Martha Wilson is a feminist artist, whose photographs, videos, and performances explore female subjectivity and gender performance through physical transformations—using make-up, costumes, and sometimes digital manipulation.

She is also the founder and director of Franklin Furnace, a 30-year-old organization that promotes multi-media experiments in the arts while simultaneously working to preserve artists’ books and event records. I spoke with her recently about the concepts behind pieces in her latest show and the state of performance art in the US.

Wilson’s latest exhibit “Mona/Marcel/Marge” will be on display at the P.P.O.W. gallery until Dec. 22, 2015.

Your face and body are central to your work. Do you view the body mostly as a canvas or is it also a source of inspiration for you?

I think I started out not so much with the body but with the brain. I was interested in the internal landscape and how it could be affected by putting your body into different situations. For example, in 1972, I dressed as a man trying to dress as a woman, so it’s a double sex transformation from female to male and then back into female, because I wanted to know what it felt like to be a man trying to look like a woman. The result of that experiment was a photograph that had me wearing a wig, false eyelashes, false fingernails—you know, everything that a man would need to convince the world that he’s actually a girl. So, although you have to live in your body, like I said, I started with the brain first, with the experiential view, using performance art as a way to gain understanding.

“A result of the experiment” makes it sound secondary to the “experiment.” Do you view it that way?

The photo’s the proof. You have to accept that I did the experiment when you see the photo, but really the performance is for the audience of one, in other words, for the self.

The show’s title comes from a photograph in which you’ve put a Marge Simpson wig and necklace on the Mona Lisa as reimagined by Marcel Duchamp (i.e., with a moustache). What were you thinking when you put those pieces together?

I thought it was a piece about the layers of recognition: the first thing you see is the Mona Lisa, the second thing you see is Marge Simpson’s hair, and the third thing you see is that it’s Martha Wilson’s face in the middle. But my friend Britta Wheeler, who’s a performance artist and sociologist, said, “No, no, Martha, it’s a portrait of post-modernism—because the Mona Lisa is the highest of high art, Marge Simpson is the lowest of low art, and Martha’s in the middle.”

I did the Mona/Martha/Marge piece for my show in 2011, then, for this piece, I added the Mona/Marcel/Marge image and made it into a lenticular photograph—meaning if you look at it from this angle you can see the Mona/Marcel/Marge (it has a moustache), and if you look at it from that angle, it says Mona/Martha/Marge (without the moustache). It’s like postcards you get in Germany showing the cathedral after it was bombed and then after it was restored kind of thing.

But why make it a lenticular?

So I can have it both ways.

One thing that struck me in this show was the prominence of the frames: often, especially online, the art is presented just as the image, without the frame.

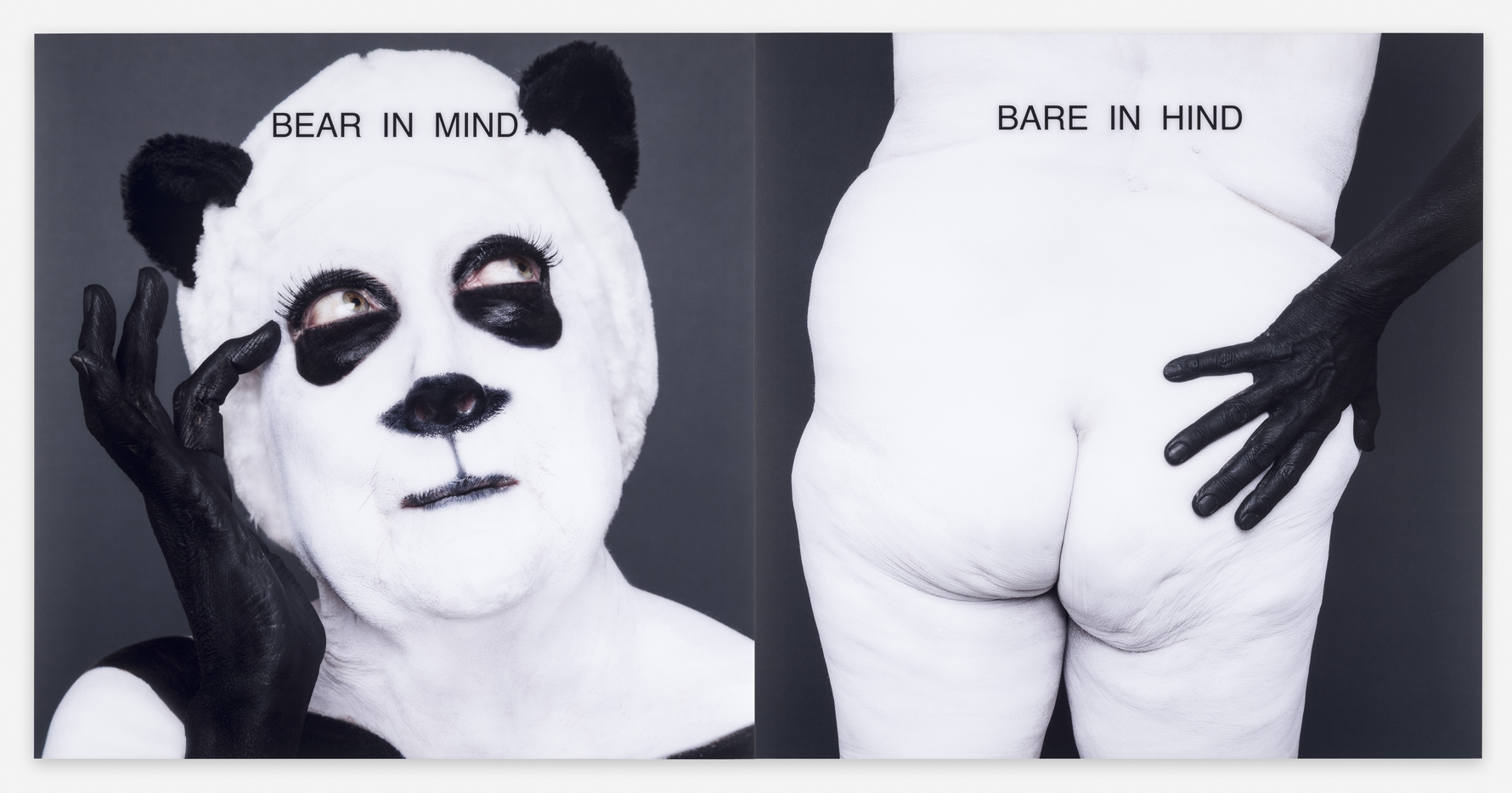

For this show, I’m having fun with frames. “Bear in Mind/Bare in Hind” has no frame, but it’s giant—it’s 48x48 inches. And each image has 1/16th of an inch of plexi-glass over it so that the photograph’s protected from handprints and passerbys’ elbows. I thought about each work and how I wanted each work to operate in relation to the audience and ended up framing them pretty differently. The one that’s an homage to Ad [Reinhart], I framed it up like the image that’s in the current show at the Whitney. “Mona/Marcel/Marge” has an antique frame that I bought online and had cut down for the image. Each time somebody buys that we’re going to buy a new frame, so each one will be slightly different. Basically, if it’s in a simple frame, it’s because the text is what I want you to focus on, and if it’s an elaborate frame, I want the whole image to be considered, including the frame.

If you are looking at the works online, you don’t see the color of the wall behind “Mona/Marcel/Marge,” which is red, and the color of the wall behind “Martha Meets Michelle Halfway” is blue, and then the color of wall behind “I’m Going to Die” is black. We painted sections of the wall to take you to the Louvre Museum or take you to Washington, DC, within the gallery.

In a similar vein, your titles take a prominent role. Why put the text on (or right below) the image?

Because the title and the image work together. They comprise the piece together. It’s not an image that I want you to consider without consideration also of the conceptual angle that I’m coming from.

Would you consider yourself primarily a performance artist?

The way I approach it is to define performance art as a spectrum of things. It could be a photograph and a text documenting an experiment, or it could be a live performance in front of people sitting in chairs, or it could be a video of an event that I did for the benefit of the video camera. All of those things I think are part of the feminist and performance art discourse and so I don’t really make a distinction. I do like the term “performance artist,” but “artist” is fine as well.

How would you sum up the state of performance art in the US (or New York City) right now?

We used to have more venues, and, in the ’70s, performance art was the hippest thing around, so the US government was providing grants for travel and performance and collaboration. Then Ronald Reagan was elected and performance art just became the virus eating away at the health of the body politic. Performance artists themselves like Karen Finley got death threats and had to mount a lawsuit against the US government just to get the grants they’d already been given by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Today, in spite of the fact that there’s very little support, performance art is alive and well all over the country.

Later the government killed off the grant program period, thinking that they could put performance artists out of business, that performance art would somehow go away. What really happened was that the artists went outside and they went online—they went to the wider, unwitting audience instead of just the people sitting on folding chairs in the basement of Franklin Furnace. They went out into the world, which has the opposite effect than the legislators wanted.

And today, in spite of the fact that there’s very little support, performance art is alive and well all over the country.

You’ve done performances as a number of the First Ladies, most recently as Michelle Obama. Can you talk about how you navigated the difficulties of portraying a non-white First Lady, as a white woman?

The backstory: Joe Melillo asked me to be a curator for the BAM Mixed Wave Festival for Performance Art, so I selected three artists to perform in October 2014, one of whom was Clifford Owens. Owens is African-American and he’s known for creating forums where performance art itself is discussed between the artist and the audience. He, Clifford Owens, turned around and invited me, Martha Wilson, to be Michelle Obama.

I freaked out and then asked Saya Woolfalk, a black woman performance artist, what I should do, and she said, “You should refuse the invitation.” Then I asked Lorraine O’Grady, another black woman performance artist, what I should do, and she said, “Well, you can perform, but you have to perform in your own skin.” I asked Clifford if he would apply make-up to me, and he said, “I’m going to be busy being the emcee, I can’t really do that.”

So in the end of a long and agonizing thought process, I hired a black woman make-up artist to make up half of my face as Michelle, and she was quite intent on getting the shade exactly right. Then, when I got to the performance at BAM, I didn’t just walk out as half Michelle: I showed images of 30 years of impersonating First and Second Ladies (Nancy Reagan, Barbara Bush, Tipper Gore) to show the audience that Clifford had invited me to do this because I’d been doing this a long time.

When I came out, I had to explain to the audience that I’ve always satirized these women, but that I have nothing but praise for Michelle Obama. I approve of organic gardening in the back of the White House and think she’s being a wonderful First Lady. Clifford turned to the audience for comments and Elizabeth Weatherford, whom I know, said, “You know, Martha, if you were Michelle, you would own the room: you would look straight into people’s eyes, you’d be relaxed and in charge instead of looking like you’re pretty sure somebody’s going to throw tomatoes.” Which was how I felt.

What was the first piece of art you ever sold?

Oh, easy. It was called “Breasts Forms Permutated,” in 1972. It was a grid of breasts—flat-chested in the upper left-hand corner, full-breasted in the lower right-hand corner, perfect set in the middle. I sold it for $150 to Ian Murray who lives in Toronto. To me it was a spoof of the work of Sol LeWitt and the conceptual artists of the ’70s, who were busy “permutating” everything. I decided to pick something that could never be thoroughly permutated and described, because everybody’s boobs are gonna be different.

I was annoyed that the conceptual artists of the day were not engaging with stuff that actually mattered to life. And I think that’s where the post-modernists interfaced with the conceptualists and started to gravitate toward what’s now called “social practice,” where the art has some effect in the world, is related in some way, is engaged with the world around it, instead of being so separate.