Peek, an assistant professor in general internal medicine at University of Chicago: “A doctor making a clinical decision may be thinking, well, this person is coming from a more disadvantaged background, so they may not be able to adhere to the medical regimen to help keep their vessels open, or may not have the social support, physical therapy, or wound care that they would need after a revascularization procedure, as opposed to an amputation, which is easier to care for after. We know that physicians make assumptions about people’s social support, their use of drugs and alcohol, and other things that they have not actually asked about. Such assumptions can color decisions, and race can be the proxy to them.”

Interestingly, speaking of his personal experience, Brunson described reverse-biases—white doctors acting almost paternalistically toward him: “I find I get treated better by people that are not of my race, but I’ve never known why,” he says.

Still, if the residual discrepancies in health care are explained, even just somewhat, by implicit racial biases, it is hard to have that discussion about amputations, an act which is itself so violent and painful for a surgeon to perform, especially when they have been working with the same patient over the course of many years. When I first spoke to Minc, even before she knew what I was calling about, she told me she was at Mount Sinai “trying to avoid performing amputations.” Later, when I reminded her of what she had said, she elaborated, “I amputate because I have failed—failed as a vascular surgeon, failed as a doctor… there are few words to describe seeing the patient after the procedure, disfigured… just shame.”

I asked Minc if she feels this way even when the patient came in so last minute, it was beyond her power to help.

“Is it possible,” she responded, “to spend decades removing parts of people, and emerge whole yourself?”

Our usual image of the non-ambulant is misplaced. We encounter monopedal panhandlers and are still immediately vulnerable to the suggestion that previous chapters of their lives unfolded unluckily in the Gulf or even Vietnam. But as one man reveals, sitting down and out on the corner of 95th and 2nd in Manhattan, propping his prosthetic as a stump-rest: “I ain’t no veteran—fact is, a few guys genuinely are, but most of ‘em you see out here, missing legs, only say it because it’s a better pitch than just saying diabetes took ‘em.” That’s Roy Griffin, 64, a type II diabetic, who did 24 years on crutches after a winning jump shot sent part of his fibula through his femoral artery. After bypass surgery he was told to keep off his feet, but when his kid brother went missing, he went out looking for him and botched the whole jig. A second bypass failed and amputation became necessary. Incapacitated, he could not find work, and spent the next several decades telling passersby that New York summers remind him of Kuwait.

But perhaps it is apt to keep the conversation of amputation in the realm of warfare, for the history of the procedure is the history of battle: Is it a coincidence that the operating room is called a theater? Although we cannot say for sure the extent to which something like implicit biases play into PAD amputation discrepancies, those discrepancies do definitively exist, and they are social, economic, institutional.

In the South Side of Chicago, Chin, Minc, and Peek have spent the last few years laying the groundwork for an integrated, grassroots initiative to improve the quality of provider services and patient self-care among low-income minority diabetic patients. “At the heart of the program is a community education effort meant to teach and encourage members to share in the responsibility of their own health,” says Peek. “But, even as we do see improvements here, there’s a growing diabetes epidemic, our inequitable health care systems persist… I’m hopeful these new policies might change that, but maybe not.”

“Is it possible to spend decades removing parts of people, and emerge whole yourself?”

On floors above and below us in the Beacon, men and women are dying with dead limbs: their hearts seize, give out, or clatter; their kidneys fail; their lungs harden; their brains jam and die for blood; their legs flicker black and flake off like lamp wicks.

A scrub-suited nurse arrives with a cup of something vicious, smelling faintly of fennel, and guides Brunson’s hand, which swipes the air innocently, to it. And when Brunson asks which medication it is, the nurse says it is the one that boosts the rate at which the new lips at his knee will seal.

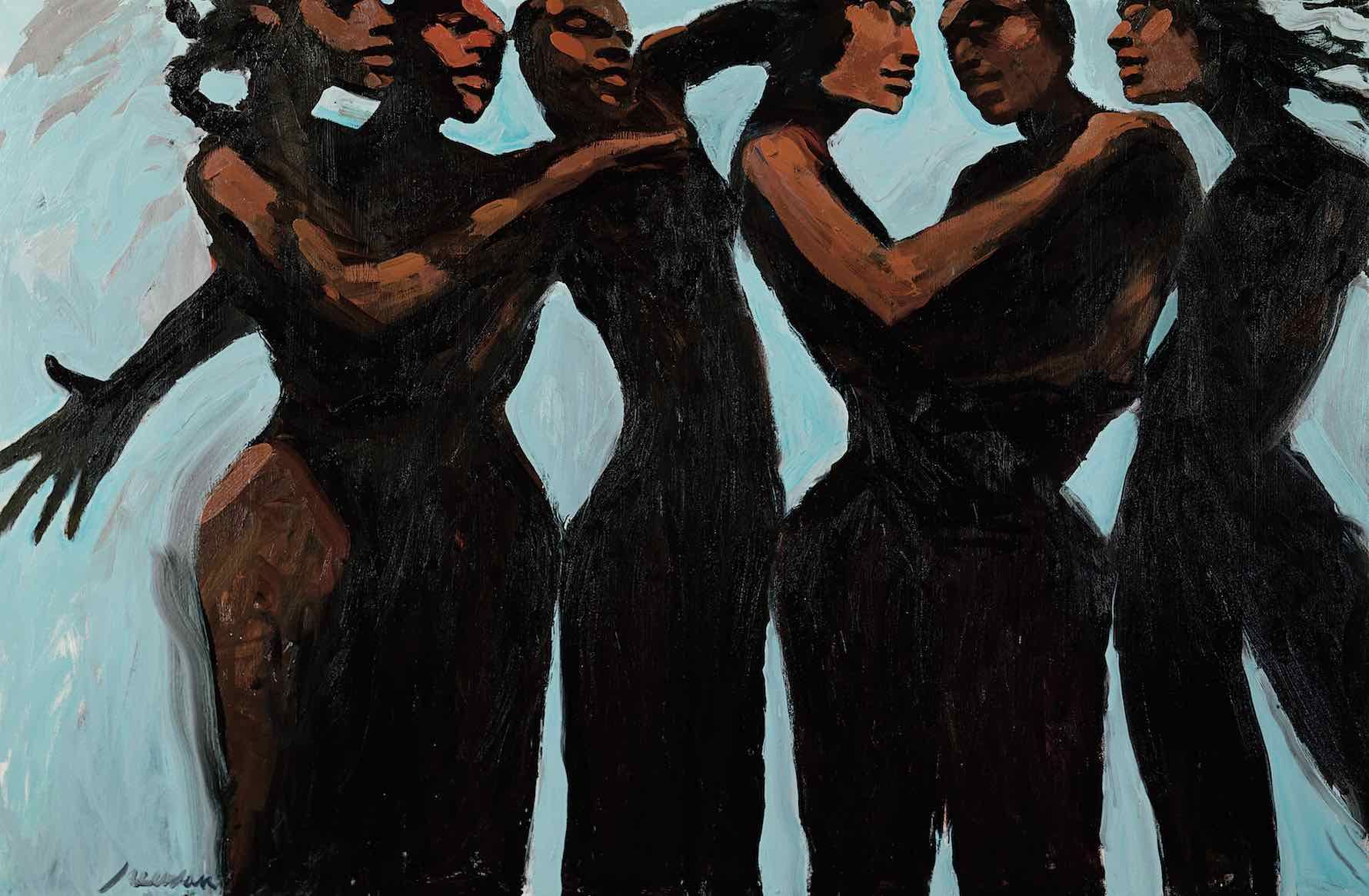

Brunson tells me he’s looking forward to dancing, to showing off every classic move but the waltz. In many cases of PAD, the amputee is too old, too frail to ever use a prosthetic. Many will never walk or dance or spend a day alone again. But Brunson is younger than average, and has muscle and faith. I ask him if there is anything he will really miss. No, not really, he says, “God gives just as much as he takes.” I do not ask if he has realized his inability to achieve the kneeling stance of prayer.