Most of my second day in Jammu is spent sitting around waiting for everyone else to arrive for the wedding festivities. When relatives do show up they corner me and demand, in a mix of Kashmiri and English, why I don’t speak Kashmiri. Unless there is someone around to translate, I shrug, saying, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” and furtively edging away.

At one point a much, much older cousin (my dad is the youngest of seven siblings, his eldest sister a full 25 years his senior) with a bald head and the signature Malla proboscis (hooked, vaguely Semitic) asks me—as some sort of representative, I imagine—why there are so many Kashmiris living abroad. “Our home is here,” he tells me. In his voice is something sad. “Why do you people go so far away?”

A panel of distant relatives confronts me next, demanding to know when I plan to marry. My trademark shrug goes over poorly. “So you just date girls until you find someone?” I tell them, foolishly, “Yes,” and when asked if I plan on marrying a Westerner, I shrug again. At this I am dismissed, and the conversation switches to Kashmiri, punctuated by occasional baffled glances my way.

Finally, when I begin to feel that I can’t disappoint my family any further, an uncle, gigantic and hopelessly deaf, comes up to me and announces in a voice like a trombone, “Pasha Malla!” He shakes my hand, yells my name again, steps back and proclaims, “The last of the Mallas!” I search his face for awareness of the bleak future this entails. Instead, I see warmth and pride. Immediately, this uncle becomes my favorite; he seems to have some sort of blind (and deaf) faith that I will somehow—despite my lingual failings and geographical distance and fucked up love life—succeed at single-handedly perpetuating the family legacy, such as it is. His confidence almost makes me believe it’s possible.

The last arrival of the day is my cousin Pinky. I avoid seeking her out to inquire about our potential trip to Kashmir, but she finds me to let me know it isn’t going to happen, anyway. I try to ignore the relief I feel about this. “I’m doing a pilgrimage instead,” she tells me. Later, another cousin tells me that Pinky has opted to do this “pilgrimage,” which scales a nearby mountain and is normally undertaken on foot, by helicopter.

Pinky has errands to do and asks me to come along. Our first task is to get her mobile phone operational: The State of Jammu and Kashmir runs on a completely autonomous telecommunications network from the rest of the country. The crackdown on terror involves monitoring phone records and strategic wire-tapping, and at the plywood shack, previously a barber, that serves as a mobile center, Pinky discovers that replacing her SIM card will require an extensive background check and a passport-sized photo to create an identification badge. It will be two days before her mobile is up and running, so Pinky decides to forgo the whole procedure and tough it out until she’s back in Delhi—or any other Indian state, where her phone works just fine.

With no facility in either Hindi or Kashmiri, I am terrified that if I am confronted, my stupefied silence will be interpreted as tight-lipped guilt. Our next stop is the Jammu airport, where Pinky wants to try to make changes to her return flight. My dad has described this place as having more intense security than anywhere in the Middle East—the legendary fortresses of Israel included. The airport is barricaded with a thick concrete wall topped with broken glass and hedged with menacing spirals of barbed wire. Cars are not permitted anywhere near the terminal building; Pinky’s driver drops us off and we shuffle down a bomb-proof walkway with snipers watching us from turrets above. At the gate is an initial checkpoint where we pass through a metal detector; anything on our person goes through an X-ray machine and we are frisked at gunpoint. I have two double-A batteries in my pocket confiscated; later, my Uncle Jawahar tells me that I was lucky not to be taken into questioning, as these are often integral to any self-respecting Jihadi’s toolkit.

The actual terminal is swarming with armed guards, moving in patrols or lounging in the shade. While Pinky goes up to talk to someone at the Jet Airways ticket counter, I sit on a bench and do my best not to look suspicious. With no facility in either Hindi or Kashmiri, I am terrified that if I am confronted, my stupefied silence will be interpreted as tight-lipped guilt. I try to look at nothing. Instead, all I can see is guns and the khaki fatigues of soldiers and police. When Pinky breezes back up to ask me if I will run out to the car to fetch her wallet and try to sneak back into the airport, I have to tell her: No.

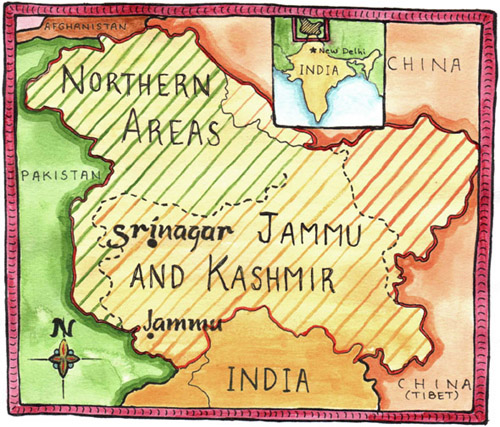

As the day ends, my sister, Cara, and her boyfriend, Yonnas, arrive from the hotel where they had been dropped off, and presumably forgotten, earlier that afternoon. Yonnas, whose family escaped Eritrea during the 1980s, appears wide-eyed in the garden. “This place is fucking terrifying,” he—someone who has grown up amidst civil war—tells me. “What the hell is going on here?” I have to admit that I don’t really know. Cara and I attempt to explain the situation in Kashmir as we understand it. We tell him stories our dad has told us, of Hindus and Muslims living in peace until militants hijacked the issue and the KPs (Kashmiri Pandits, such as my family) were forced out.

But I have to admit that, beyond a few facts, neither my sister nor I know very much. I have no idea what really happened. I have a vague idea of what Kashmir used to be—”the most beautiful place on earth,” a paradise where everyone got along and read books and played cricket and splashed about between the houseboats on Dal Lake. And maybe it was. But, really, it could be anything my family wants it to be, now. Kashmir has been relegated to the imaginations of so many of its former Hindu residents. They can’t go back to verify if what they remember is right—the reason, I think, even beyond the threat of militarism, that my own father hasn’t returned in more than 20 years. Would he find the place he wants to be there?

Later that evening with the sun going down, I sit with a cluster of uncles in the garden digesting a meal of paneer, rogan josh, lotus stems, and various overcooked green vegetables. Like a chorus of bullfrogs, they take turns burping. I ask them, these wizened, belching patriarchs, if there’s any hope of KPs resettling in the Valley. They exchange looks. “For visits, only,” says the bald older cousin with the impressive honker. “But never to stay,” adds an uncle—a slender, pensive one. The rest, even the deaf giant I like so much, murmur in agreement. And then it’s quiet. We sit, listening to the buzz of the city punctuated with one other’s gas, as night falls around us like a cloth draped over a birdcage.