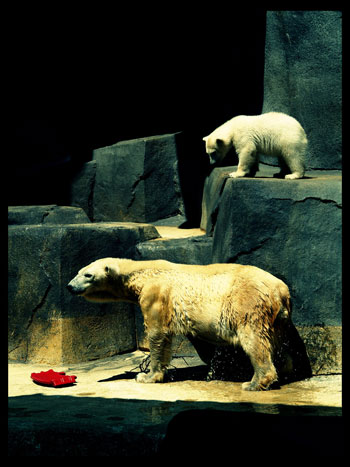

A few months ago I took my daughters to see the bear. The bear was sleeping. My daughters—two and four years old—crouched against the glass and whispered for the bear to wake up so they could share their Cheerios. They were pretty cute. I was less cute, breathing hard in my sweaty gray T-shirt, having pushed the jogger up Lake Michigan to the zoo.

Two boys walked over, and stood on either side of the girls. They were seven or eight. One was wearing a Cubs hat. They started punching the glass.

“Hey bear! Wake up!” Punch, punch. My daughters looked up to me. The boys’ mother stood behind us and didn’t say anything. Punch.

The bear woke, and turned its head.

One boy shrieked.

The other boy laughed, “Ha-ha! He scared you! You were going to run away like a little girl!”

This was not the smartest thing to say around the father of two little girls. A father who’d just gone for a run and was full of testosterone, a father who gets a little unhinged when he perceives any threat to his children.

Take, for instance, the time I kicked the dog.

It happened two years ago. I was carrying my eldest daughter across our local park. I was dribbling a soccer ball. Then I was on the ground, knocked over by an exuberant golden retriever who took out my legs as it chased the ball. I hadn’t seen him coming. Now he was bouncing nearby, the ball between his paws, looking to play. I got up, checked to see that my daughter was okay, walked over to the dog, and kicked it in the gut.

I had a problem with dogs already: Our eldest daughter was bitten by a dog when she was an infant, right at the part in her hair. It required ten stitches. I had been a foot away when the dog bit her and had been too slow to protect her. Sometimes I think the bite may have been more scarring for me, as I was left with the impossible conviction that never again would I let anything bad happen to my daughter.

Even as I kicked the dog in the park, I sort of knew I was kicking the wrong dog. I instantly felt bad. What was I thinking? I didn’t care about the dog, who had scurried off. Or its owner, who was yelling at me. But I cared about what my daughter was witnessing. She saw me kick a dog, and had no idea why.

Was I teaching my daughters that they needed protection? That they were helpless little girls?As I walked home, my explanations fell flat. She stared through me. I thought about how much I loved her, how I’d do anything for her, and yet how my urge to protect her had a way of spiraling off in unintended directions. I resolved to find less destructive ways to express my feelings. Use my words, I thought, and kick fewer animals.

So when the boy at the zoo said what he did, I didn’t kick him. That was a start. It’s not like he was a threat—though that didn’t completely matter. His words cut, and it upset me to think they would make my daughters feel small, angered me to think of all the comments my girls would hear as they grew up just because they were girls.

I looked at the boys and pointed at my daughters, and said, “Are you talking about my girls?”

The boys, seven-year-olds, maybe eight, turned their heads.

“Are you insulting my girls?” I said. I was talking pretty quietly. The boys turned all the way around. The one in the Cubs hat adjusted it to get a better look at me. Their mother was looking at me, too.

“Listen,” I said, not really knowing what was going to come next, “My girls could kick both of your (then I said a word which rhymes with ‘molasses’).”

Oops. That was inelegant. The boys stood up and backed away from the bear, retreating against their mother’s legs as if they had come across something dangerous on a trail. The mother glared at me—this sweaty and hostile stranger—and shepherded her boys away to the safety of the next exhibit.

“Let’s go say hello to the beavers,” she whispered.

As they retreated, I didn’t care. I knew it wasn’t right to threaten children, but what the boy said was wrong. That their mother didn’t say anything was wrong. In the following days, though, I wondered if I’d just found a new and unintended way to screw up. I don’t think my daughters heard what I said—with the bear awake they were more actively trying to feed him Cheerios through the glass—but they could tell I was upset afterwards and that it had involved them.

Was I teaching my daughters that they needed protection? That they were helpless little girls? There are times when parents must stand up for their children, but was I producing exactly the situation I was hoping to prevent?

I also wondered if my impulse to defend my daughters was some unconscious attempt to hold onto my role as their father, to grasp these slipping moments when I’m still strong, still powerful in their eyes. To feel needed before I am no longer needed years from now. I say I want my girls to grow up, to become outspoken strong women, to kick molasses on their own. But once they do, where will that leave me?

As we left the zoo, I didn’t think any of this. I just picked up my daughters, kicking the stroller in front of us as I strode past the boys who were now punching the beavers through their protective glass. And I walked home, one little girl in each arm, holding them as tight as I could.

Being a new father of two girls takes love, patience, and the wisdom not to attack other children in their defense.