From Delhi I fly to Bangalore. I will be staying for a few days with my sister in the guesthouse she and Yonnas share with four twentysomething entrepreneurs from France, here in India to ply French wine on the burgeoning middle-class. Bangalore is known as The Garden City: There’s plenty of green space and a big central lake that nearly looks swimmable, but it is choked by traffic due to the recent tech boom that has exploded the city’s population. Still, there is something I like about this place, the hub of India’s IT industry—although it might just be the Western feel lent by all the cafés and restaurants. Also, after Delhi, it almost seems clean.

My first night in Bangalore, I meet one of the supposed faces of new India. His name is Ajay, and he is a friend of the French wine-dealers. Ajay is 25 and runs some sort of bluejeans-smuggling operation that has him jetting back and forth to Thailand every few weeks. Dressed to kill in strategically faded denim and a designer T-shirt, Ajay invites us and Team France (three guys and a girl, Sophie) to a five-star hotel bar with a waterfall, palm trees, and phosphorescent blue lighting. He has a degree in economics and tells me, on the way to the bar, “I was going to do my MBA, but when I graduated I wanted to make as much money as quickly as possible.” So, naturally: jeans.

Ajay spends most of the night on his cellphone. I get drunk and chat with my sister and Yonnas, while the French move around the bar extolling the virtues of Beaujolais to local yuppies. When the place closes shortly after midnight, they compare the business cards they have collected over the course of the evening. Meanwhile, Ajay is on his phone arranging for taxis, booze, and food. As we head back to the guesthouse, he instructs us on his plan for the rest of the evening: “We’re going to drink all fucking night!”

At my sister’s place, beer and butter chicken are waiting for us; we eat and—sure, why not?—keep drinking. Despite the presence of a perfectly good stereo, Ajay insists on playing music through some sort of BlackBerry-type device—a “party mix” of Bollywood hits and top-40 American pop—and wiggling his hips in front of our faces.

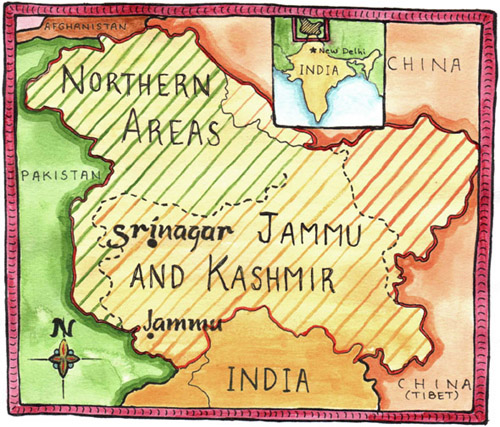

Sporadically, Ajay takes interest in me and my sister, but only to ask us questions that seem designed to demonstrate his knowledge of America. “Have you been to Cleveland?” he wonders. Cleveland? “To see the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.” But then Ajay discovers that we have Kashmiri roots. “Kashmiris are the best-looking people in India,” he fawns. “They’re the smartest, the best sportsmen, and… the best looking.” Meanwhile, the French are off in a cluster in the corner. With only two bedrooms and three beds between the four of them, they rotate bunking assignments, and they appear to be shooting fingers to see who has to (or gets to) sleep with Sophie tonight.

Ajay goes on to explain how Cara and I are to be envied for our light complexions; apparently he is looking into bleaching his skin to get closer to what he considers some sort of beatific ideal. The French, who move as a unit, are now standing, nodding to us sleepily, and heading up to bed. Ajay, oblivious to their goodnight wishes, is telling me how he’s going to dye his hair blonde. “But just in the front? In a, you know, stripe.”

By now it’s four in the morning, and soon Cara and Yonnas follow their housemates up to bed. My sister, eyeing Ajay seated beside me, asks if I’m OK sleeping on the couch; pointedly, I tell her yes. Then I am left in the living room of the guesthouse with Ajay, sitting in the dark, waiting for him to stop telling me how good looking I am and call his driver and leave.

The next morning, I wake to the French roommates bustling out the door, off to make some sort of deal on a case of Chablis—except Sophie, who is still sleeping. By the time she wakes up, everyone, including Cara and Yonnas, is off to work. Sophie and I chat for a bit, although it’s hard to get a conversation going when she checks her cellphone for messages every few minutes.

We both decide to head into the city—me to do some looking around, her to try to track down her pals. I tell her that if she can’t find them, we should meet up for a coffee and come back to the house together.

“I was going to do my MBA, but when I graduated I wanted to make as much money as quickly as possible.” So, naturally: jeans. After bustling around for a bit, I arrive at the café at the agreed-upon time. It’s obvious that Sophie wasn’t able to find her countrymen: She’s set up alone at a table right on the street, already sipping from a bowl of something frothy, looking around. The music playing inside is the sort of stuff you’d expect to hear thumping from a lowered Honda Civic. I order a coffee, take it out to the patio, and sit down.

We chat for a while and the conversation is fine. Beyond her intense dedication to the wine-selling project, Sophie’s actually very personable and fun—and she makes a point of assuring me that “nothing happened” between her and her friend the night before. She’s pretty, and this seems encouraging, so I try to seem interesting by telling her things about India, but considering that I don’t really know very much, that tact goes nowhere. Then we’re done with our coffees and it’s time to head home.

This is when Sophie notices that her purse is gone.

The purse had been on the ground by the leg of Sophie’s chair. Clearly, someone walking by has grabbed it. Everything was in that bag, she tells me: wallet, ID, credit and bank cards, iPod, camera, phone, a few thousand rupees—and her passport. Realizing this, Sophie starts screaming obscenities in French. She actually wrings her hands.

After a steady minute of “merdes” and “putains,” Sophie calms down enough to suggest going to the police. Law enforcement in Bangalore probably has bigger worries than tracking down a French entrepreneur’s handbag—but telling this to Sophie, now crying, isn’t an option. What I realize, though, that for the first time since I’ve been in India, I can be of some use. Compared to Sophie, whose limited English is sure to prove a huge handicap in dealing with the cops, I’m almost competent. To the police station, then, I offer—already leading the way. Finally, a chance to shine.

The police station is a rundown shack off one of Bangalore’s main downtown thoroughfares. As an officer seats us in rickety wooden chairs at the sergeant’s big desk, I half expect a goat to appear from somewhere and start gnawing on my pantleg. Instead, a big, beaming man in the standard-issue cop moustache trundles into the room and stations himself behind the desk.

“What is the problem?” he asks, looking from me to Sophie (bleary-eyed, sniffling) and back again.

I begin to talk, and the sergeant holds up his index finger. “Uh-uh-uh,” he chides me. “Must first fill out report.”

As an officer seats us in rickety wooden chairs at the sergeant’s big desk, I half expect a goat to appear from somewhere and start gnawing on my pantleg. He slides a piece of triple-layered carbon paper at me, and I do my best to write down what happened in the space provided. In the meantime, a waiter appears from somewhere bearing two juice boxes on a silver tray. “Cold drinks,” explains the sergeant.

When I am finished with my statement, I hand it over for approval. The sergeant glances it over and shakes his head. “No, no, no,” he says. “You have written that the madam’s bag was ‘stolen’—did you see someone steal it?”

“No, but—”

“Then, no, you write ‘misplaced.’”

As I watch him rip my report in half, I try to explain that it clearly wasn’t misplaced. Sophie looks bewildered. “You write, again.” The sergeant grins like he’s having the time of his life and passes me a fresh form.

My next attempt receives the same rejection, and I have to convince Sophie that I’m fine, that I know what I’m doing and that, no, she doesn’t need to do it. But then the sergeant comes around the desk, stands behind me and, with his hands on my shoulders, proceeds to dictate. He begins with the date, and then moves on to the weather. “It was a sunny day,” he says, closing his eyes for inspiration, “and my companion and I were enjoying our coffees.” When I hesitate, he squeezes my shoulders, so I write down what he says, word for word, until the sergeant’s account of the robbery is committed to paper. He looks it over, satisfied, and files it into a box marked “Records,” where—even Sophie realizes now, I’m sure—chances are it will never be looked at again.

That night Cara, Yonnas, and I go to an after-hours club. Because Indian bars close by midnight, “after-hours” start at eleven. The club is in the basement of a shoe store; there’s actually one of those doors with a peephole that slides back to reveal a pair of suspicious eyes. We don’t know the password, but, after a lookout on the street gives the all-clear, we’re let inside anyway. Yonnas suspects it’s because Cara looks white.

Straight Indian men dance together as they would with members of the opposite sex—and, apparently, if they were extras in a Ginuwine video. The club is low-ceilinged, with a central disco ball and a few spinning lights. A DJ in a Yankees cap plays bhangra, Bollywood and American Top-40. The crowd seems to be exclusively male—although once my eyes grow accustomed to the dark, I realize that this isn’t exactly true. Guys crowd the dancefloor while the women hang back, moving quietly to the music in the shadows.

The men dancing are intense: dudes wine up on one another, grind asses into thighs, bend over for spankings. “Is this a gay bar?” I ask Cara. “No,” she replies, handing me a beer, “it’s just like that here.” She explains that while public acts of male-female sexual contact are still frowned upon, straight Indian men dance together as they would with members of the opposite sex—and, apparently, if they were extras in a Ginuwine video. I’ve seen these public displays of affection between Indian men before, and know that they’re meant to be platonic (homosexuality, ironically, remains very much taboo). Still, the guy rubbing his face into another guy’s crotch seems a touch beyond camaraderie.

That night, I end up in bed with Sophie. I’m not sure how this happens, exactly—Cara, Yonnas, and I come home to find Ajay passed out on the couch, and for whatever reason the French Four figure that the best place for me is in their female compatriot’s bed; one of them will crash on his Thermarest on the floor.

As Sophie brushes her teeth in the en suite, I lie in her bed, trying to figure out appropriate sleep-attire—boxers? Jeans? With a mouthful of toothpaste, Sophie thanks me effusively for my help that afternoon. She spits. The French Consulate, she explains, has stepped in and already issued her a new passport, and it turns out most of the missing stuff is covered by her travel insurance plan.

“Oh, good,” I say, pulling off my jeans—but quickly shooting under the sheets. As Sophie emerges from the bathroom in pajama bottoms and a tank top, turns the lights off and slips under the covers, I realize that I haven’t had a moment of anything approaching intimacy since arriving in India. I have to admit that, before coming, I had notions that my status as a Westerner would make me attractive to America-obsessed Indian women. The reality is that they haven’t given me a second look. And here I am, now, in bed with a white girl.

Oh, well. I decide to make my move, and shuffle over a bit so my feet are touching Sophie’s. She responds by rolling away. I lie there for a moment, staring at her back. Within minutes she is snoring.