When I moved to New York after college, my parents received the news with trembling resignation. They had faith I was a smart, relatively responsible adult, but if they were to believe movies and television—which they did, religiously—New York City was a place where even the smart and relatively responsible are fated to cough their lungs out like Ratso Rizzo, or wake up from a three-day club bender with a crust of dried cocaine in their foreskin and Michael Alig looming over them with a claw hammer and a bone saw.

I had reason to be concerned, too. I was moving with very little cash, no job prospects, and a personal destiny that I had mostly defined in the negative—“Well, I know I don’t want to be a foot doctor,” etc. As a result, I misspent a few years bouncing around various nebulously defined jobs in new media—an industry that was going through a similar identity crisis—before gaining the confidence to begin a career as a freelance writer. (My decision was emboldened by little more than a couple of film reviews I’d written for Time Out and a short feature in a music magazine available exclusively at Sam Goody.)

Modding allowed me to play illegally bootlegged copies of the most popular PlayStation games, plus titles I would never in a million years have otherwise considered playing. (I’m looking at you, Big Bass Fishing.)

My first assignment was writing promotional materials for video games. With all the hours I’d already logged at arcades or at home, with my big toe pressed against the reset button of various game consoles, this job should have been second nature, except for one problem: I’d recently come to the conclusion that games were a great waste of time. Apart from messing around with Myst on my state-of-the-art Pentium 90, and indulging in 10 bored minutes on an Atari 5200 I purchased from a Salvation Army thrift store, I hadn’t really touched a video game since college. I basically skipped over the industry’s bleak period between 1993 and 1996, which was darkened primarily by the Atari Jaguar, Commodore Amiga CD32 and—cue sinister music—Panasonic’s 3-DO, an over-ambitious and over-priced disaster that sold approximately one unit, to the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

It turns out I didn’t need to worry. My writing skills weren’t being tapped to usher in a new golden age of home video games. Instead, I was asked to get kids jazzed about rushed PC adaptations of classic board games like Battleship (“With state-of-the-art animated cutscenes!”) and Othello (“Flip opponent’s chips in real-time! Jaw-dropping motion trails!”). I also wrote online promotions for a Nintendo 64 title where the hero was a white butler’s glove who carried a red rubber ball—tapping directly into the role-playing fantasies of every teenager who ever dreamt of being the Hamburger Helper mascot.

My creative lead for these projects was Steve, a British designer with a textbook Peter Pan complex. Like many other hip British thirtysomething males in the late 1990s, Steve was obsessed with the history of graphic design, rave culture, and electronic gadgets. And when he wasn’t spending his considerable disposable income on mid-century modern furniture or wide-legged denim pants, Steve invested in video games. It was Steve who put a game controller back in my hands, setting me up on the Nintendo 64 that he had claimed for our creative team as a research expense. I guess he noticed the familiar pupil dilation and telltale thumb calluses of a reformed junkie, because Steve quickly moved me on to the hard stuff, coercing me to purchase a Sony PlayStation and then to join his invite-only after-work video game club.

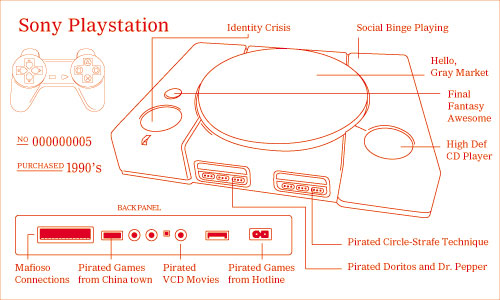

He also introduced me to “modding,” but not in the Burning Man sense of the word. Modding was the gray market, a world of warrantee-voiding hardware chip modification that unlocked a PlayStation’s ability to play games from Japan or Europe. This included my favorite Japanese PlayStation title, Vib Ribbon—a musical rhythm game deemed too quirky to earn a North American release, most likely because of its indecipherable J-pop soundtrack and primitive black-and-white two-dimensional line art. More significantly, modding allowed me to play illegally bootlegged copies of the most popular PlayStation games, plus titles I would never in a million years have otherwise considered playing. (I’m looking at you, Big Bass Fishing.)

Practically overnight I went from video game agnostic to lowlife junkie—creeping around Chinatown with a wad of cash and a Sony PlayStation hidden inside a backpack, looking for someone to perform back-alley surgery on my console. Steve, ever the enabler, furnished me with a hand-drawn map of clandestine bootlegging storefronts, denoting things like “walk up three flights, past the Chinese-language driving school,” “Gundam action figure window display,” and “if you see a guy selling dried eel, you’ve gone too far.” I started hanging around shops with names like “J&T Star Gaming Club,” with signs printed on inkjet paper and Scotch-taped to the door. Their entire inventory existed inside three-ring binders, filled with pages of color-Xeroxed video game box art. Each title was numbered, and you simply pointed to the one you liked. Minutes later, an employee would return with a CD-ROM. These transactions were cash-only, without a register, and completed in near-silence. If the stores were raided—and they often were—they could dismantle their entire operation in about 15 minutes and spring up inside some other rented room formerly occupied by a shiatsu studio or notary public.

These people shined at these parties, eating more Doritos than anyone else, drinking more Dr. Pepper than anyone else, making more uncomfortable innuendos about Lara Croft than anyone else.

Every few weekends, someone—usually Steve—would host a video game party. The outspoken gamers on our creative team would usually attend, as well as a few other co-workers and peripheries I knew only from these gatherings. Two-liter bottles of soda, chips, and pizza were served—sometimes even beer. People would bring their own consoles, multiplayer adapters, and extra game controllers. Once, a guy from the IT department “borrowed” an LCD projector from work, and projected Gran Turismo 2 six feet high on the wall. Steve would often bring a CD wallet bursting with bootlegged games that would get slapped into the PSX, played for about five minutes, then tossed away and forgotten.

For some, this hyperactive consumption was a genuinely social way of experiencing an activity they would otherwise spend hours doing alone, lit only by one of those black halogen torchiere floor lamps that were legally required in all first-time apartments. These people shined at these parties, eating more Doritos than anyone else, drinking more Dr. Pepper than anyone else, making more uncomfortable innuendos about Lara Croft than anyone else. Of course, they also dominated the console, and couldn’t resist the urge to provide loud backseat walkthroughs to casual gamers like myself. I found myself withdrawing during these get-togethers, and wondering how it had come to this. I was in my late twenties—the smooth-skinned prime of my life—in one of the most vibrant and compelling cities on the planet. Yet I was spending my evenings in a darkened apartment with a bunch of guys I barely knew, with a man in a fedora screaming in my ear to “circle-strafe the T-Rex!” and going home with raccoon eyes, stinking of nacho cheese and overheated plastic.

Eventually, in true Scarface fashion, Steven overreached. He had set up a bootlegging enterprise with some guys in the IT department. Each member of the video game club would contribute a small amount of cash, and Steve’s nameless reps would burn copies of games for each of us, then distribute them through inter-office mail. Plans were communicated, slightly coded, through the company’s email program.

It wasn’t long before someone’s guilty conscience ratted out the entire operation. Names were named. Scandal swept through the cube farm in hushed tones. Several had their fedoras handed to them and were shown the door. Even those of us who escaped termination were taken aside and soundly reprimanded. I remember shoving my tail between my legs as I was told, “As your human resources director, I really expected more from you.” It was like being discovered drunk and unconscious in one of the company bathroom stalls. (This actually did happen to another employee in the company, and struck me as a much more interesting way to lose one’s job.)

After the fallout, the video game club unofficially disbanded and rarely, if ever, was mentioned again. It had become a secret we silently agreed to lock inside, like our own G-rated Mystic River. And though I was only a supporting player, I felt truly ashamed of my involvement, mostly because it seemed to fulfill my parents’ dark prophecy. Just as they feared, New York had corrupted me. I was consorting with criminal elements. Even worse, I was consorting with guys who probably masturbated to Japanese tentacle porn. I couldn’t go home and I couldn’t turn back. My hands were dirty—actually, my hands were mostly greasy from pepperoni and wings, and sweaty from sharing a PlayStation controller—and now, maybe, someday a real rain would come and wash the scum like me off the street. Until then, there was always Parappa the Rapper, which I purchased legally, and played alone.