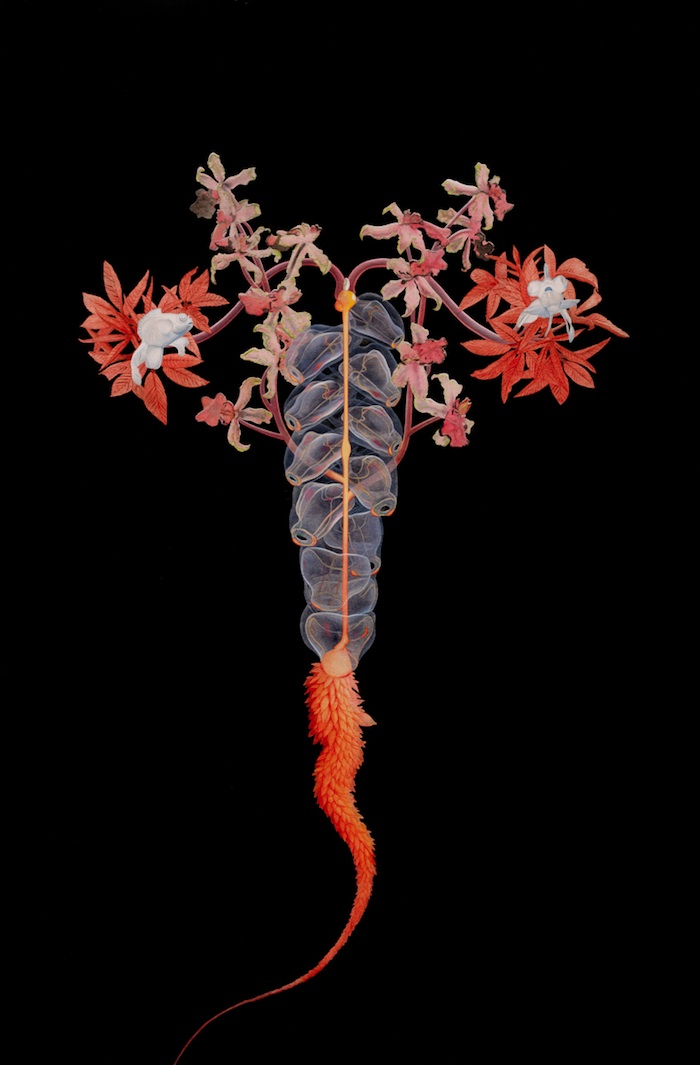

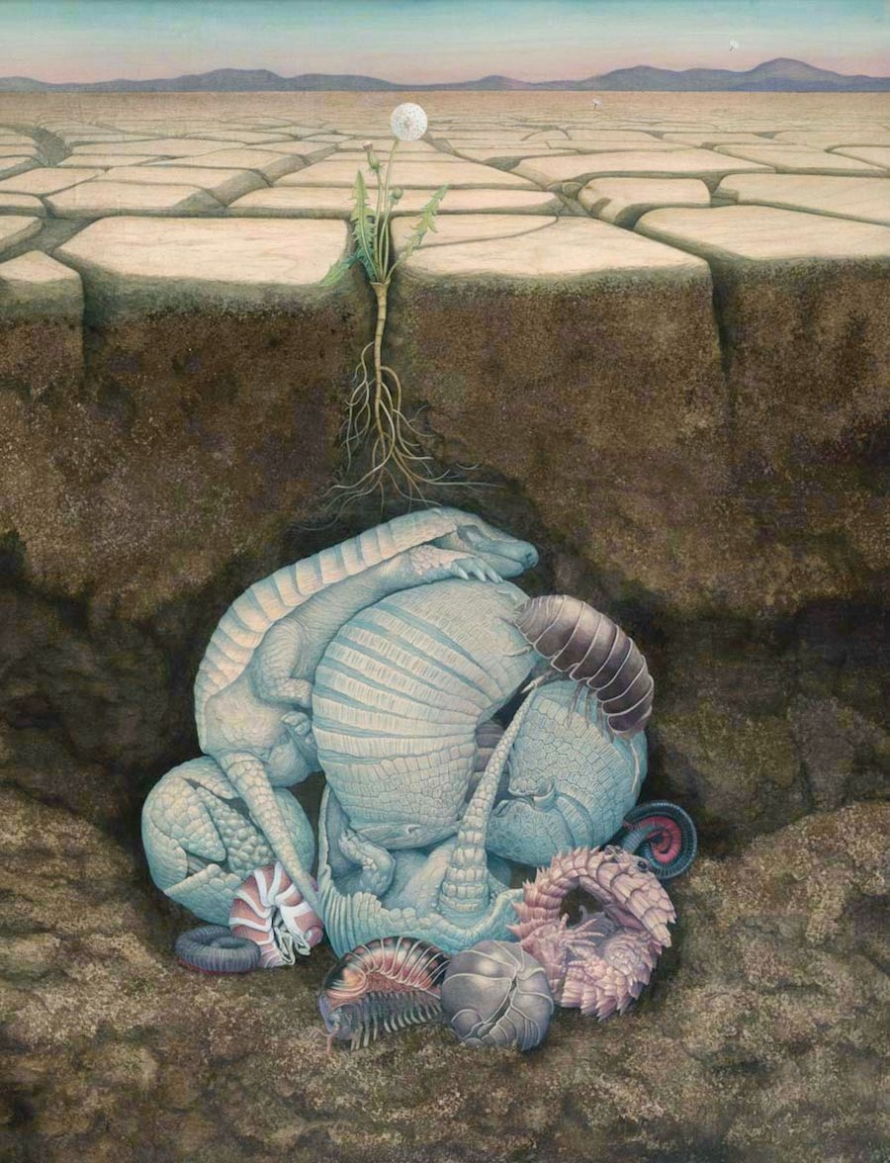

Tiffany Bozic is a naturalist of her unconscious. In her latest work, on view through Dec. 11 at Joshua Liner Gallery in New York, Bozic’s paintings combine fascination with the natural world and a desire to explore uncharted emotional territory in dream-like renderings of plants and animals.

Currently based in San Francisco, Tiffany Bozic has shown in galleries throughout the United States and Europe, and spoken at the 2007 Semi Permanent International Arts and Design Conference in Sydney, Australia. Her artwork has been published in magazines such as Flaunt, Fourteen Hills, and Alarm. Bozic was recently published on the cover of Coast Magazine, featured in Metamorphosis 2, and In the Land of Retinal Delights, The Juxtapoz Factor from the The Laguna Art Museum in Association with Gingko Press 2008. Tiffany participated in the California Academy of Sciences Artist in Residence program from November 2006-2007.

Images courtesy the artist and Joshua Liner Gallery, all rights reserved.

What’s your relationship to nature and animals? How did you come to paint them in such imaginative settings?

I can’t say I can fully comprehend my relationship to nature, but I am interested in this relationship and am hoping I will continue to explore it through my work. I usually paint familiar animals that I have had a direct experience with, either held in my hands, interacted with, or seen on my travels. Sometimes I place the critters in settings to create a story based on a particular concept or feeling.

The titles of your work are evocative—”Under my Skin”; “Oxytocin.” Do they reflect your emotional associations with the work?

I read a lot of books about instincts and behavior and as a result some of my paintings are titled after scientific names like oxytocin, which is the cuddle hormone. It is very important to me that my work is emotional, honest, and comes from the heart. I like to think of it like I’m trying to map out the far corners of my inner consciousness. There is a lot of ground to cover, and I don’t know how much time I have, so with every new painting that I create I have to explore new territory and challenge myself to do something I don’t know how to do. It is a game I have with myself that I am trying to push myself into the unknown, and through this process I grow closer to the person that I want to become.

From what I understand about John Audubon, he was obsessed with drawing specimens as they live in nature. He’d scour the country looking for rare or elusive birds in their natural habitats while other artists were content to draw stuffed ones. While these scenes clearly aren’t from nature, it seems as though there’s a similar importance on context. What do these environments represent for you?

I think there are a lot of artists that would love to have the opportunity to do their research out in the field, but it isn’t always easy to do. Audubon worked hard to study his subjects at a time before binoculars, so he had to resort to killing some of his specimens to see the detail up close. You can see this in some of the unnatural poses of his subjects.

Artistically I think like him, I share his admiration for nature and technical craftsmanship, but our goals are very different. Audubon set out to describe the birds and mammals in Northern America before they vanished. I do not have a scientific goal in mind to describe living creatures in their natural habitat. I do my homework and research animal behavior in the field as well, but only to help me understand the similarities that I have to other creatures. In other words, I arrange organisms that may never normally appear in nature together to help me understand my emotions and my relationship to nature.

How do you come up with the images you paint? Do you look at a lot of specimens?

I have a huge appetite for learning as much as I can, so most of the time spent out of my studio I am traveling overseas or hiking around California. I take a lot of photos in my trips and reference some of the photos that call out to me. Sometimes I bring interesting leaves, flowers, and icky bits to my studio and pose them to create settings. Sometimes I bring several photos together, or I build sets or dioramas in my studio. Every painting is the result of playing around, trying new things, and each is different from the next.

These paintings (or several of them, at least) were done on maple panel. Why did you choose that material?

I have tried painting on many different varieties of woods over the years, and I finally settled on maple. For many years I have been working with Francisco Robles, a custom woodworker based in San Francisco. Together we developed a system that seems to give the greatest results. Francisco first starts out by bleaching each panel of wood three times before I lay any paint down on it. I paint thin diluted washes of acrylic and the grain shows through the surface. By painting on the whitest wood possible I have better control of color and contrast. Maple wood also works well because it has a very tight, even grain, so when I’m painting the pigment onto the surface of the wood the color doesn’t bleed off into the cracks.

What’s it like as a painter to work with scientists?

I gravitate towards individuals who are fascinated with the natural world and feel compelled to use their imagination to discover and create new things. Both scientists and artists are creative and develop unique specialized skills that hopefully benefit and educate our community. Many of the curators and staff at the California Academy of Science, where I do most of my research, have been extremely generous by sharing their incredible knowledge and resources with me.

I feel very privileged. I want to work as hard as I can to share all of the wonderful and beautiful things that I love in this world.