“Find me a Twins fan to fight,” I tell my friend Alisa, the type of Yankees enthusiast who bleeds pinstripes, during the top or the bottom of the fifth. Or is it the sixth?

She laughs. “I don’t think you’re going to find any Twins fans in this bar.”

Alisa and I are watching game three of the 2010 American League Division Series at The 51st State Tavern, a dive bar renowned by the nearby George Washington University students for serving cheap wings. I never spent much time here back in the days of beer pong and all-nighters, so it’s a surprise to find a slice of the Big Apple—along with an impressive variety of Stoli flavors—right here on Pennsylvania Avenue NW.

All of a sudden, one of the players hits the ball or strikes out or does whatever necessary to end the game.

Theeeeeeee Yankees win!

The win is more significant than a singular triumph—the New York Yankees have swept the Minnesota Twins in the series. The crowd erupts into Frank Sinatra’s ode to the city that never sleeps. I couldn’t care less.

Instead, I’ve mentally boarded a covered wagon headed out to Minnesota, home to not one but two of my college exes. Their corn-fed hopes and dreams for a World Series title have been crushed. Decimated. Dried out like prairie grass after a dry summer. The thought brings a smile as bright as the unforgiving sun to my face.

This can’t be good, even though it feels…so good. What’s wrong with me?

There’s only one diagnosis. And it’s not even native to my tongue.

Schadenfreude.

The German word schadenfreude is pieced together from two others—freude, the plural of joy, and schaden, the plural of shame or pity. “It’s literally joys that come from sorrows or sufferings,” John Portmann, University of Virginia professor and author of When Bad Things Happen to Other People, tells me when I call him for a second opinion. When I bask in the image of my exes crying into their choice of any of Minnesota’s 10,000 lakes, I’m experiencing some serious schadenfreude.

What I find interesting is that no such word or phrase exists in American English. (Whether the word “epicaricacy,” which has Greek roots, qualifies is subject to debate.) Certainly, there is no piecing together “shame” and “joy” to make “shamejoy,” as in German. Shame and joy are antithetical, distant, never meant to share the same bed.

That’s because schadenfreude does not square with America’s national obsession with the comeback story. Sure, we snicker along with the rest of the world when others stumble, but our culture is built on possibility. Here, the harder you fall, the greater the potential to get the hell back up—at least in theory.

Americans love it when the down-and-out overcome their misfortunes rather than succumb to them. Our founding fathers became the original underdogs when they stood up to their lordships in Britain, although the Native American population would be hard-pressed to agree (that’s where the “in theory” part comes into play). Horatio Alger novels published from the 1860s onward popularized the idea of the rags-to-riches narrative, and the myth of bootstrapping endures in today’s political rhetoric. Speaking of politicians, let us not forget those who get caught with their pants down and manage to stay in office (Bill Clinton) or go on to ambitious second acts (Bill Clinton). On the other hand, it’s been damn near impossible for Monica Lewinsky to achieve any sort of redemption. The puritanical gender politics that shielded Clinton from the brunt of America’s collective schadenfreude subjected Lewinsky to it. Even some of the loudest feminist voices joined the chorus. But if the headline of her recent essay in Vanity Fair speaks to a larger truth, it’s that “shame” and “survival” go together. Shame and survival is the American way. There is no other option.

Schadenfreude does not square with America’s national obsession with the comeback story.

What is it about American history that distinguishes our reaction to schadenfreude? The exceptionalism that so many of us believe is our birthright. Every student wants an A, but not if that means the entire class gets one, Portmann says. Such demands, in the classroom and beyond, are rare in Germany and other countries across the Atlantic. “Europeans are very well aware that—you pick the country—theirs is not the largest economy in the world, none of them is a superpower, so they’re much more tempered in their desires and their expectations than Americans are.” In some ways, this attitude works to our advantage; ostensibly, there is no shame too great for us to overcome. But it also contributes to a cycle of shame and redemption that often plays out via Twitter feeds and text messages.

Consider Hollywood’s take on schadenfreude: Lather. Rinse. Repeat. For every reality show that revels in the exploits of Real Housewives, there are countless celebrities who are capable of Oscar-worthy deliverance. Robert Downey Jr. comes to mind. Lindsay Lohan, if she just listens to Oprah this time around. By this time next week, Beyoncé’s family feud will be old news. Is this healthy? Not exactly. But neither is the alternative. Neither is letting shame define you.

And so Americans may joke at the expense of the fallen, but we keep electing them to public office. We keep paying to see their movies and download their music. It’s the intensely American desire, or arrogance, that celebrates a success story, even if it’s someone else’s.

Pitted against this national narrative, my penchant for schadenfreude appears even more incongruous. I need an attitude adjustment. Or a one-way ticket out of the country.

If I stay here, I’m in bad company. Perhaps the best-known example of schadenfreude in American pop culture comes from Avenue Q, the enduring Broadway hit that won the 2004 Tony Award for Best Musical. The world of Avenue Q revolves around furry, foul-mouthed puppets and their human friends, inhabitants of an apartment complex managed by a fictionalized version of Gary Coleman as a fallen child star turned building superintendent. It’s sort of like Melrose Place with puppet sex and musical numbers, among them “The Internet Is for Porn,” “Everyone’s a Little Bit Racist,” and “Schadenfreude.”

Bobby Lopez, the show’s co-creator and co-author of its music and lyrics, says the song is meant to encapsulate the Gary Coleman character’s joyful refusal to allow ousted tenant and destitute puppet Nicky to crash on his floor.

“I remember reading that scene and immediately thinking it screamed for a song called ‘Schadenfreude’ in the tradition of ‘Hakuna Matata’ or ‘That’s Amore’—the kind of song which takes a foreign word or phrase and defines it for American ears,” Lopez told me in 2010, shortly after the Yankees’ victory, at a time when he is famous but not so famous that he’s thought to remove his personal email floating around the internet.

“I thought the obscurity of the word, the darkness of human nature it referred to, and its long German-ness, would be funny. I also thought it would fit especially well, considering that Avenue Q is written in the style of an educational show, and that the song is teaching a new word or concept.”

Americans may joke at the expense of the fallen, but we keep electing them to public office. We keep paying to see their movies and download their music.

Indeed, the song is crafted as a tutorial for the uninitiated, or for the holier-than-thou set.

“Schadenfreude? What’s that, some kinda Nazi word?” Nicky asks Gary Coleman.

“Yup! It’s German for ‘happiness at the misfortune of others!’ “

“‘Happiness at the misfortune of others?’ That is German!”

To the contrary, the concept of schadenfreude is no more German than it is American or any other nationality. It’s an automatic human response that the Germans simply have managed to name more efficiently than the rest of us. Even Lopez says he succumbs to an occasional flare-up “when other people’s musicals get bad reviews, which is an awful thing to admit.”

“I try to resist it, because I know what goes around comes around,” he says. “But then someone else will feel good, so I suppose it all evens out.”

That karmic outlook has been kind to Lopez: Since I last corresponded with him, he’s achieved even greater success on Broadway with The Book of Mormon and in theaters with Frozen. It also aligns with the uniquely American attitude toward schadenfreude. Embrace it if you must and then, as Elsa sings in Frozen, let it go.

Portmann, the University of Virginia professor, similarly characterizes schadenfreude as “part of an emotional exchange in human society.”

“We don’t like having to pay, but by paying, we do get something eventually,” he says. Every person experiences misfortunes while trying to forge a better life.

But not every person wants to pay.

Portmann points to “tall poppy syndrome,” a sentiment he says is prevalent in the cultures of New Zealand and Australia. Tall poppy syndrome calls for felling any flower that dares to crest the uniform, red-petaled fields. For acting on schadenfreude instead of merely feeling it. “People who distinguish themselves get more glory, but they’re also much more vulnerable,” Portmann says. “You hear parents [in those countries] tell their kids, keep your heads down, don’t stand out from the crowd and you won’t get bullied, you won’t get picked on.” No helicopter parent in America would dare tell a child to stand down in the face of adversity.

Rooted in American soil, the tall poppies have far less to fear.

Then there are those times when someone really deserves to be the object of our schadenfreude, or we think that he or she does. As Gary Coleman sings:

Sorry, Nicky, human nature—

Nothing I can do!

It’s...

Schadenfreude!

Making me feel glad that I’m not you.”

What, then, to make of my own experience at the bar the night of the Yankees-Twins showdown?

“Schadenfreude tells us something important about how a person views the world—what constitutes suffering and what counts as an appropriate response to it,” Portmann writes in When Bad Things Happen to Other People.

Would chanting “Suck it, ‘Sota?” when the Twins are at bat be an appropriate response? I guess that means I’m petty. Schadenfreude is a reaction to trivial matters, Portmann says in the book. But it also has what he calls an “emotional corollary”: justice. “The joy of Schadenfreude is not diabolical, because a belief about justice lies beneath and morally justifies that joy,” he writes.

So let’s weigh the crimes of my exes. Although I abandoned my East Coast allegiances for a baseball cap embroidered with an interlocking white “T” and red “C” for the mighty Twin Cities, Lake Wobegon’s native sons scorned my attempts to adopt their fanatical love for their state and their home team. I recall searching Washington grocery stores for an elusive, heart-attack-inducing snack food called cheese curds to bring to a “Minnesota Party” hosted by the second ex when I was still with the first (and no, there was no overlap). The Facebook invitation welcomed anyone and everyone from Minnesota and “some trash from New Jersey…that means you Christine.”

My ignominy indeed culminated with Minnesota, The Sequel. He decided to take an extended, post-graduation wilderness trip and asked that I send him updates about the Twins’ summer season. I wrote weekly letters that detailed each game, every score, and how that affected the team’s standing in the league. I could almost picture him poring over my detailed sports accounts and the issues of the Economist he requested, toasty and dry in his tent thanks to the hand and foot warmers I sent via Priority Mail. Surely, he would make whatever-we-were official when he returned. I had Twins-Orioles tickets waiting for his upcoming birthday. We went to the game and on a few more dates, but we talked even less than we had when thousands of miles separated us. He waited to end things at just the right moment—shortly after we buried my grandmother, who had all but raised me.

Had I known whatever-we-were meant nothing more to him than what he could get out of it, I might have aimed a fastball at a certain low, vulnerable point on his body. But that would have taken schadenfreude too far: I’d be the cause of pain instead of an enthralled bystander. And it doesn’t take into account my role as a Stage Five Clinger that drove this 23-year-old guy far, far away. I hadn’t yet learned that you can’t make someone love you. I’m grateful for the lesson. It reminds me of a message I still hold dear from Jeff Marx, the other half of the genius behind Avenue Q.

“I tend to feel bad for people’s failures more than I feel glad about them, but it is truly a natural human reaction, especially concerning people you don’t like,” Marx wrote. “There are a few people I wouldn’t be sad to see getting pooped on every once in a while.”

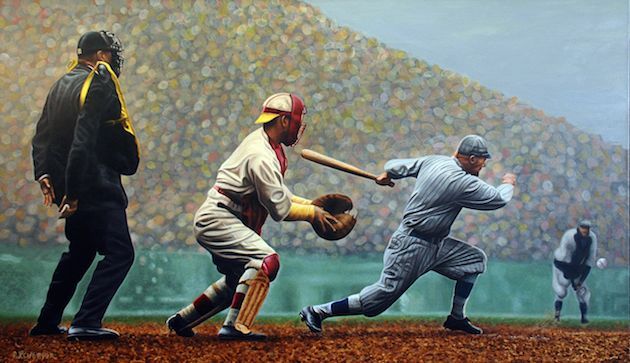

More suitors have come and gone since my Minnesota entanglements, and a wonderful one has even stayed with me for the long haul. I wish I could also say that I’ve evolved beyond my tendency toward schadenfreude. It’s a fun little indulgence, but it should foster inner growth, not inhibit it. Embracing my fellow Americans’ view of schadenfreude should make it all the easier to leave behind. Our predisposition toward redemption is almost as American as baseball.

Then again, sporting events are arenas practically dedicated to schadenfreude. And so I found myself having a Twins-level reaction during Super Bowl XLVI. I don’t even like football, but it didn’t matter. The sadder Tom Brady looked, the louder I cheered. I just kept picturing my most recent ex at the time, a Masshole in my opinion, as the New York Giants squeaked past the New England Patriots. It wasn’t the most constructive thought. At any time, any of these teams could come back and kick some New York ass. And who will be the object of schadenfreude then?