Not many folk would go out of their way to find a mud spring in a lonely English field, but Ella, the borrowed black Labrador Retriever, knows that I am one of the few.

When I tell her what today’s adventure will entail, she is, at first, nonplussed.

“Mud springs?” she says. “Why in Dog’s name would we go and find mud springs?”

Because they are special, I tell her. They’re a geological wonder, heard of by few and seen by fewer. They sit at the edge of a farmer’s field just a few miles from here, and we owe it to our future selves to find them.

“My future self would be perfectly happy with a nice biscuit,” Ella snorts.

As we walk out the door we meet Jeeves, the cat from over the road.

Ella tells Jeeves, “He’s taking me on another one of his wild goose chases.”

Jeeves gives her the kind of questioning glance that only cats can give. She leans closer and whispers in his furry ear: “Last time, he took me to a river with a ball, and the ball just disappeared.”

She jerks her eyes in my direction, like I’m the crazy one with the tail.

“Would you like me to come along too?” Jeeves says. “Liven things up?” He flicks his tail in a manner that tells other cats that he is being sarcastic, but since Ella is a dog and I am a human, we don’t care.

Jeeves, you can’t come, I say.

“Heartbreaking,” says Jeeves. “Your adventures always sound ghastly.”

“This one’s about mud, apparently,” Ella points out.

Ella and I jump in the car and drive away. Jeeves smirks and watches us leave, his tail flicking in a manner that suggests to other cats that he thinks we are even more foolhardy than we look.

“This isn’t about losing data. It’s about someone else gaining access to your data. Backups won’t be worth a cat’s ear when that happens.”

A few minutes later, from the back of the car, Ella says, “What do you make of this iCloud business, then?”

I say I’m not sure what you mean.

“Apple’s timing was terrible, if you ask me.”

How so?

“So soon after the Sony PlayStation hacking?”

I open the car windows, and Ella sticks her face into the breeze, drinking in air. She continues, “The biggest problem with this cloud computing thing is security. Everyone thinks that just because a company is one of the biggest consumer brand names around, its online security is going to be top-notch. But look what happened to Sony. What a mess.”

Ella shakes her head. “I really missed the PlayStation Network,” she adds. “That outage was a nightmare. Twenty days, and no one to play Little Dog Planet with. Finding other things to do felt like hard work.”

Oh come on. You’re a dog. You have no idea what hard work really means.

“Pfft. You’re a freelance writer, neither have you.”

We engage in mutual sulking, then Ella carries on.

“It’s about trust, isn’t it? Who do you trust? Who can you trust? And how much of your data are you willing to entrust to those people?”

Yes. It’s always been about that.

“You trust Google with your email, for example. And with other stuff.”

True, I do. They look after it all for me. But that’s the same with any email service. You have to rely on someone else to manage it all. You have to put your trust somewhere.

“But that’s it—can you depend on them to keep getting it right? What if Google one day has a PlayStation moment? What if someone finds a way to get their hands on all those Google IDs?”

I have backups.

“Who cares? This isn’t necessarily about losing data. It’s about someone else gaining access to your data. Or using your identity, pretending to be you. Backups won’t be worth a cat’s ear between the teeth if that happens.”

Cat’s ear between the teeth?

“It’s a dog saying. Are we there yet?”

Wootton Bassett is famous for standing still when the bodies of dead British soldiers are repatriated from Pakistan and Afghanistan. Planes land at nearby RAF Lyneham, and the dead are driven along Wootton Bassett’s High Street en route to their final resting places. Hundreds of townsfolk routinely stand silently by, somberly honoring the dead.

So much grieving’s been done here that the Queen thanked the people of Wootton Bassett by giving the town the prefix “Royal”—and so Royal Wootton Bassett it shall become, later this year.

But what I’m more interested in is a strange geological accident a couple of miles south of the town centre.

At the edge of a field, a stone’s throw away from the London-Bristol railway line and the now abandoned Wilts & Berks canal, there’s a dark, wooded spot known locally as Templar’s Firs.

Here we will find mud springs. Three domed blisters of ground covered with a thin skin of hard earth, underneath which lurks a bottomless pit of cold, grey, oozing mud.

The tales you hear of these mud springs vary from unlikely to absurd. They have been known to vomit up fossils from rock layers deep underground, it’s been said. They have, in times past, swallowed unwary cattle. In the 1990s, 100 tons of rubble was poured into them in an effort to seal them up for good, but every last stone sank forever. The mud still oozes upwards.

We started this trip with only a vague idea of where to find the mud springs, and it turns out to be harder than I expected. We’re looking for a small patch of trees, but there are small patches of trees in every direction. We’ll have to try them all, one by one.

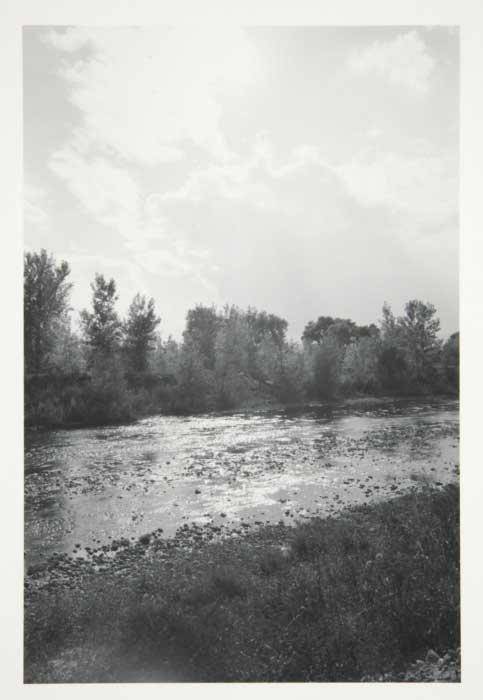

A path runs alongside what’s left of the canal. No longer navigable, it’s home to lots of birds and weeds. We see a heron, a nesting swan, lots of moorhens and ducks. It’s quiet and peaceful here. We’re almost alone, except for a couple of other dogs walking their humans.

I call Ella to heel, worried that she might suddenly get sucked down into the netherworld with a yelp and a gloop. Too late.

Ella pipes up again.

“My point is, you just can’t trust anyone else with your data. Not if you want to take care of it.”

But there’s data and there’s data, I reply. I throw a stick, and Ella ignores it.

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

Well some of it matters and some of it doesn’t. The important stuff—things like online banking—is the kind of data No one could handle by themselves anyway. You have to place a certain amount of trust in big companies, just to get by.

“Fat lot of good that did for PlayStation Network users,” Ella sniffs.

You’re really annoyed about that, aren’t you?

“Dogs can be gamers too you know,” she snaps. “A lot of us love games. Some of the world’s best ever games were about dogs. Parappa the Rapper, for example. Almost all the supporting characters in Star Fox. Nintendogs. Poochy from Super Mario World 2.”

She stops for a moment, her tail wafting in a morose sort of way. “No one ever thought to design game controllers for paws, you know. No one.”

Fair enough, I say. Anyway, the Sony security story came at a bad time. But it’s not going to stop the world moving towards online storage. It’s an inevitable result of people owning more than one computer.

“You humans are so greedy.”

Yes, we are, I admit. And when we have a computer and a phone and a tablet and a set-top box, and Dog knows what else that will be invented in the next few years—when you have all that stuff, you won’t want to have to think about keeping it all in sync. Managing files across multiple gadgets is a nightmare. Apple invented iCloud because they knew that people would stop buying sleek iGadgets if they didn’t.

“And you trust them? You think they’ll be able to keep it all secure? Like Sony did? You think it will work? Need I remind you about dot Mac?”

Ella looks up at me, her lovely Labrador brown eyes keen and questioning. She’s deadly serious and dogly stubborn. She won’t take Yes for an answer.

Before I can think of a sensible answer, I spot a path of trodden-down vegetation leading into what looks like an ordinary clump of trees. This must be it. There will be mud.

Ella marches ahead, where we can see a barbed wire fence hidden in bushes. The only thing around here worth fencing off so substantially must be a potentially man-eating mud spring. I call Ella to heel, worried that she might suddenly get sucked down into the netherworld with a yelp and a gloop.

Too late. Ella’s already on the other side of the fence. She’s wriggled through a gap.

Come back over here Ella. It might be dangerous in there.

“It’s fine, honest,” she says. She sniffs the air and pads about. “The ground’s solid.”

Getting closer, under the shade of the trees, I can see the fenced-off area more clearly. Within the trees lies an odd, empty patch of ground. It looks unusually green, as though covered by fine moss. Is it me, or is it—glistening?

“I’m like a global technology company who has betrayed your trust and lost your stuff in a virtual mud spring, and now I’m apologizing.”

This is it, Ella. We’re here. The mud springs.

“I know,” she says, looking around and heading onwards toward the glistening patch.

Ella, heel. Come back. Really, I mean it.

“Oh for heaven’s sake,” she says, exasperated. “I do have four legs, you know. I can cope with mud. Much better than you can.”

I know that, I’m sure you’d be fine. But you’re not my dog, I’ve borrowed you. Your owner would never forgive me if I allowed you to be swallowed by a bottomless quagmire during walkies.

Ella tuts in frustration, but she understands my point, and returns to my side. We walk around the edge of springs, peering in at the fence at the dense undergrowth. Every now and then we spy an overgrown yellow warning sign, yelling at us: “WARNING: MUD SPRINGS. RISK OF ENTRAPMENT.”

“Entrapment” sounds tame compared to “being pulled downwards into cold everlasting blackness, forever screaming your regret at climbing that fence”—but that would have needed a much bigger sign.

I stand for a while, taking it all in. Ella sits by my feet, impatient to go somewhere more interesting, keen to argue the case against cloud computing some more.

The birds sing. We listen to another train passing. Maybe I’m hoping to hear a plop of mud, or the shriek of a careless wild animal being sucked down to its doom. But all we hear are very ordinary English countryside sounds.

Ella’s sat down, panting, her tongue out.

“Can we go now?” she pleads.

Aren’t you interested in mud springs? I ask.

“Not really. Not at all, actually.”

Perhaps she notices my slightly crestfallen expression, because suddenly she jumps up on all fours and wags her tail.

“I mean I do. I love mud springs when they involve walks. And this is a walk, so it’s great!” she gushes.

You’re just saying that.

“Yes I am, but who cares? I’m trying to make you feel better. I’m like a global technology company who has betrayed your trust and lost your stuff in a virtual mud spring, and now I’m apologizing.”

Now you’re just being silly. If I throw a stick for you now, will you fetch it, like you’re supposed to?

“Yes, Dog almighty yes! Come on. Let’s leave the mud to be squelchy to itself, and let’s worry about online security and cloud computing another day.”

I turn and wave to the humdrum ordinariness of the mud springs. We’ve found you now, I say. Our future selves are pleased that we did.

“My future self would still quite like a biscuit, though,” Ella reminds me.

Come on then, Ells Bells. Let’s go and find you a biscuit.

Her eyes are wide with astonishment. She can’t believe I called her “Ells Bells.” But we trudge away to seek out biscuits in less muddy places.