Chris Jordan makes beautiful photographs he hopes will disgust you. His work, on display through July 31 at the Von Lintel Gallery in New York City, takes reports of large-scale waste and consumption out of the realm of statistics and places them squarely in front of our faces.

Chris Jordan is a Seattle-based photographic artist who portrays the detritus of our mass culture—piles of cell phones, aluminum cans, garbage, and the like. His work is exhibited widely in the U.S. and Europe, and has been featured in print media, blogs, documentary films, and radio and television programs worldwide. Chris is also a father, husband, gardener, vegetarian, sometime jazz musician, and has an obsessive fascination with the sound of large Chinese gongs.

All images courtesy Chris Jordan and Von Lintel Gallery; all images copyright © Chris Jordan, all rights reserved.

Running the Numbers uses the facts and figures of U.S. consumption as a starting point. What’s the allure of statistics for you?

I have to step back a tiny bit to answer that. The previous project I did was called Intolerable Beauty and that particular project was also about consumerism and our consumer society, but each image was photographs of random piles of things, rather than specific quantities. What I was hoping to get at with that project was the scale of our consumer society. The thing I noticed, after I’d been doing some talks and lectures, was that I was always using numbers. So I’d show my cell phone picture for example, and along with the image I would say that the actual number of cell phones that are discarded in the United States is more than 130 million. So this image only represents a tiny portion of that.

So, statistics became a way of grounding your message more deeply.

I realized one way I could do that is to show the actual quantities of things, rather than just big piles of them. The thing about that is, there’s nowhere you can go and see these actual groups of things. It’s like our entire consumer society is happening invisibly, in some ways. So, the only way we know about the staggering effects we’re having on our environment, for example, is to read scientific reports about statistics, but there’s no where you can actually go and see the numbers. The only way we have of relating to these incredibly important facts about our mass consumption is statistics. And the problem with statistics is they’re so dry and emotionless. If we’re going to be motivated as a culture to change our behavior, then we’re going to have to find a deep motivation. Because statistics are so hard to connect with, we’re not going to find motivation from them.

So, is that the difference then? An image with a fact and a statistic behind it motivates, as opposed an image of a pile of waste and consumption.

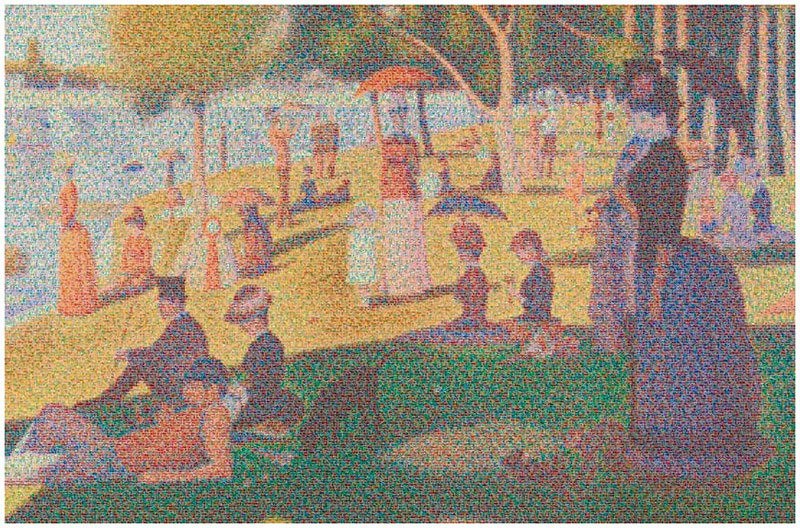

My idea with the Running the Numbers series is to provide the visual. To give you the statistic in a different way that allows the viewer to experience the number more directly with their heart. One of the huge problems that faces our society right now, is that this problem with our consumerism, and the resulting global warming, worldwide environmental destruction, the toxification of our oceans and the desertification of our agricultural lands, and so on, are not happening because there’s an extremely bad person out there who is doing a huge amount of terrible consuming. This is happening because of the tiny incremental harm that every single one of us is doing as an individual. The problem is this cumulative effect from the behaviors of hundreds of millions of individuals. Each person looks around at his or her own behavior, and it doesn’t look all that bad. What we each have to expand our consciousness to hold is that the cumulative effect of hundreds of millions of individual consumer decisions is causing the worldwide destruction of our environment. The hard part of that is the notion of the enormity of the collective.

How do you help people to understand that we can’t do anything to stop or curb pollution and consumption until we thinking about large-scale effects?

That’s what I’m trying to tap into with my work: To raise the consciousness of the viewer so that they start thinking more about the collective that we’re all a part of. That’s a major theme that resides below the surface in all of my Running the Numbers works: The relationship between the one and the many. I like people to be able to stand back and see the many and then to walk up and see the one. Whenever I speak to people about this, they always talk about how people need to be better-educated consumers, or make better decisions. It’s so hard to accept the complexity of what’s actually happening which is this incomprehensively huge society where we’re all doing it together.

How do you negotiate the concepts and ideas behind your photographs, and any attempt to create or find beauty through your work?

That’s a very interesting question. At the very beginning of my Intolerable Beauty series, I had this idea that the images had to be beautiful in order for people to be interested in them. I thought that if I made an ugly image, no one would want to see it. If I can make a beautiful image of a difficult subject then the beauty will draw the viewer in and they’ll spend some time with the beauty part and the message will sort of seep in. I went with that notion for the longest time, but part of what got me started on Running the Numbers is that when I would show my work, especially the Intolerable Beauty series, all people would talk about was how beautiful it was. I found that the beauty was actually getting in the way of the message I was trying to convey.

How so?

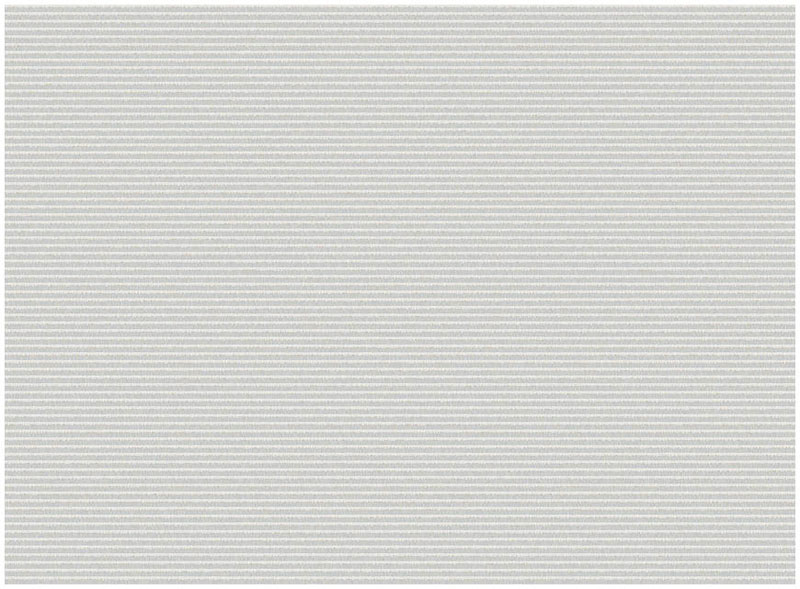

Collectors were collecting my work because it was so beautiful and galleries were showing my work because it was so beautiful and a couple times during a reception I’d want to shout at the top of my voice “Everybody, this work is about something!” So I decided to do the ugliest picture I could think of: an image of 125,000 cigarette butts. That’s the number that are littered around the world every second. I got 5,000 cigarette butts and I photographed them over and over, stirring them around, until I had an image of 125,000 cigarette butts. My intention was that it would be this disgusting, extremely edgy image. I hung it in my show and everybody flocked to that image and they were talking about how beautiful it was.

I think that for better or worse people are really attracted to art that presents something awful or terrible as beautiful.

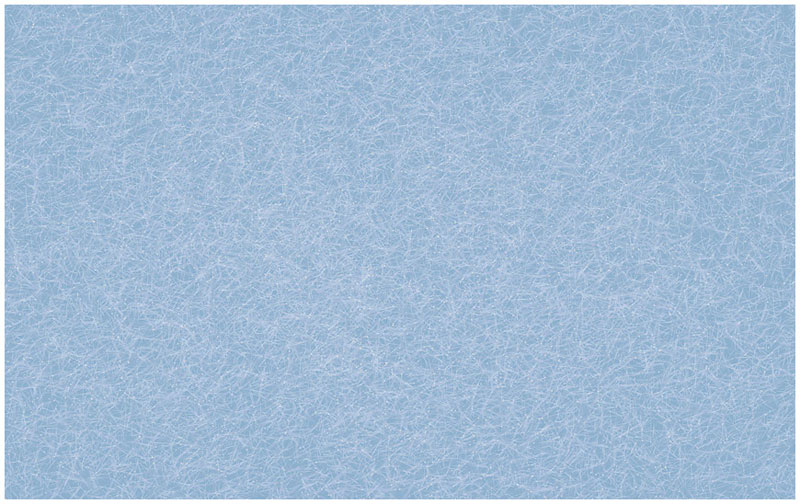

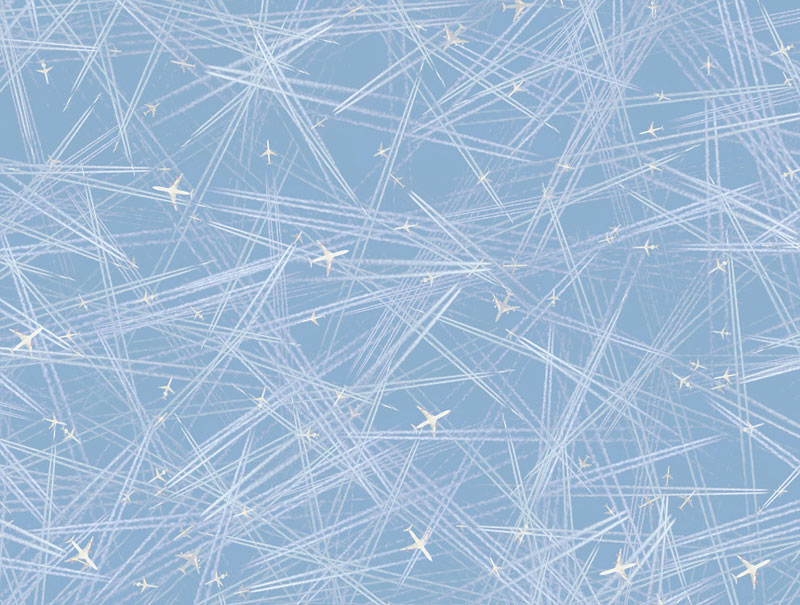

My idea of what beauty is has altered a lot in the past few years. I used to think that beauty involved a lot of color and prettiness. I now realize that, like the cigarette butts and the jet trails in my new series, things can be beautiful just for the fact that they’re complex. There’s a beauty in the fact that an image is being direct and facing up to something. It’s a different kind of beauty than Pamela Anderson kind of beauty.

What are you working on now?

I’ve got a few more in the Running the Numbers series. I want to do an image that relates to the number of unwanted dogs and cats that are euthanized every day in the U.S. They euthanize more than 10,000 dogs and cats a day. I want to find dog and cat collars, I only need a few hundred and then I’ll just photograph them over and over. I want to make a Mandala made out of cell phones; it would be my last cell phone image, that will relate to the number of highway injuries and deaths that occur because people are talking on their cell phones. There’s something like 300,000 highway injuries and 4,000 highway deaths directly attributed to people talking on their cell phones.