The exact location of the Lost Horizon Night Market is said to be indicated by a series of clues, but my friends and I simply follow the only people we see out and about at midnight in this remote warehouse district in Bushwick. There is nowhere else they can be going, particularly dressed as they are in gold lamé Spandex, giant white and pink wigs, purple platform boots, lorgnettes, and canes.

We round the corner and see a long line of U-Hauls and box trucks parked down the deserted street, under warehouse roofs, abandoned cranes, water towers, and the silent night sky. At first glance, it doesn’t look like much (“Is this it?” we ask each other. “Isn’t it indoors somewhere?”), but then we spot clumps of costumed youngsters zipping from truck to truck like trick-or-treaters.

We walk up the street, getting the lay of things. Curtains, flapping in the unseasonably chilly May wind, conceal the trucks’ interiors, their crowds, lights, chatter, laughter. We duck into a truck at random. A harried young woman sits at a desk, in front of a coffee table surrounded by chairs. She has pastel-colored currency stuck to her forehead and a profusion of clipboards and forms strewn before her.

“Step into our waiting room, please,” crows a hawker. “We provide a variety of loans for trusted investors such as yourselves. We provide loans and services for business ventures, and seed money. All you need to do is fill out this extensive survey of your personal information. Please, step up, step up.”

“Ms. Uburchu,” calls a man seated behind a half curtain in the shadowy back of the truck. “Where is this man’s extremely personal research survey?”

“One minute,” screams the woman, madly stapling a stack of Post-It notes together. “I am making a facsimile!”

We decide to walk to the end of the line of trucks, and then work our way back, visiting as many as possible. There are 30 in all, too many to take in. The street we are on turns into another, where we run into a fellow we know, a sort of self-styled party guru who is everywhere at all times, and who’d clued us in to tonight’s event. This is the third Night Market (the first was last October), and it’s advertised mainly by word of mouth (well, and Twitter), creating a conscious mystique that would be obnoxious if the event was not so truly cool.

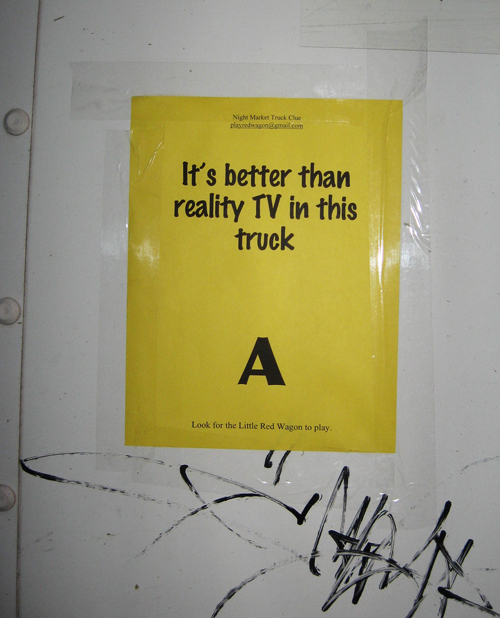

“Are you wearing earrings?” the guy says to me, and holds up his camera phone to photograph my ear. “Woman without earrings. Cross that one off,” he says to a friend. “It’s a scavenger hunt,” he explains. “If you want to sign up, find the red wagon.”

“Next, we need a female clown detective,” says his friend, consulting her list.

“That’ll be tougher,” he says. He earnestly introduces himself to me for the sixth time this year, then spots a man with dreadlocks (another item in the hunt) and runs off.

We continue on our way. Another street lined with trucks terminates at a rusted iron pedestrian bridge crossing a railroad track. We climb up. At the top, people smoke furtively against the open sky, and a girl with a guitar sings “American Pie” to a small crowd of admirers. On the other side of the bridge, more trucks and, finally, the end of the line.

We run from truck to truck, waiting for an opening in the crowd, then push through the curtains and peer past the crowds to see each installation. There’s an old-timey Western bar, wenches and cowboys drinking and brawling. There’s a cozy, mood-lit jazz den, where a pretty young woman croons, accompanied by a guy on drums and surrounded by drained cans of PBR. There’s a small, crowded restaurant with a wraparound table covered in bottles of Sriracha and surrounded by stools. The proprietor in a paper apron enthusiastically dishes out bowls of ramen to a loud, quickly rotating throng of customers. There’s the Jesus Christ Hookah Bar, which is two dudes dressed like Jesus smoking from a variety of elaborate hookahs.

The Night Market is free and/or runs on a barter system. The main currency seems to be cupcakes—half-empty plastic trays of the things are on nearly every surface. There’s also a Sleazy Motel, with two rooms for rent. “There’s, like, all kinds of shit going down in there, man,” someone warns as we walk past the rocking truck.

We sign up for a room. After a two-minute wait (free pregnancy tests to pass the time), we are admitted. The room is pretty small for my four friends and me, but there’s an accommodating filthy mattress, and we jump up and down and rock the van, giving vent to a cacophony of barnyard sounds. Quite the crowd has gathered when we emerge, so there are plenty of people to see me miss an imaginary step coming out of the back of the U-Haul and crumple into the gutter like a puppet with its strings cut. The overhead street lamps keep cutting out, making the trucks somewhat difficult to navigate in the moonless dark.

The Night Market is free and/or runs on a barter system. The main currency seems to be cupcakes—half-empty plastic trays of the things are on nearly every surface. People are friendly and happy to be here; absorbed together in the spectacle, there is no need for small talk. Gypsy cabs circle hungrily, having unexpectedly hit pay dirt here in the middle of nowhere. The cops also hug the periphery, issuing $25 open-container tickets, which everyone agrees is sort of shitty and unnecessary, but whatevs.

We avoid some of the trucks altogether: one silk-screening T-shirts, another pelting everyone with paintballs (“But you get to shoot back!”), one in which you can attend your own funeral (sign-up list too long). In one truck, people lounge in two long lines of rocking chairs, while a guy dances behind a neon-lit scrim. In another, a teenage slumber party, complete with manicures and PJs. In another, we are encouraged to “Make It Happen,” by signing up on a clipboard and coming back in 30 minutes, at which point they will write our goals up on Post-Its and stick them on the whiteboards and marker charts covering the walls. Or something like that—as in real life, we neglect to follow up on our burgeoning potential.

Touts call from the back of every truck, offering services. “Get mentally cleansed at the apothecary’s spring cleaning!” “Star in your own movie—flee monsters in front of our green screen!” “We have cupcakes!”

Working our way back to our car, we attempt to enter a truck with shiny white curtains, but a suited fellow with a headset stops us. “You can’t go in here,” he says. “If you want to find out what’s in here, you can look in two trucks down.” In that truck, we find a mob of people watching a wall of 14 television screens. The video feeds on the screens monitor the interiors of the two closed-off trucks from various angles. We watch a hapless woman, culled from the crowd, meet with a “scientist” and a “professor” and be handed a briefcase and charged with an important mission. When she finally arrives in our truck with the briefcase, she is greeted by a truck full of screaming, clapping people. (The briefcase holds more cupcakes.)

The final truck we visit is built out in black-and-white wood cutouts of Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, etc., with openings for people to put their faces and be photographed. A simple concept, but well executed. By this time, I am beginning to appreciate the particular aesthetics of tricking out the back of a box truck. The best artists use all of their available space in especially novel and efficient ways, making the box trucks seem big and deep, snug and compact, or cluttered and energetic, according to their functions—a fitting challenge for New Yorkers, who are always trying to do the same to their tiny apartments.

“Hey, you five!” the photo cutout truck’s proprietor, a woman in a long silver-spangled evening gown, hollers at us. “Hop up in there and let my stupid asshole gay boyfriend take your picture!”

Happily, we obey.

New York, New York

At the Night Market

On a moonlit street in Brooklyn, merchants open the doors of their trucks and welcome an audience armed with curiosity and cupcakes.