My second day in India is one of intimacies, begun innocuously enough with a trip to Jama Masjid, which my aunt’s personal assistant, Raju, claims to be “the biggest mosque in the world.” (It is not.)

Still, the mosque is very fine, rising austere and pristine from the surrounding Old Delhi squalor. Sprawled out front on the pavement is a man with what appears to be a leg growing out of his chest. His eyes are glazed; he stares blankly ahead at nothing, a foot wagging below his chin. “Mr. Pasha!” hollers Raju. “Come see the mosque.” Guiding me by the elbow up the steps, Raju reminds me of the host of a fancy party who has discovered a guest opening the shower curtain to find a bathtub dripping with mildew.

At the entrance to the mosque I am given a cloth skirt to cover my legs, and I leave my flip-flops in the care of a guy surrounded by a cloud of flies. When we return, Raju looks angry and we reclaim our shoes without leaving the chappal-wallah the requisite tip. “He thought I was your tour guide,” he tells me on our way to the car. “He didn’t know we are…” his voice trails off before he adds brightly, “friends!”

For lunch we stop at a place with an all-you-can-eat pasta bar. The décor is quintessentially East Side Mario’s: red, white, and green tablecloths, photographs of Sicily, piles of plastic tomatoes everywhere, waiters in Chef Boyardee outfits (replete with Super Mario moustaches). From a menu that features lasagna, ice cream, and tandoori chicken, I order a pizza. It arrives steaming: The dough has been molded into the shape of a heart, and the mushrooms spell out the word LOVE.

Facing too much pizza for one man, I ask Raju if he’d like to share. I give him the L and O side, and start in on V myself. Raju stares at the two slices for a moment, then picks out the mustard from the basket of condiments on our table, scrutinizes its ingredients label, and proceeds to squirt a network of yellow lines over the cheese. Then, ketchup. We eat in silence—me, the tourist, and Raju, this man who is being paid to be my friend and has inappropriately dressed his pizza; together in silence we eat the heart-shaped pizza of LOVE until it is done.

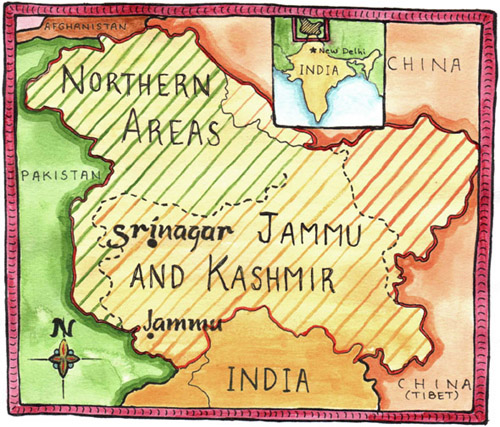

After lunch, my next stop with Raju is the Old Fort, where at the gate I get into a funny argument with the ticket taker about being an Indian national (paying a five-rupee entrance fee versus the 150 rupees it costs for foreigners). “You’re not Indian,” he tells me. “Sure I am,” I say. “I’m Kashmiri.” He looks at Raju, then at me, and says, “I’m Kashmiri—would you like to speak Kashmiri with me?”

One hundred and fifty rupees later, we are walking alongside what I imagine once upon a time used to be a moat. Couples are pedal-boating on the water. “My wife and I came here last week,” Raju tells me, gesturing at the boaters. “It was very romantic.” He pauses while we walk past a triumvirate of hijras, the quasi-caste of “third gender” hermaphrodites, who make catcalls at us and beg for money. Safely past them, Raju puts his hand on the small of my back and gestures at a pedal-boat on the shore. “Mr. Pasha, shall we go?” He’s so sweet about it I almost say yes.

Inside the fort, we walk around and admire the ruins, the regal mosque, the parrots flapping green and squawking from building to building. Everywhere are young couples lounging together in the shade, some kissing, some asleep in one another’s arms. Raju is visibly perturbed. When I ask him what’s wrong, he sighs. “Look at these students, not doing the study.” I probe a bit further and Raju admits that he is uncomfortable with public acts of intimacy. “They take this from America,” he laments. “What is love if you show it to everyone, Mr. Pasha? Love is between two people, not the world.”

In India, it is customary for male friends to walk around arm-in-arm or hand-in-hand, which is what they did on a walk through Central Park. And just like that I realize that time has gotten away from me again: It’s Valentine’s Day. Everything—especially the pizza—makes sense. An endless barrage of love-related programming has been playing on the radio; when we’re back in the car, there’s a debate on about the increasing prevalence of “love marriages” in contemporary Indian society.

I’ve often told my dad that if I haven’t found anyone to wed by the time I’m 35, he’s free to hook me up with a nice eligible Brahmin girl. There’s a catalog and everything, with each of the entries identified by education, career prospects, caste, and, most importantly, astrological details. That said, I’m not sure what sort of clout a self-employed Capricorn with a graduate degree in reading books (what an ex-girlfriend used to call my “stepladder to nowhere”) might have amongst prospective brides. Regardless, my dad finds the whole thing stupid. “Find your own wife,” he tells me. “I did.” Which is true, he did. Twice.

My Indian Valentine’s Day ends back at my aunt’s place. She and my uncle are still away on business, although they will return the following day. Raju goes home. I am left alone again with a single beer and satellite TV in the strange room where I sleep. I will be here one more night, and then we will head north for my cousin’s wedding in Jammu. Before I fall asleep I recall a story of my dad’s, one of my favorites.

Apparently, on his first trip to North America back in the mid-’70s, my dad met up with a pal of his from Kashmir who was living in New York City. In India, it is customary for male friends to walk around arm-in-arm or hand-in-hand, which is what they did on a walk through Central Park. As even today the notion of homosexuality is still very much taboo throughout most of India, there would have been nothing even vaguely gay about this act of intimacy; it was a display of camaraderie and little else. But in Manhattan, they were bombarded with insults—”Fags,” “Go home, queers,” etc., and had to abandon touching one another for the rest of their visit.

Thirty years later, my dad met up with the same friend in San Francisco. They hadn’t seen one another since their last encounter, and joked about their naiveté as newcomers to North America. But my dad had an idea: “I know a place where we can go,” he told his friend. Together they walked down to Castro Street, where my dad took his pal firmly by the waist. Arms draped around one another, they walked up and down the neighborhood for hours on end, and later went and cuddled up together under a tree in some park. Nobody said a thing.