On the flight from Bombay to Zurich there is a crying baby. This baby cries for the entire nine-hour flight. Its cries are desperate, wailing, pained, ignored. At first I try to sympathize, but when I catch sight of the baby on my way to the bathroom, it becomes impossible. It is an ugly, despicable baby. While I pee, my only feelings for this baby are hatred. An entire airplane full of people wants to sleep, but because of the baby they cannot. An entire airplane full of people hates this baby. Of course the baby has no idea of this, while the mother, I realize on my way back down the aisle, with her sari unraveling, hair disheveled and make-up smeared, looks far more fed up than anyone else.

In my seat, I realize that sleep isn’t going to happen, so I tuck into the book I’ve bought for the flight home: Tomorrow’s India: Another Tryst With Destiny, a collection of essays edited by B.G. Verghese. Having failed to make any real insights on my own during my trip, my hope is that some of the country’s preeminent thinkers will provide them for me.

With the baby’s shrieks ringing in my ears, I’m pleased (even proud) to discover that one of the first essays in the book echoes some of my own impressions. In a piece entitled, “India 2025: Illusions, Realities, Dreams,” Deepak Nayar describes his homeland optimistically, “The country which only had a past is beginning to be seen as a country with a future,” but then goes on to lament the fading sense of history among Indians intent on becoming part of the new boom.

A number of the other essays adopt a similar tone, often with a nostalgic idealism for what the writers imagine is being lost in, as Gopalkrishna Gandhi describes it, India’s “ruthless lurch towards self-advancement and self-aggrandizement.” As I read more, the baby still hollering away, Tomorrow’s India paints a portrait of a country suffering from a sort of convenient, collective amnesia, reminding me of V.S. Naipaul’s critique, made decades ago: “In seeking to rise, India has undone itself.”

When we arrive in Zurich everyone takes a moment to glare at the offending baby and its mother as they disembark. She looks apologetic. I feel bad for her, but this passes when, joy of joys, I discover the same mother and baby (still crying), at the gate for my connecting flight to Toronto. They are heading to Canada, where I imagine this poor woman pushing her obnoxious, wailing kid strapped in a stroller around grocery stores, down sidewalks, into Lake Ontario.

In the plane, when the automated safety instructions come on, they sound frustrated—as though they’re struggling to be heard over the crying baby, as though they remember it from the last flight and are thinking, like me, “Oh, fucking Christ. Here we go again.” When they suggest storing personal belongings in the overhead compartments, I wonder if this could include things other than luggage.

The flight takes off and I get reading again. Tomorrow’s India explores everything from social activism, which the amazingly named Harsh Mander claims “needs to reinvent itself” in the new me-first India, to a treatise on reality shows by Sagarika Ghose: “[They] have swept up thousands of viewers, finding a ready echo in a mass-aspiration society on the cusp of economic liberalization.” The book, as a whole, provides an interesting, thoughtful, provoking and thorough look at how India is negotiating its transition from the third world to world power.

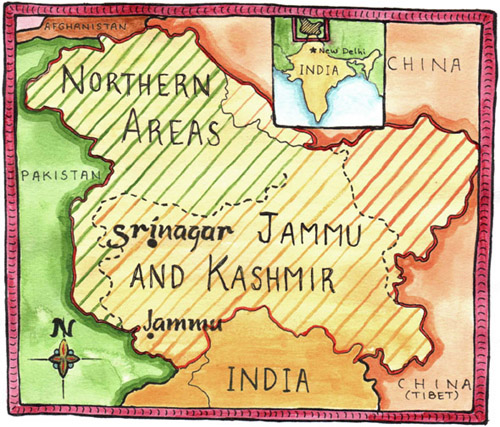

There’s no sight of land, just the ocean sprawled out beneath a few puffs of cloud below. India is an entire continent away. Where this leaves Kashmir, however, remains a mystery. There’s very little discussion in any of the essays about arguably the most important political and diplomatic issue facing South Asia today. I have to wonder if people aren’t starting to turn their back on the whole business, if it’s seen as a lost cause rooted in a past that might lack contemporary relevance.

No one in my family has spent much time in Kashmir in nearly 20 years; that I, a non-Kashmiri-speaking Canadian, am the last Malla to carry on the family name speaks volumes about how Kashmiri Pandit identity is undergoing a slow decay over generations. If the place is historically, culturally, and physically lost to its own people, why should young Indians from Delhi, Bangalore or Mumbai caught up in the country’s steady gallop into the future care? As I finish Tomorrow’s India, I realize that I’m still lacking answers to my most pressing questions, and the baby’s unrelenting screams seem to mock me from four rows up.

I close the book and look out the window of the plane for the first time since before take-off. We’re already way out over the Atlantic. There’s no sight of land, just the ocean sprawled out beneath a few puffs of cloud below. India is an entire continent away.

I close my eyes, listening to the baby’s screams reach a fever pitch. What could anyone ever have so much to cry about? What does this kid know that I don’t? Then, like a radio being snapped off, the screaming stops. There is only the dull roar of the plane, coasting along 30,000 feet into the sky. It is, without doubt, the most beautiful sound I’ve ever heard in my life.

The plane flies along so smoothly that, with my eyes closed, it feels as though we could still be on the ground—rumbling there on the tarmac, waiting to be cleared for take-off. I could be waking up from a dream about leaving, and we could still be in Bombay; or waking up from a long sleep, and we could already be back in Toronto. I actually have to open my eyes to ensure that we are really flying, but even then the water below, nameless and blue and everywhere, provides no bearings. It could be the Arabian Sea or one of the Great Lakes. Crossing datelines either way, it could be today; it could be tomorrow. It could be whenever, and I could be wherever: home or away, in Canada or India—or some place, any place, in between.