IH8YRST8

Studying drivers across the country for signs of license-plate prejudice—or, why everyone loves Vermont drivers and hates Texans.

I learned something new when we moved back to Colorado from Texas last year: People who live so far above sea level have razor-edged opinions about outsiders.

While I procrastinated for weeks in getting new license plates, drivers wouldn’t let me change lanes—sometimes informing me of their refusal with their middle fingers—one even gleefully made the Longhorns hand gesture when he cut me off.

I swear, I am a classically trained defensive driver. It wasn’t my driving. It was my Texas plates.

The prejudices that arise when drivers encounter different state license plates are largely unstudied. This is unfortunate because, according to my field research, they play a role in determining driver behavior and they reinforce stereotypes many drivers didn’t even realize they held.

For example, Coloradans’ dislike for Texans might be explained by the fact that they’re moving here. According to the Census Bureau, 24,431 people who lived in Texas in 2013 had listed Colorado as their place of residence a year later, versus the 18,277 Coloradans moving to Texas in that same period.

But Bill Marvel explained in a 2008 article for Denver’s 5280 magazine, “Don’t Mess With Colorado,” that the state’s hatred for all things Texas could be as ancient as the latter’s 19th-century “territorial ambitions.” Or that it might be the result of the real-life versions of The Simpsons’ Rich Texan who move north and mess with Coloradans’ livestock and screw over skiers and hikers by privatizing trails. Or maybe it’s simply a reaction to Texans like Walter Cliff of Amarillo, who was so pissed when he couldn’t find a Bud Light on his Colorado vacation in 2012 that he wrote a letter to the editor of the Durango Herald: “Heads up, Durango, not everyone likes that locally brewed beer.”

And that’s not even counting the “gapers,” Texans and everyone else who drive tens of miles under the speed limit while drooling over the site of Colorado’s glorious mountains. New Englanders have their own version of this in the fall: the leaf peepers.

Brian, a California resident from Wisconsin, said when he sees a license plate from the Badger State he assumes the driver is “most likely drunk.”

Whatever the reasons, and there are many, license plate prejudice is not unique to any one area of the country. And it’s likely not new. While the term “Masshole,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary, has only been in regular use since 1989, it’s hard to imagine that it hasn’t been in effect since the first official license plate in the country was put on Frederick Tutor’s car in 1903—in Massachusetts.

To get a sense of which plates incite hatred (and happy thoughts), I surveyed and spoke with more than 50 drivers from 31 states, a small but opinionated and talkative sample size. Including one man from Vermont who, when just looking at a Massachusetts plate, wrote that he “fully expects Massholic behavior from you, you Masshole.”

But let’s start with the less pissed off among the respondents. It’ll be quick.

Home Is Where I Used to Live

Twenty drivers I heard from were happy to see plates from their home states, from which they overwhelmingly had moved away. Only five still lived in (or had moved back to) their home states of Wyoming, Texas, New York, and Colorado.

For instance, Vincent, who is from New Jersey and lives in Texas, said he has no allegiance to his home state, yet he feels an “unspoken bond” with drivers sporting Garden State plates. He explained, however, that when he encounters them in person, their exchange usually begins and ends with the driver asking, “You’re from Jersey? Which exit?!” This isn’t his favorite question. “Everyone thinks they’re the first person to ask it and because the part of Jersey I’m from is south of the Turnpike, there are no exits. It is basically Kentucky.”

Kelly, who is from Illinois and now lives in California, said if someone driving with her home state’s plates behaved impolitely on the road, they’d get a pass because: “Aw, my home state! Forgiven!”

Carrie, who used to live in Illinois, would have a different reaction: She’d shout “FIB!” For those who don’t know, “FIB” means “Fucking Illinois Bastard.” And Carrie thinks it’s hilarious.

As someone from the Finger Lakes of New York, who hasn’t lived there in more than a decade but feels similarly, I call this “nostalgia creep.” As the years pass and we move farther and farther away, the more those license plates represent faded Polaroid photos we look upon fondly.

Not everyone suffers from the creep. A selective few had less friendly reactions when reminded of where they’re from, like Brian, a California resident from Wisconsin, who said when he sees a license plate from the Badger State he assumes the driver is “most likely drunk.” The state does rank eighth highest for DUI arrests, so maybe he’s not that far off.

Then there’s Alex, who lives in Colorado and saved most of his vitriol for his native South Carolina plates: “Can’t help but have a certain biased disregard for my own home state that (since its first appearance in the nation, practically) runs itself backward against the rest of the nation.”

Alex’s home state does offer a license plate that honors Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune, a woman who you most likely don’t know but should. She is the first African American to be honored on a South Carolina plate, which has been on sale since 2013. Of course, since 1999, the state has also issued license plates with Confederate flags, which Politico reports raises $20,000 for the Sons of Confederate Veterans every two years.

Everybody Hates the South

It should be of no surprise that respondents blanketed entire areas of the country with their derision. I should point out that drivers from the East and West Coasts and the Midwest offered apologies for their biases against “damn Southerners,” as one New Yorker referred to them. And they didn’t like the ways they personally rushed to judgment, though that didn’t stop them from doing it. M. from Washington said if she saw a Southern plate her prejudices “would flare … that Republican!” but that she recognized that it was “totally unfair” and her reaction was “often contradicted by [her] actual life experiences.”

Another New Yorker felt guilty for the special and “certainly unjustifiable” dislike he would feel for an aggressive driver with Texas plates—especially since he’d never visited the state.

There also seemed to be some cognitive dissonance for drivers from New York, Wisconsin, and Colorado, who specifically referred to drivers from the South as “rednecks” and “hicks”—a classification of people, I’d point out, not geographically limited to one area of the country.

One driver from Wyoming, who didn’t want to be named, wrote that a Southern plate probably meant the driver was “not good driving in the snow” and that, while he hated admitting it, he would “wonder if they are racist.” Monique, who’s from Oregon and lives in Colorado, gave Southerners some backhanded benefit of the doubt, because “maybe they’re smart and have to live in that state below the Mason-Dixon line.”

It wasn’t just Southerners who inspired dislike. Drivers from Minnesota, Nebraska, and Kansas reported that cars with Iowa plates were known by many as “Idiots Out Wandering Around.” Michael from Texas jokingly wondered if they weren’t bad drivers because they were in a “hurry to hear the latest Donald Trump speech?”

This survey was taken before Ben Carson took over the state’s polls; it’s anyone’s guess whether that’s better or worse. The kind of Midwestern nice that many associate with Dr. Carson may or may not apply to all Michiganders, like the one who said she “might have a slight prejudice against East Coasters (that they are snobbier/less friendly).”

Nearly half of all respondents mentioned a state’s politics as a reason why some plates piss them off.

While over half of respondents reported negative thoughts about Texas and other Southern states, drivers from New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts were called out over and over again (almost as often as Texans) for their rude, aggressive, and asshole ways. Which isn’t surprising, in fact: All three states ranked in the top 10 rudest drivers in America, according to a 2014 Insure.com survey of 2,000 drivers. It should be noted that no Southern state made the list and no respondent I heard from cited rudeness as a reason why they hated spotting plates from Alabama, Florida, and other Southern states.

Jennifer from Missouri said she sometimes assumed drivers with Eastern plates were “hurried capitalists.” And maybe they are, but they’re also quick to judge each other. Especially if, at least from the people I talked to, the car ahead of theirs has Pennsylvania plates—referred to by Vincent from New Jersey as “one of the most unpleasant states in the Union.”

Tiffany from Jersey added a new word to my vocabulary: “Shoobies.” As she explains, it means: “People who live out of state and travel to every Jersey shore point every weekend/holiday of the summer.” She applauded the drivers on their vacation-taking with a (sarcastic) “Good for you!” but said they were obstructing her commute to work. At the end of the day, “Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New York plates on the weekend will automatically, no matter what kind of day [she’s] having, evoke a hateful feeling.”

While out-of-state plates represent, for many, temporarily clogged highways when the Aspens turn golden or when summer vacation finally kicks in, there’s often more to the story. In some parts of the country, they represent competition for jobs and higher rents and housing prices. And in others, suspicion of undocumented immigrants. Another Jersey driver, who wished to remain anonymous, said that it’s easier to get plates in Pennsylvania because you don’t need a social security number. Apparently some from Jersey assume drivers with PA plates are not in the country legally and they expect them to flee the scene of an accident.

Erik, who is from Texas and lives in Virginia, cares about where drivers with PA plates are from for a different reason: “On the off-chance they’re from Philly—many shitty people on the East Coast are.”

To put this in perspective though, Erik hates a lot of drivers. He said those from Maryland will “fucking cut you” and had a surprising critique for drivers from the Blue Hen State: “Delaware pretends to be simple and friendly, though the entire state exists to exact rents from the rest of the country through toll roads in strategic locations necessary for East Coast transit,” and he also disliked their “state court domination of corporate law.”

While it’d be difficult to find another, similarly specific take on the state, Delaware—which has fewer people than the city of San Jose—was mentioned negatively by drivers from across the country.

Using data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, a car-insurance comparison website ranked Delaware in the top three worst states for speeding, drunk driving, and careless driving. Which maybe validates Dave, who’s from thousands of miles away (Washington) and lives in Illinois, and warned: “Never initiate any kind of speed race with someone from the ‘First State.’ They have a chip on their collective shoulder.” While he didn’t explain further, could it perhaps be linked to the reason why Cory from Oregon mentioned the state as well? He said it reminds him of Wayne’s World.

License Plates as Historical Triggers

While many respondents mentioned well-known stereotypes about certain states— Massholes are Massholes, New Yorkers are pushy, Texans are cowboys who think they own the road, drivers from New Mexico are hippies—some dug a little deeper.

William from Kansas jokingly summed up his biases against cars with plates from New Jersey (“Snooki”) and Florida (“Alligator Rapists”) but his complaint about Missouri was more serious: “William Quantrill.”

Quantrill was a gambling, horse-thieving murderer, who, as a Confederate captain based in Missouri, led the Lawrence Massacre of 1863, where 183 men and children were killed, the Confederates “dragging some from their homes to murder them in front of their families, and [setting] the torch to much of [Lawrence, Kan.].”

William’s knowledge of history also played into his reaction to a Mississippi license plate. “I know what ‘Forrest’ means, Mississippi,” William wrote. “You disgust me.”

Mississippi, as William’s response addresses, puts county names on its plates. Forrest County, Miss., is named after the Confederate Calvary general, Nathan Bedford Forrest. As Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote in the Atlantic, “[Forrest] made his money buying and selling people… and when the war started he dutifully enforced the Confederate policy of giving no quarter to black soldiers. At Fort Pillow he massacred black soldiers trying to surrender, and afterward went on to found the Ku Klux Klan.”

Intra-State Intolerance

To take a step back, 13 states’ plates reveal where the driver is from—either by listing the county on the plate or by using a series of numbers or letters particular to certain counties.

Plates registered in Macon County, Ala., for instance, begin with the number 46. The DMV in that county, however, where 82.6 percent of residents are black, was previously only open on Wednesdays and is now closed—in a state that requires a photo ID to vote.

Joel, who is from Mississippi, said the county names on the state’s license plates reveal to residents which drivers are from a coastal county and if they are, whether they’re “trashy (Rankin), super rich (Madison), etc.” Drivers with plates from Madison were, Joel said, from “East Dillon” (Friday Night Lights fans will get it), while cars with plates from Rankin represented the part of the state known for “meth and tornadoes.”

During the civil rights movement, the county name on a license plate could put someone’s life in danger.

In her memoir, For Us, the Living, Myrlie Louise Evers-Williams, wife of the civil rights activist Medgar Evers, writes that, after the death of Emmett Till, her husband and others disguised themselves as they went to investigate—including using a car with plates specifically from a Delta county, not the county where Evers lived—so they wouldn’t arouse suspicions.

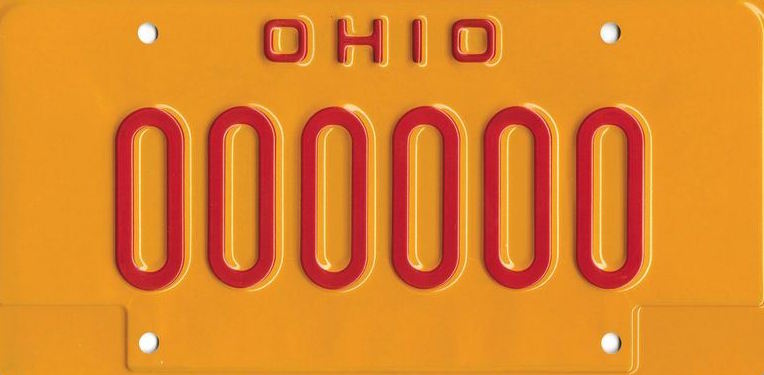

And while no one mentioned it, not even Marty from Michigan, who admitted that “most Michiganders have negative thoughts about Ohio,” I’d be remiss in not pointing out that the state of Ohio has gone out of its way to draw its residents’ attention to a certain style of yellow plate—ones required of drivers who are DUI offenders.

Some Ohioans view these as scarlet letters. I’d mention how much it must suck if the plates are on a shared car, or that they might serve as a flimsy excuse for probable cause even if the driver isn’t doing anything wrong. But many Buckeyes apparently refer to them as “Party Plates.” One Redditor even claimed in a “Today I Learned” post about the plates that a bar in her hometown offers free drinks for those who turn them in when they expire.

Plate Hate Realpolitik

The generic stereotypes held by the people I spoke with represent more than just an echo chamber. Nearly half of all respondents mentioned a state’s politics as a reason why some plates pissed them off.

Liberals from Colorado said plates from Nebraska, Oklahoma, and North Dakota would make them “mumble something about the selfish nature of Republicans,” Indiana plates represented Republican bastards, and Wyoming is the “fucking Dick Cheney state.”

Another liberal who lives in Florida said when she saw an Arizona plate, she wondered “Why don’t you pay more taxes to support public education?” She was more direct when she mentioned that her extended family is from Wisconsin and that their plates make her think of “asshole Republicans.” Bonnie from Washington expanded on Hannah’s Badger diss: “Wisconsin will always get the Scott Walker rant. He’s a jerk and so is his state.”

It’s worth pondering whether the fact that we’re one Halloween away from a general election heightened respondents’ reactions.

In another very specific response, a New Yorker said he expected drivers from Alabama, West Virginia, and Tennessee to be conservative and have family members that fly the Confederate flag (to which he said “Sorry!!”), and that if a Kentucky plate passed him in New York, he’d assume they were “probably headed to a Kim Davis rally #praisejesus.”

On the other side of the spectrum, when Marty from Michigan saw a vanity plate, regardless of the state, that indicated its driver was a Democrat—or even if it just started with the letters DEM—she said her reaction would be simply that “she didn’t share their political stand.”

Finally there was Ray, who was raised in Louisiana: “Texas drivers have this weird Republican sense of entitlement combined with Tea Party rage. Fuck Texas. I’m surrounded by Texas plates and they remind me every day that I’m still stuck in fucking Texas.”

Fucking Texas

You knew we were working our way to it. In 2013 Business Insider asked 1,603 survey respondents which state was their least favorite, and, probably not to Ray’s surprise, they answered: Texas.

This is where I’ll interject that as a former resident, I don’t really understand the hate. Yes, everything goes to hell if there’s a hard freeze, and how many times do you have to hear “Don’t Drown Turn Around” before you actually do it, Austinites? But Texas drivers also create and make full use of “courtesy lanes,” where you drive in the shoulder for a quick second so someone can pass you, a move I wish more Coloradans would adopt.

Alas, very few I spoke with were willing to give my former neighbors any slack. Another Louisianan, Josh, said that when he sees a plate from the Lone Star State he always yells: “GO BACK TO TEXAS”

Stephanie, who considers Delaware and Pennsylvania home, now lives in Texas and thinks its drivers act “like they own the road and don’t feel they have to play by the same rules.” And Katie, who is from Colorado and lives in California, concurred, writing that Texas plates reflect drivers who think they’re “above the law; cowboy does what they want!”

Drivers from both New York and Washington assumed that Texans “doing what they want” included wearing cowboy boots and 10-gallon hats, but also having a gun in the car. Regardless of how she feels about the state, Washington Bonnie said she wouldn’t mess with anyone with a Texas plate because “I always suspect they’re packing.”

Still, the bravado of Texans can be kind of fun. Dan Solomon reported in Texas Monthly that the state’s DMV was auctioning off “rare two-character” plates. And because apparently the Patty and Selmas at the agency weren’t fluent in text-speak, they offered this specific plate:

Which, honestly, would’ve been amazing. Except someone apparently told them what it meant, and they pulled it soon after.

Texans seem to get off on their reputation as the least-liked state, But what do they think about plates from other states? In an unscientific list called “State Hate” posted on Deadspin in 2014, Texas’s enemies were: “Everyone.”

So maybe it’s unsurprising that Jennifer, who is from Texas, called nearly every driver with a plate from any other state a “friggin’ foreigner.”

Among those she disliked, she said Mississippi and Louisiana had no “Southern respect,” but it was Alabama that pissed her off most. When I asked why, she said she had a few high school friends on Facebook who were always posting “Roll Tiiiiide!” She explained why this was problematic: “GIG ‘EM WHOOP!” For those who don’t know the reference, Jennifer went to Texas A&M.

There was, however, one state that didn’t raise her ire: If she saw a plate from Alaska on a Texas highway, she said: “Let them blaze the trail and follow behind.”

It’s not the State, It’s the Plate

While vanity plates deserve (or don’t) an article all to themselves, the design of an official plate was more of a concern to some drivers than where it was from. Take Mary, from Texas, who said that she would “probably think [anyone with a Confederate flag] on his plate was “a redneck.”

She’s less likely to see those plates on the road, thanks to a recent Supreme Court decision, which concluded that states can refuse to issue special license plates with the flags. Virginia and Maryland have stopped selling them. But some states still do, like North Carolina—and neither the governor nor the state legislature has made any move to bar the plates.

Hopefully they will. In Pacific Standard, Tom Jacobs reported on a study published in Political Psychology that showed the plates may “provoke discrimination” and that “the study suggests exposure to the Confederate flag triggers unconscious attitudes of racial bias in white Americans—including those who believe they are free of prejudice.”

Some drivers noted that special license plates provoke not their hatred but their respect. Michael from Texas said that he was most likely to have a reaction to plates that indicated the driver has a Purple Heart or was a prisoner of war and that regardless of the state: “They can do no wrong, and they should feel free to cut me off if they want.” Amber from Colorado said similarly: “I do keep a look out for Vet plates and firefighter plates and give them the respect they deserve.”

Even When They Don’t Feel the Bern, They Love Vermont

Ella, Billie, Frank, and Willie have sung of their love for the “Moonlight in Vermont,” and many drivers I heard from seemed to be particularly enamored of the state.

Lindsay from New York said that she has “a romantic view” of the state: “Their plates are pretty, and I always wonder about the person driving the car.” Other New Yorkers, like Melissa, said: “When I see a plate from Vermont it always triggers a thought on what it would have been like if I had moved there instead of my current location.” And Pam said they make her think of “ski vacations and maple syrup.”

Nina, who is from Wyoming, wrote that she thought those with plates from the Green Mountain state were most likely “hearty and wholesome.” Georgia George said “If all states could be like Vermont, we’d all be in a better place.” And Greta from Colorado summed up her views succinctly: “I like those people.”

These responses conflicted with the Insure.com survey on rude drivers, where Vermont was ranked the third rudest. Citing a study by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the authors of the poll said “Vermont ranked No. 1 in the greatest increase in fatalities per distance driven of any state” between 2005 and 2012. They’re also apparently notoriously fast drivers. When the police department in Brighton Vermont put up one of those signs showing each driver’s speed, it was stolen before it could be insured.

Pride and Prejudice

It’s difficult to come to a conclusion about what drives license-plate prejudice. On Long Island and in Connecticut, out-of-state plates are a sign of cheaters who register their cars elsewhere because it’s so expensive in their home states.

And then there’s sports. I love Texas, but there’s no one I would be less likely to let into my lane on the highway than someone with a Dallas Cowboys plate. So I have more in common with Jennifer than I would’ve thought. As someone who loved to play the license-plate game in the backseat of my family’s station wagon on vacations, I didn’t realize, until writing this, how much I’ve changed.

While my Texas plate may have made me a target in Colorado, I can’t say the experience made me more empathetic to out-of-state drivers. Commuting home on a busy Denver boulevard recently, I found myself irrationally annoyed by the Oregon driver ahead of me, puttering well below the speed limit. Before I realized what I was doing, I yelled at my windshield, “POT IS FINALLY LEGAL IN YOUR STATE, GO HOME.”