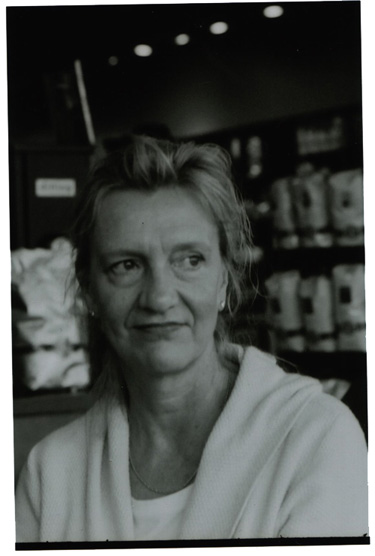

Elizabeth Strout

Our man in Boston sits down with author Elizabeth Strout to talk about Maine, her latest novel, and the plights of the modern writer. Now with audio excerpts.

Elizabeth Strout is of a generation of American writers who, thankfully, persist in writing engaging and engrossing literature in the face of the usual and occasionally unusual, insuperable odds. As our conversation below exhibits, she is fully and happily engaged in the writing life and as her recent work indicates she does the storytelling and writing part well. She was born in Portland, Maine and is proud of her 8th generation Maine roots. That pride, as well as comfort with the ways and world-views of her origins comes to play in her fine recent novel (in stories) Olive Kitteridge. Strout, previously the author of Abide With Me and Amy and Isabelle, has won a number of meaningful literary awards and teaches at Queens University in North Carolina, a low residency writing program (which is described in our chat). She currently lives in New York City and as you will learn from our talk below, is an avid and enthusiastic transplant to the big city.

Olive Kitteridge, a whole cloth woven of various story threads centering on an elderly Maine woman, was positively and widely reviewed. Louisa Thomas in the New York Times offers this praise:

“The pleasure in reading Olive Kitteridge comes from an intense identification with complicated, not always admirable, characters. And there are moments in which slipping into a character’s viewpoint seems to involve the revelation of an emotion more powerful and interesting than simple fellow feeling—a complex, sometimes dark, sometimes life-sustaining dependency on others. There’s nothing mawkish or cheap here. There’s simply the honest recognition that we need to try to understand people, even if we can’t stand them.”

We agree.

RB: So you drove in from town, from Boston?

ES: Yes.

RB: Where do you live?

ES: I live in New York City.

RB: So, when you drive from wherever you were in Boston, what does this look like?

ES: I love it, I just love it, because I grew up in Maine, and I lived in Boston many, many years ago. It’s sort of like the first stop, you know, if you’re leaving Maine and you’re going out into the rest of the world.

RB: I thought people went directly to Montana or something like that. Just kidding.

ES: Or California. I came to Boston. I am so happy to be back on the East Coast—having just come in from L.A.

RB: Because?

ES: Because I love it. I can’t explain it.

RB: It’s not that you don’t like the West Coast…

ES: I guess it’s a sense of familiarity, a sense of region, a sense of home. Like when I was in the airport yesterday in L.A. and I heard this woman with a Boston accent, I was so happy, I was just so happy. Coming from Maine, one understands there’s a difference between a Maine accent and a Boston accent. Nevertheless, at this point in my life, they’re both equally familiar to me and make me just… glad.

RB: Why don’t you live in Maine?

ES: Because I live in New York [laughs]. Which I love.

RB: One could easily say that Maine and New York are not exactly the same.

ES: One could easily say that, and they’d be right.

RB: What is it that you like about New York?

ES: I like how many people are around. I love the energy of New York…but I miss Maine.

RB: Do you think that people think differently in Maine?

ES: I do, I think that people think differently in every region. I think that it’s less and less true because more and more people are moving, but I do think that regions have their own way of thinking.

RB: How hard was it for you to put yourself into the worldview behind the eyes of all these characters that live in a small, or, I don’t know, a large town—Portland? Living in New York City and listening to conversations that I imagine are faster and more brand-name filled…

ES: Um, it was very familiar. I think I lived with a low level of…Although my current work is including New York City for the first time, I think in colloquial spheres. It’s the level of comfort, it’s easy for me, and desirable for me, to go back and to imagine those parts of my life that I can remember.

People bring their own life experiences to every book, and so whatever book I write will be a different book for every person who reads it. It’s their book: I give it to them.

RB: So how hard is it—do you visit Maine often? Do you get refresher courses?

ES: I do [laughs]. I don’t feel they’re refresher courses, because I feel like it’s always inside me, but I do visit Maine, more frequently, over and over again.

RB: I just stumbled across asking you about the difference between how people think in New York and Maine, but I really want you to tell me about imagining and creating all these dialogues and relationships with all these fictional people in which not a lot is happening, not the drama that we’d expect in most entertainments, but things are happening in people’s lives—serious things. So, how do you think about all these people?

ES: I guess I’m really interested in individual lives, I’m interested in the quiet—because they’re not quiet, because our internal life is never quiet, or maybe for some people it is, but I think that for most of us our internal life, we are wrestling with all sorts of…and then there’s this outer world: What’s our relationship with that? But the interior things that are going on in, while we’re trying to cope with our spouse, our changing spouse, our changing circumstances, the aging process, our relationship to young people changes—all this kind of stuff was very interesting to me, regarding Olive.

RB: For the most part the characters are in their golden years. There are a few characters—the son, Rebecca—

ES: Nyena…

RB: But mostly it’s about people who don’t have what we would call big lives, but things happen—and they’re not things that I think have happened to you.

ES: No, they’re not things that have happened to me, and yet there is some sense that everything that I write about…I had to have experienced some aspect of that emotion in order to write about it, and then I push it to the utmost extreme. But, no, you’re right: When Olive is taken hostage in the hospital bathroom with her husband and the doctors and nurses, it’s not something that’s happened to me, it’s not something I’ve ever heard about happening to anybody, and yet it was something that came to me and I was really drawn to the idea that under this pressurized situation, what would come out of your mouth? And poor Olive, she is this engine that can’t stop herself, and there she is, blurting out these dreadful things.

RB: Do you have a stake in what people think of her? As an author, do you want people to like Olive?

ES: That’s an interesting question. I feel very strongly that people bring their own life experiences to every book, and so whatever book I write will be a different book for every person who reads it. It’s their book: I give it to them. And so in a certain way, no, I don’t have a stake in whether people like Olive. Some people have told me they absolutely love her, and some people have said they can’t stand her but they’re still very drawn to the book. And so I don’t have a stake in their reaction to Olive, I have a stake in their reaction to the book. I hope that even if they have a negative response to much of Olive’s behavior, they are maybe still drawn into this humanity that is underneath all of her action[s].

I’m so interested in the fact that we really don’t know anybody. We think we know the people close to us, but we don’t, we really don’t.

RB: In many novels, you don’t have to deal with a number of narrators, and make decisions about their liability and all that. Do you feel like it possibly places a larger responsibility, if not burden, on the reader because they have to decide…?

ES: Well, I think that to use different narrators actually helps the reader—that’s how I would see it. I deliberately did that because I think that Olive is such a complicated character that in order to see it from different points of view—the way I chose to construct the book—I did that to give people a break from the full-front effect of her, and also because it helps me, and I think it helps the reader, understand that we’re all more complicated that we appear. There are different aspects of Olive, and these different ways to look at her, I think, help to bring that out.

RB: Did you accept the testimony? For instance—again, I’m not sure what I thought about her son’s reaction to her and whether or not he was being fair. So, having said that, I could say, well, maybe none of these people knew her, or had the humanity and the intelligence to grasp her individuality.

ES: Exactly, I think that’s true. And—I’m hoping not to sound trite—I would say, how well does any one of us know anybody, really? And that’s an interesting thing for me, and that’s one of the reasons that I write—because I’m so interested in the fact that we really don’t know anybody. We think we know the people close to us, but we don’t, we really don’t.

RB: That reminds me of a line from a Van Morrison song called “The Meaning of Loneliness.” It has a line: it takes more than a lifetime just to get to know yourself.

ES: Exactly, and that’s if you’re lucky.

RB: Yeah [laughs].

ES: So the idea that Olive’s son is perhaps being unfair to her is, I think, really legitimate. At the same time, there are different things that we have where we see that she may have a conductively superior oath for him that is quite extreme and perhaps is not as black-and-white. So those ambiguities are what interest me.

RB: Now on the other hand, you have her sweet-natured husband, who can perfectly well tolerate her and understand her moods and her reactions and things like that.

ES: I don’t know if he can perfectly well tolerate her, but he certainly does a good job of trying. I think that in the story you referred to earlier, when they were in the bathroom in that hotel under that pressure, there was some sense of the anger he may have had over her relationship with her son—and her relationship with his mother also comes up—but no, you’re absolutely right, he is a very decent, steadfast—

RB: Even in his relationship to other people in the community—he does sort of represent the iconic ideal of the “community person.”

ES: Exactly—the fact that he’s the pharmacist is relevant. He is the one who’s helping to alleviate suffering—literally and metaphorically.

RB: Where did you start with this story?

ES: I think the first Olive story I wrote was the one about her son’s marriage—his first marriage—called “Little Birth.” I believe that’s the first story I wrote, a number of years ago. But I knew at that time that this was a character I was going to write a book about—that she would have a full book. And I also knew at that time that it would probably be in the form of stories that could stand independently—although I think of this book as a novel, really, because it has the heft of a novel, it has the arc of a novel: This woman’s life is being addressed. But I think that I understood early on that it was going to be called an “episodic narrative” because that’s how we could separate her in these different points in her life.

RB: So you wrote a story, you knew you wanted to write more about Olive, and then you wrote a few more stories? Or you then, at some point, decided you were going to have to go for the whole?

ES: I did. I wrote a few more stories, and some came to me more easily than others, which is the way it is. The hostage bathroom story took me a longer time, I had to do some reading—I was very interested in the Stockholm syndrome—and sort of had to find the form of that. You always have to find the form of any story, or any book. So that one took me a long time.

RB: You could have disposed of Henry in any number of ways. You chose a particularly sort of painful one.

ES: Yeah, it is painful. I thought about that. I think that there was at some point a decision whether or not I was going to have him just die and just not be there, and then I thought, no, I don’t want to shy away from the realities of life. Nor do I want to gratuitously rub a reader’s nose in sad stuff, but the fact of the matter is this is something that happens to many people. So for her to deal with that, to see him, and to talk on the phone with him, and to try and continue that relationship—I think we speak to that, I think that’s what some of us do.

RB: Now that you mention it, it’s conceivable to have him die, and she might have continued to talk to him in some way.

ES: Right, because people do. People respond to death in many different ways.

RB: The professor—she meets him when falling down…

ES: Right.

RB: He’s the one that who announces that his wife has died. But she has never, in any of the interior dialogue, actually ever said that.

ES: She has not admitted that to herself. This is just the way that I see her. She has these particularly ferocious passions, and they scare even her. And so when she’s at the post office and she gets rid of the mail right there because she can’t bear that it has his name on it…. She writes back to condolences, “don’t feel sorry, this is what happens.” She’s very defiant, or trying to be defiant against the intensity of her pain, which is almost unbearable.

RB: And is she seeing [Henry] just for the company? Is there anything about him that she likes? Would you know?

ES: I think it’s his honesty. In a certain way, she’s honest. She may be blind to what her actions do to people and yet she’s quite perceptive and quite honest, and I think my understanding of her would be that she’s drawn to his honesty, and he says, “I have rejected my daughter and she hates me and it kills me,” and so they have a chance together to share these things that they’ve done to themselves and to others. So there’s some mutuality there that she ultimately understands she can either reject, because she is such a rejected person, or she can give herself a chance.

RB: So, how long have you lived with her?

ES: Well. I guess probably about 10 years.

RB: And could you foresee ever writing about Olive again?

ES: You know, I never know. I did come across this story that I had started, another Olive story—after Henry died, and I was so sorry—when I thought, oh, hey, there she is again. And I’m a very messy, unorganized person—

RB: And you immediately brought her up on your hard drive?

ES: No, no, I write by hand and leave things scattered all over the place.

RB: That’s terrible.

ES: It is terrible.

RB: Especially when someone calls and asks you for something. I have a lot of photographs that people are always calling and asking for and I’m always trying to find them.

ES: [Laughs]

RB: Have you attempted at all to revisit Olive in her youth?

ES: No, not right now I’m not.

RB: So if you revisited her, if you ascertained the idea of writing about her again, would it be at this point in her life or beyond this story?

ES: It’s just impossible for me to know. I just don’t know, because I’m not at the moment compelled to write about it.

RB: So inhabiting a character’s life for an extended period, it’s not a haunting experience?

ES: Well it is a haunting experience. It’s a strange experience. And I’ve though about this with each of my books, because they, in a huge way, do occupy me [within] my mind, and when I’m not writing about them I’m mulling over who they are and what they might do. And I live with them and love them for long periods of time and then they’re done, and I sort of can’t imagine they ever will be done, but then they are. And so far, luckily, there’s been another emergence of something else.

RB: So that’s what happens: You come up with something else.

ES: Yeah, I’m not as bereft as I should be. I sort of feel guilty about moving onto new stuff, like, look at how fickle I am.

RB: But what is it that has drawn you away from the story that you’ve put out and published?

ES: It’s not that I’ve been drawn away from it, as much as what I’m working on now is the more compelling thing for me.

RB: How does that enter your consciousness?

ES: The new one?

RB: Yeah, do you have a box of notes somewhere?

ES: No. I mean, that is truly—that is really a mystery to me. I never understand why I write the stories that I write or the books that I write. I don’t really know.

RB: But you know that you write them because they give you some—what is the feeling?

ES: Oh, the feeling is wonderful; the feeling is one of great pressure, usually in a very good way, you know, like, oh, right, here’s a person or here’s a story or here’s a situation…and that’s a lucky thing.

RB: You said something about how maybe you’re not as bereft as you should be—has there ever been a project that you completed and you didn’t have something else—

ES: No, but that’s the fear.

RB: [Laughs]. It never happens but you are afraid of it.

ES: It hasn’t happened yet, but I am afraid of it. When one lives by one’s imagination, you can always imagine the worst.

RB: You know I used to talk to a lot of writers and I used to try to learn as much as I could. Now I don’t anymore. So, you teach at a college in North Carolina? Where is that?

ES: It’s a low-residency program in Charlotte, N.C..

RB: There’s a burgeoning of low-residency programs, now?

ES: Yes, absolutely, they’re popping up all over the place.

RB: Because people can’t devote their lives any longer…

ES: Yeah, they make a lot of money for a college…well, more and more it’s just very good, original, very high-spirited, and there are many of them now, all over the place, and I think they speak to the needs of many people who want to get an MFA and can’t do it on a full-time basis.

RB: I only know of two others.

I wanted to be a writer so much that the idea of failing at it was almost unbearable to me. I really didn’t tell people as I grew older that I wanted to be a writer—you know, because they look at you with such looks of pity. I just couldn’t stand that.

ES: Oh, well, there’s a lot. [Laughs] I mean, I can’t list them, but there are a lot of them.

RB: I mean, it makes sense. It didn’t make sense to me that 25,000 or 30,000 people a year are in writing programs. That I don’t understand.

ES: Well.

RB: So, I guess I understand the industry. So, you teach, you write, you skydive.

ES: No, I totally do not skydive, although one time I did go up in one of those parasails to see what it’d be like to be a bird, and I was so frightened.

RB: How high were you?

ES: About 300 feet, I think.

RB: Over water?

ES: Yeah. In this little canvas seat—like a swing set on a playground, basically.

RB: Did you have a guide with you or did you do it solo?

ES: I did it solo.

RB: Good for you.

ES: Oh, it was terrifying. I was so terrified, it was horrible.

RB: So, what’s the interplay between teaching and writing? I assume you’re teaching writing.

ES: Yes, I’m teaching writing. The interplay is—it’s positive and negative. The negative part is that it uses similar energy, and a writer is always so protective of that energy because it’s what we live off of, so it’s a little hard sometimes.

RB: But you teach two times a year?

ES: Exactly, two times a year. But they send their manuscripts once a month. I know people who say that teaching helps their work. I’m not one of them. I don’t think that teaching helps my work. If I thought that it harmed my work then I would look elsewhere for employment, but I enjoy most of my students and I enjoy watching them learn to read better because reading is such an important part of writing.

RB: How many people go to Queens University? Are there many people from North Carolina?

ES: Not really, they come from all over the country.

RB: Because it always struck me that North Carolina has more writers per square inch than maybe Des Moines or Brooklyn.

ES: Well, Brooklyn, no, everybody comes from Brooklyn now. The South has such a great heritage, [but] they’re so embarrassed to call themselves writers.

RB: I missed the phrase-reversal: It used to be sort of an insult to call someone a Southern writer. But people don’t say “Southern” anymore.

ES: I guess, I don’t know. I think being a Southern writer is a wonderful thing, I think their heritage is so rich and so wonderful. Yeah, I think it’d be great to be a Southern writer, but I’m a New England writer.

RB: I asked a writer named Joan Frank what she was reading and she mentioned Thornton Wilder, and I was trying to think of other New England writers other than Stephen King, Robert Frost—

ES: Robert Frost.

RB: Is Richard Russo a New England writer?

ES: Well, he’s an upstate New Yorker. He lives in Maine, but he’s from upstate New York.

RB: Richard Ford?

ES: Richard Ford is definitely a Southern writer, but he lives in Maine.

RB: Is there a Maine epic, is there a Maine point of view?

ES: I think it’s so hardcore individualistic, so… you know, I come from eight generations of Maine on one side, and my family has 10 generations of Maine on the other side.

RB: From what I understand, Maine was a pretty progressive and advanced place throughout most of the development of the country, and they’re done with that.

ES: Well, Maine is formed. It has a high poverty level, it has a very depressed economy—and has for years, particularly when you get off the coast.

RB: Even on the coast.

ES: Even on the coast. It depends on many out-of-staters, and there are more and more out-of-staters.

RB: So you knew at what point that you wanted to be a writer?

ES: At a very early point. My mother bought me notebooks when I was very young, four or five years old, and she would say to me, “Record what you saw today.” If we’d gone to buy sneakers, she’d say, “Write what the salesman seemed like.” And so from a very young age, I just thought in terms of sentences.

RB: Was that fun for you at that age?

ES: Very fun. Fascinating.

RB: At what point did you sort of grasp what it entailed to be a writer in this world?

ES: Well, rather early on. I wanted to be a writer so much that the idea of failing at it was almost unbearable to me, and so I really didn’t tell people as I grew older that I wanted to be a writer—you know, because they look at you with such looks of pity, and ask what you’ve published—whatever, I just couldn’t stand that. And so I didn’t really tell people.

RB: Do you think there are some small, finite, predictable conversations when one says they’re a writer?

ES: I think so, yes.

RB: [Laughs].

ES: There’s the first response, “Well, I’ve always wished that I had the time to be a writer,” and that’s sort of like, OK… and then the second response is, “What have you published?” and the third response, which has always sort of appalled me, is that people will say, “Well, you know that very few people are ever successful at that.” And so it carries a lot of negativity.

RB: It’s weird. And yet, at least in the last 10 years, something about writers has begun to clash differently in the mainstream pop culture—you know, you see writers’ names being mentioned in gossip columns.

ES: That’s right. We’ve hung in there.

RB: Have you ever been mentioned in a gossip column?

ES: I don’t know, I don’t read [those] things [laughs].

RB: But people would call you and say, “Look at her!” [Big laugh].

ES: Nobody’s ever called me and told me, no.

RB: So do you feel like you live the life of the writer? Do you go to conferences? Do you go to Yaddo?

ES: I’ve been to Yaddo a couple of times. It’s a wonderful place. But I pretty much keep to myself as a writer. I mean, I certainly have friends that are writers, but I don’t actively partake in a so-called literary life.

I think that one can write as well as one reads.

RB: Even in New York?

ES: Even in New York.

RB: No publication parties, or readings?

ES: Oh, yeah, there are publication parties and readings, but that’s not the center of my life, those are just pieces of my professional life.

RB: Would you feel disconnected? Do you care when you’re connected to the world of publishing?

ES: No, I don’t care. I just want to be published and I want to be read. I know that there are writers who put a great deal of time into fostering their careers as well as their work, and I respect that and I admire it, but it’s not in my nature, I can’t do it. I put most, if not all, of my energy into the work itself and then hope for the best.

RB: So, what does it mean if you’re going to spend three or four weeks on the road?

ES: Yeah, it’s hard. I mean I’m glad that my publisher believes in my work and wants me out there, and it’s nice to meet readers, it really is, because writing is such a solitary endeavor, but it certainly is not—I’m not a person who travels easily or well.

RB: So, do you do much besides reading and writing? We’ve eliminated skydiving.

ES: We’ve eliminated skydiving, and that can probably stay eliminated. I love the theater, and I love going to all sorts of off-Broadway or off-off-Broadway productions in New York, I love that. I love paintings, artwork. I don’t know much about them, but I love to go to the museums and galleries, I really do.

RB: I’m reading a really interesting book by a writer I discovered in the last few years—his name is Michael Gruber—and he just wrote a book called The Forgery of Venus, which has a character that in some odd ways is beginning to think he’s in some experiment. [He] starts to hallucinate that he’s involved in a painting forgery scheme. The reason I mention it is because one thing Gruber does really well is he really incites action that lets you get the idea of how passionate someone can be about painting, about the materials—the light and with the chalk—

ES: Exactly. It’s fascinating. That’s always interested me. And, like I said, I’m not schooled in it, but I’m interested in what I respond to, and the way I respond to it, and the kind of stuff like that.

RB: Do you read a lot?

ES: I read a lot, yes.

RB: It’s not a problem for you.

ES: No, I think that it’s the other half of my job. I mean, it’s directly related to writing, I think that one can write as well as one reads. I have to be careful that there are good sentences that are going into my head because I’m very—hopefully you can tell by the work—I’m very interested in how sentences sound. To me, that’s part of the experience of reading, how the sentences fall on the ear, and so I have to be careful when I’m reading that I read things—you know it’s like eating good food and making sure that the right stuff enters [laughs].

RB: Have you discovered something recently that no one else has read—have you found some undiscovered gem that you want to tell the world about?

ES: You know, he’s certainly not undiscovered but I always want to tell the world about Oscar Hijuelos. I love his work so much.

RB: Oh, yeah. All of it.

ES: Like I said, he’s not undiscovered but…

RB: I think people went crazy over the second or third one.

ES: Well, he won the Pulitzer Prize for [The] Mambo Kings [Play Songs of Love].

RB: But then the stuff after that—

ES: —is absolutely fabulous.

RB: The cleaning lady… [Empress of the Splendid Season]…

ES: Oh! That wonderful, wonderful book…

RB: And then A Simple Habana Melody.

ES: Yeah, I just love his stuff. Love it, love it, love it.

The world is changing, whether we like it or not. I do actually think that we need stories in order to understand ourselves.

RB: I’ve talked to Oscar a couple of times. I have a wonderful picture of him that I took—he spoke at the Brattle once—and I just got him backstage and it was really low light and I don’t know how I even read the thing but I just got all the right shadows. I love that picture. He has one of those typically Cuban, melancholy personalities, like he almost wants to complain about everything? [Laughs]

ES: Yeah, I just love his work so much. I’ve met him, I think, twice or three times. And every time I’ve met him, I’ve said, “Hi, you don’t remember me but I’m the one who just absolutely adores you”—I mean he’s got other people who adore him obviously as well—but he always [says], “Oh, thank you,” sort of surprised. But I just think he’s very, very special.

RB: Well he’s not one who, from what I could tell, at a personal level, seems to encourage people to [interact with him]. What was the last thing he wrote, Habana Melody?

ES: I believe that is the last thing he wrote, yeah.

RB: That was about a Jewish violinist.

ES: Yup.

RB: Right. I should go back to that. So in all of this dedication to writing and literature, do you think what you do is important?

ES: You know, it’s such a good question, because recently, you know, with the state of the world—I’ve always wanted to stay away from complaining about the state of the world because I think that it has always been precarious, but I have to confess that recently I really do think the state of the world is precarious—

RB: Precarious-er.

ES: Exactly. And I do think to myself, “What’s the point of writing,”—particularly, “Why am I writing about this older white woman from New England? What’s the point in that?” And yet my answer is: It’s always, always important to have stories. And I’m recording a time and place in history and about a particular woman from a particular heritage, and this country is changing, and in ways it’s very good.

RB: It is? In many ways?

ES: Well, I think that we don’t need to remain as territorial as we’ve been in our different regions. I would like to think that some of the changes are good, [with] people moving around more and having more tolerance—

RB: Can you imagine driving with Massachusetts license plates up to Maine that often?

ES: But I think that that is changing. And I think that in another generation or two you won’t necessarily have a reaction.

RB: Because the people who live in Maine won’t be able to afford—

ES: They won’t be able to afford living there—

RB: And the people who live in Martha’s Vineyard won’t—

ES: Exactly. So the world is changing, whether we like it or not, so I think its important to record all of [Olive] Kitteridge’s life. I do actually think that we need stories [in order] to understand ourselves.

RB: Could you do it even if you didn’t think it was important?

ES: I would have to. I love writing.

RB: You know there’s no obligation for people to do things—

ES: Someone recently was reminding me of that. No, I do it because I love it. I love it.

RB: Do you have a timetable for when you might complete whatever you’re working on now?

ES: I’m hoping to complete it by the end of this year. I tend to be a little optimistic about these things, but I don’t see any reason not to get it done sooner rather than later. I’m working pretty hard.

RB: And what is the feeling like [when] you’ve finished something? Some writers can’t finish. They write 600 pages and then they just want to keep going.

ES: Well, I don’t really have that problem. It changes a lot during the course of working on something, but I have a sense of putting together a piece of work, and when it’s done, moving on to the next one.