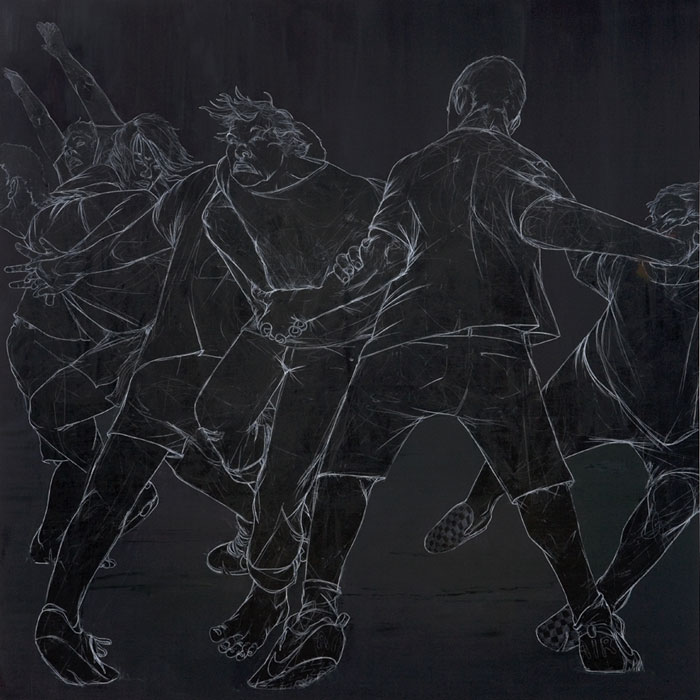

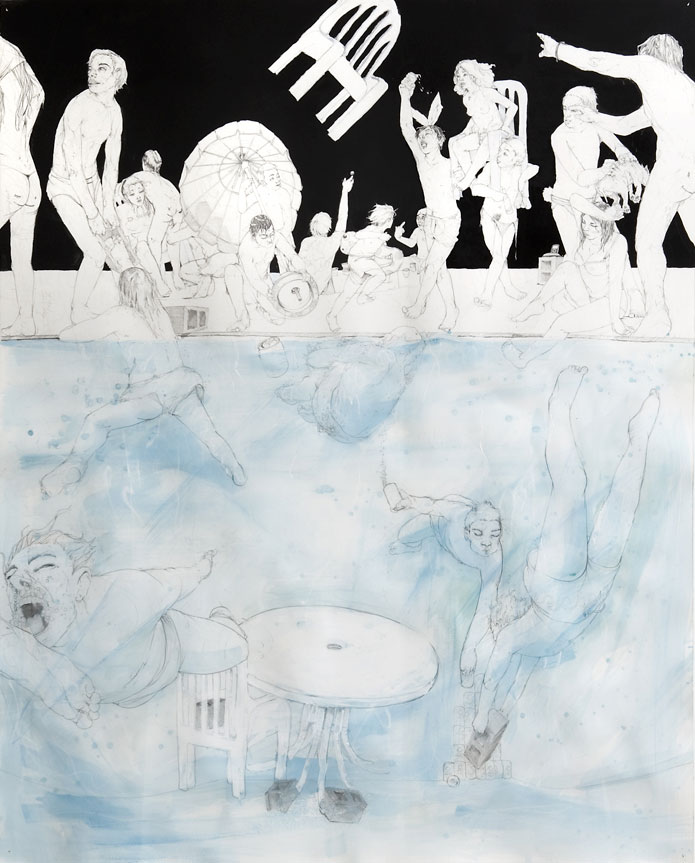

The impish, chaotic boys in Maximilian Toth’s paintings are Maurice Sendak’s Max, the neighborhood playground prince, and your nephew who pretends kitchen utensils are guns. These “little beasts,” painted to look like chalk on blackboard, represent the energy and spirit of childhood as it clashes with the order of the developed world.

Maximilian Toth, born 1978, received a BFA from Art Center, Pasadena, and an MFA from Yale in 2006. He has exhibited at Franklin Artworks, Minneapolis, Wadsworth Athenaeum, Dallas Contemporary, Daniel Weinberg Gallery, and Jack Tilton Gallery. Toth lives and works in New Haven. “Little Beasts,” on view this past December and January, constituted his second solo show with Fredericks & Freiser.

Why were you drawn to capture the destructive or wild energy of boys?

Because it’s something that I strongly identify with. Whatever the age, the moments of transition interest me. Those moments in which our accepted construct of morality no longer fits. Our physical or bestial side rears its head, unyoked we reach out to find the parameters of our new morality, and we engage, yet again, in making a new peace between our urges and our beliefs. We come of age.

Who are these “little beasts?”

The children in these paintings are not any particular children. The stories are inspired by the things my siblings and friends and I grew up doing. But they become the subject of a piece when they have both a compositional and a narrative depth and interest.

Is this a sort of “every” childhood?

I work from what I know. I think that the more specific the narrative, the more accessible it becomes.

You must have played these games—we all did, right? Are you or your experiences in here somewhere?

Definitely. Still do. My brother and I played four-square with a whole playground of little kids this summer. We destroyed them.

Is this all in good fun? Or are these scenes emotionally loaded?

I am not sure if those are separate things. At some point while visiting home for the holidays and catching up with close friends I had grown up with I realized that we had been telling the same stories for nearly 15 years. Everyone had certain narratives that stuck to them. They were almost always fun. But I think their importance was that they were moments that we had all learned something. Even if the stories were about a particular individual or silly they were our communal story.

How did you decide to use the “chalk-on-blackboard” effect in your work? It seems kind of appropriate both to the mystery and the nostalgia of the subject. The black chalkboard ground was created out of frustration at my own inability to articulate what I wanted through the work. I’ve always been interested in the depth of human experience exposed by moments of youth negotiating between the physical instinct of their bodies and the rules and expectations laid upon them. But in the beginning the work was smaller and easily passed over for angsty shallow boys gone wild.

When I looked at kids playing the pass-out game, I saw a biology lesson showing that the body is a machine: if you do this step, then that one, you can shut it off (not that you would want to). But it becomes less mystical. So what if it was drawn out like a scientific equation? What if this figure acts on that figure and yields this action? The equation—made figurative and narrative—needed the blackboard to support its reference. That’s how the first blackboard pieces were born.