On election night, when Florida’s results mysteriously stalled and Clinton supporters such as myself grew nervous, I drank some gin. My 12-year-old son went to bed. My wife went to bed two hours later. By midnight, Trump’s victory looked all but certain, and I wrote my son a note. If I’d known that a million-plus people would read it within the coming week, I probably would have worded things more clearly and attempted better penmanship.

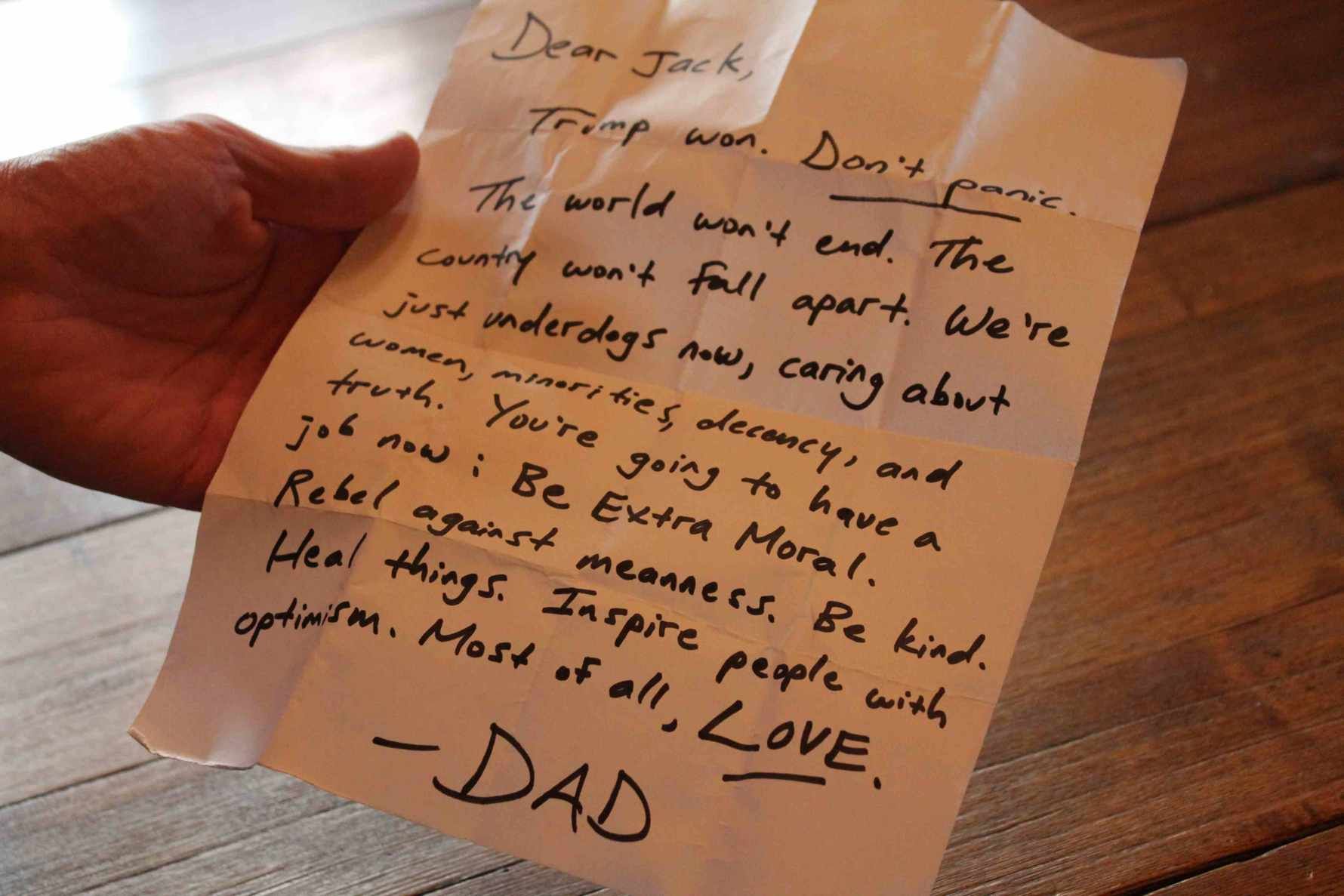

Dear Jack,

Trump won. Don’t panic.

The world won’t end. The country won’t fall apart. We’re just underdogs now, caring about women, minorities, decency, and truth.

You’re going to have a job now: Be Extra Moral. Rebel against meanness. Be kind. Heal things. Inspire people with optimism.

Most of all, LOVE.

– Dad

Cornball, yes, but totally sincere.

My wife and I, along with many of our friends and relatives, had spent the year discussing a Trump presidency as the worst-case scenario for our country, and perhaps even the world. We were revolted by Mr. Trump’s hateful and untruthful rhetoric and behavior. We feared his environmental policies. We were alarmed by the thought of Mr. Trump gaining control of the nuclear codes.

I worried my son would wake to the news of Trump’s win and be scared shitless. I was scared shitless. What exactly would a Trump presidency look like, what were we supposed to do about it, and how could I explain it to my son?

I wrote the note with a Sharpie on a piece of printer paper. It was the least thought-out message I’d written in weeks (I’m someone who often proofreads texts) and was primarily meant to soften the initial blow of Clinton’s defeat.

I left it on the dining room table and went to bed. I’m a later sleeper, so my wife was the parent who watched Jack discover the note the next morning. He read “Trump won,” said, “Fuck,” and walked away. My wife sympathetically pardoned the F-bomb and encouraged him to finish reading. And the note actually worked: he calmed down, felt reassured, and discussed the election with my wife over a plate of Eggos.

Right there, the note was a homerun. I later learned Jack folded the paper and carried it to school in his pocket.

It was travelling out to the world another way, too. I had posted a photo of the note on Facebook because many of our friends and relatives, some of whom are parents themselves, had also voted for Clinton. I hoped the simple words would strike a positive chord on a hard morning. By 9 A.M., a hundred people had liked or commented on the post, saying they’d found the message encouraging and planned to share it with others. A few parents read it to their own children. I smiled a little and went back to traumatizing myself with news articles.

Midmorning, a friend texted to say my note had appeared on Instagram, posted by a non-mutual third party. Others were emailing, texting, and quoting the note to relatives and coworkers. I rechecked my original Facebook post throughout the day. A thousand shares. Two thousand. Four thousand.

Strangers sent me appreciative messages, saying the note had touched them and others they knew. A preacher let me know she’d included the note in her sermon at a nursing home, where it was well-received. I didn’t know how to answer anyone who contacted me. Thanks? You’re welcome? I kept responding politely and thought it was all very weird.

Things got weirder. The photo of the note didn’t have any stamp of authorship aside from “Dad.” Getting credit hadn’t been the point. People misattributed the source, copied and pasted the message, paraphrased portions, and claimed authorship. One woman designed and started selling a “Rebel Against Meanness” T-shirt, all proceeds of which would go to the ACLU.

Half a dozen people told me things like, “I was having dinner over the weekend and my mother-in-law said, ‘I saw this wonderful little note on the Face Book today …’”

An odd mix of celebrities shared the note: Scout Willis (Bruce and Demi’s daughter), the co-creator of TV’s Arrow, Miss Nicaragua 2013. Someone reposted the note on Pantsuit Nation, a private Facebook group with 3.5 million members, where it got thirty-five thousand likes and was shared even further. The Daily Buzz published an article about the note, misattributing it to a father writing to his gay son. That article was shared by George Takei on his Facebook page of 9.9 million followers.

The Daily Buzz article was later corrected, but Mr. Takei’s original post and headline remained. In other words, my son Jack was incorrectly outed by Mr. Sulu.

Jack agreed this was kind of fantastic.

But not everyone liked it. The Pantsuit Nation group is private, I assume, in part to provide a troll-free space for Clinton supporters to interact. Based on the reactions I saw, the note was overwhelmingly enjoyed by the Pantsuit members, but some people took umbrage. A woman I don’t know sent me the following message:

Dear Jack,

You will grow up to be a white person with a penis. The world is your oyster!

Love,

Dad

I decided to answer. My response began with an apology for striking a poor chord. I explained my motive for writing the note and clarified that, yes, although Jack and I were white males, we had many loved ones—including Jack’s mother—who felt directly threatened by Trump’s election. I told her the note was only a moment in a much deeper, lifelong conversation with my son.

She replied with a long, heartfelt message and shared her personal experiences with regard to the election. I better understood why the original note had angered her, and the next day, I clarified some of the points with my son.

“We’re just underdogs” didn’t mean “us white guys.” It referred to everyone who voted for the losing candidate—everyone standing against Trump’s hateful words and behavior. I reminded Jack that he and I—straight white guys—are the least threatened and disadvantaged people under a Trump presidency. It would be easy for us to remain bystanders and hope for the best, but we’d be failing everyone who isn’t us, including a lot of Jack’s classmates, friends, and relatives. “Easy” in this case would be evil.

My conversation with the woman from Pantsuit Nation ended on a positive note.

Negative comments on George Takei’s page, however, did not inspire direct engagement. That’s a public page, open to trolls, and although many of Mr. Takei’s followers liked my note, many others attacked it. But some of the kickback came from non-trolling people who said, in essence, “Just because we voted for Trump doesn’t mean we hate women, minorities, LGBTQ, etc.”

I had dinner with a friend whose father, a white man, spent his life working 60 hours a week and barely scraping by. The father is 65 now and has nothing saved for retirement. He hears people talking about white male privilege and says, “What privilege? I’ve been struggling all my life.” He voted for Trump because he believed Trump would overturn the system that failed him, and millions like him, for decades.

Jack has classmates whose parents voted for Trump. We’ve known and liked these families for years. Do I tell my son to suddenly judge them all as intolerant hatemongers? No. But they all voted for an intolerant hatemonger, and we need to understand why.

On the flipside, some people who read the note didn’t want to cut Trump supporters any slack whatsoever. They thought my note was too Pollyanna with its easy talk of optimism and love. Hate crimes and threats are on the rise. Do I really expect my son to “go high” with someone who’s spraypainting swastikas on a public wall? Should he try to love a white nationalist like Steve Bannon?

The love I’m trying to teach Jack isn’t all snuggles and flowers in gun barrels. Love doesn’t always mean “agree to disagree.” It can also mean “disagree.” I tell him to look at MLK. Look at Jesus. This is not snuggly stuff. It’s fiery, hard-fought, blood-and-tears love.

But yes, I also mean love in the nourishing, gentler sense. Many people we know, and millions we don’t know, feel scared and betrayed. Ordinary love can be an extraordinary countermeasure.

Which isn’t to say Jack should consider himself some miraculous world-healing love wizard. A gay man I know reminded me that just because everyone threatened by Trump needs our support doesn’t mean they’re weak. That’s an important ego check for a well-meaning 12-year-old boy (or 42-year-old man). This isn't about saving helpless victims from the train track. It’s about not driving trains over people.

On the subject of checking egos, what special right or expertise allows me to teach a young person anything about the world anyway? None! I had sex with my wife one time and poof, I was a Dad. Perfect readiness and wisdom weren’t—and still aren’t—part of the deal. That first year of fatherhood was the scariest of my life. “Wait-wait-wait,” I thought. “I’m the role model now?”

I had a similar epiphany in Home Depot a few years after I became a father. My wife and I were new homeowners, and I’d developed a DIY enthusiasm for minor to moderate projects. After some brief YouTube research on plumbing repair, I went to the store looking for parts and knowledge. Turned out I knew more than every employee at the store that day. The jarring revelation was that experts do exist, but most adults are winging it, and we’re not nearly as smart or able as we’d like the younger generation to believe.

We try, we screw up, and we occasionally get things right. We help our kids by sharing knowledge and experience, and by encouraging them to try on their own. If all goes well, they do better than we did.

When I wrote to my son on election night, I wanted to encourage him. I wanted to show him I loved him and to reassure him that whatever we needed to do next, we’d do it together. What more can I say about a gin-infused Sharpie note? It sparked conversation. It worked that way for me and Jack. It worked that way for me and strangers. It worked in public forums, private messages, and apparently quite a few dining rooms. It would have worked fine if it had stayed on our own table, but I’m glad Jack took it to school. I’m glad it was passed around.