Punishment seems meted in series this season, poor Haiti. Back-to-back storms and copy-cat collapses. Are they bracing now for the spate of kidnappings? Ah yes—they already have those.

Last week I thought: 89 dead? Really? Couldn’t the hilltop tragedy have been a miraculous disaster—one where the school full of young bodies collapses but the young bodies don’t? I thought: why not a near brush, in which the kids walk away, their biggest problem being that they are out of school again. Left to their own devices. Truancy, not trauma! I thought.

And yesterday, as if in answer, down came portions of the school called “Grace Divine.” None of the students were killed. Divine Grace, in answer to strange prayers I would now take back, being somewhat more reliable than “La Promesse,” which was the name of the school that collapsed last Friday, killing 93.

Those roads winding their way up the mountains to Petionville are lined with schools. The roads have few sidewalks; the schools have few rooms. Many are no much larger than the lotto shacks and beauty salons that stand alongside them. You only know they are there because of a small painted sign saying, perhaps, “Jean-Etienne’s Academie” with a phone number and an arrow pointing up a torn-up road. La Promesse was a bigger school, with 700 students. In Haiti, where the vast majority of schools are private, education is a business, not a service. Which is why they’ve arrested the man who owns the Petionville school that collapsed on Friday—a large well-established institution run by the church but maintained, apparently, by no one.

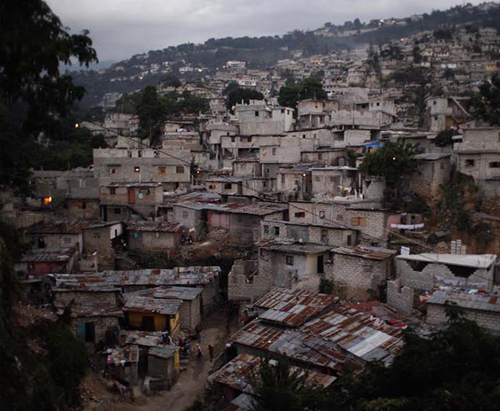

Those roads winding their way up the mountains to Petionville hug deep valleys. All along them are the concrete floors and ceilings that comprise urban Haitian dwelling on the cheap. Between the floors and ceilings are lines of drying laundry, open space, a sleeping baby. And there are, of course walls; except when there aren’t—and then there’s maybe, some rebar; unless there’s not. Then there’s only the laundry, the chairs, the sleeping baby. And you wonder, what keeps those houses up? Except for the one below?

That’s what the President of Haiti meant when he commented on the school collapse in Petionville. He said, “It’s not just schools, it’s where people live, it’s churches.” Haiti lives suspended in the elements—floating on a flood plain or clinging to a cliff-side. Homes with solid foundations find them buried in mud. Last month in Gonaives it was four feet of mud. Families there are still living on rooftops, more concerned with holes in the plastic tarps than with support rods in the walls. If they weren’t on their roofs, they were living—guess where—in schools and in churches. So President Preval speaks for the nation when he says it’s not just the schools of Petionville—it’s the whole damn road from the water to the mountaintop. The labored artery linking Divine Grace to La Promesse. It’s the spine of Port-au-Prince. It’s a bent-over backward country.

Petionville is the farthest reach from the sea-level slums of the capital—sprawling neighborhoods where poverty, illiteracy, disease, and gang warfare all meet in the capital’s run-off. Petionville is Port-au-Prince’s other axis—the summit where the gracious estates of the Haitian oligarchs and the UN brass are hidden behind gates and greenery.

Also in Petionville live the men and women who cook in the mountaintop kitchens and chauffeur up the winding roads. They live in shantytowns of stacked houses of cement, rebar, and crossed fingers. Sometimes, given the lack of trees and walls, the residents of these lesser neighborhoods have an even better view of the city below than the moneyed houses with their jutting terraces and solid doors. Who were the children in La Promesse? What kind of Petionville houses did they live in? Structures more or less secure than the school they attended? In rooms with views of the sea or of the trash-filled gorge separating them from the elite?

The relentless misfortune of Haiti goes unnoticed beyond its eroding coastline. It takes a lot to make us rubberneck at its mess.Haiti being low on resources, the people of Petionville came out with their picks and shovels to remove the bodies from the collapsed school. Yesterday the same crew of rescuers—professional and pedestrian, aunts, uncles and blue helmets—scampered back down hill to the second school, certain in the hurry of more grief.

The relentless misfortune of Haiti goes unnoticed beyond its eroding coastline. It takes a lot to make us rubberneck at its mess. Riots and back-to-back storms were a good start. Children choked in the debris of their day is an ambitious follow-up punch. I’m still struck by the deceit of these disasters: how dare they strike Divine Grace, to which children arrive in the morning on tap-tap trucks bearing overt faith in the Lord. And how dare they call themselves Hannah, Fay, Gustav. Please. Only “Ike” hinted at menace, in fact delivering the least damage of them all.

At least, in its perpetual state of emergency, Haiti is full of aid workers and doctors without borders ready to patch up school-battered children. At least the search and rescue guys from Fairfax County were already in country.

Or maybe there’s only this: at least the combined death toll of falling schools in the capital of Haiti has not hit 100. Schools come down in earthquakes and there are thousands dead in Pakistan, hundreds of parents mourning their only child in Sichuan. You won’t see that in Haiti, with its abundance of children and shortage of schools. And if a new school rises from the rubble of La Promesse, let’s hope the most promising thing about it isn’t the view. Let’s hope for something more solid even than Divine Grace.

Letters From Haiti

The Spine of Port-au-Prince

Following last Friday’s heartbreaking 93 deaths, another Haitian school collapsed yesterday, injuring nine. Our woman in Haiti shows what street-level looks like in Petionville.