In Above Paris: The Aerial Survey of Roger Henrard by Jean-Louis Cohen (Princeton Architectural Press, 2006), we see the polygonal French capital, between 1950 and 1972, as preserved from a single-engine army plane. Its pilot, Roger Henrard, was a businessman and an artist, and his bird’s-eye pictures of Paris, a city that can seem heavily barricaded and crammed together from the sidewalk, reveal the air pockets in its planning.

An excerpt from Cohen's introduction follows. Jean-Louis Cohen is an architect and professor of architectural history at the University of Paris and the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.

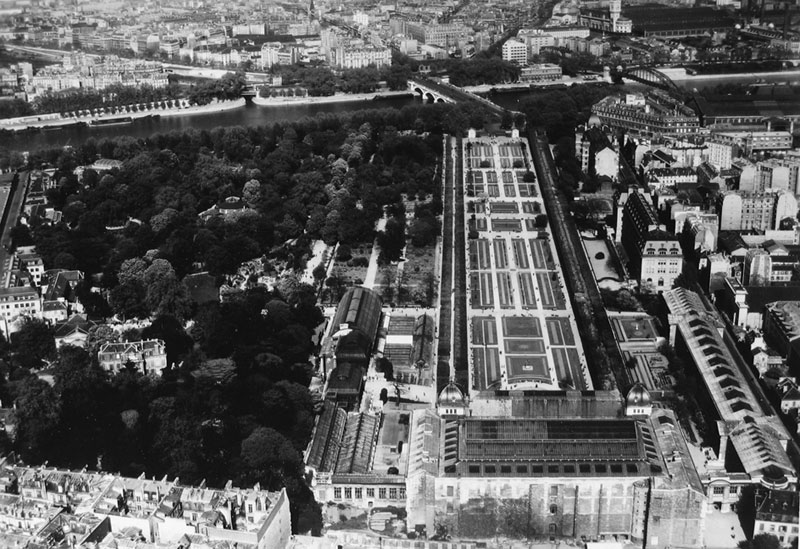

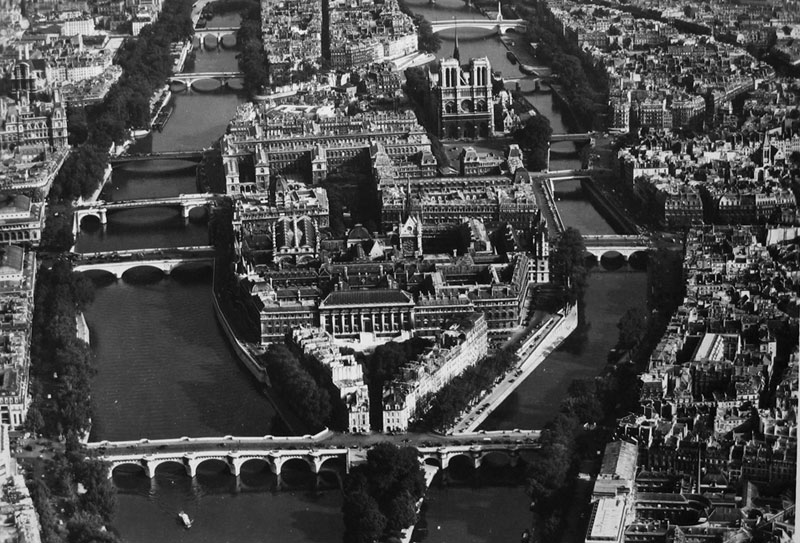

For over two decades, the sky above Paris played host to an extraordinary encounter between a man, an aircraft, and a city. The man—Roger Henrard—led a triple life as industrialist, pilot, and photographer. His book Un Enragé du Ciel (The Flying Madman) relates his exploits as a daredevil pilot during World War II and describes the circumstances that led him to explore the French capital from the sky. Henrard, who was born at the turn of the century, became director of a factory of photographic instruments in 1930 and developed an aerial camera, which he started to use himself after learning to pilot a plane. His first flying observatory was a high-winged single-engine aircraft designed in 1932—a Farman 402, with a 120-horsepower Lorraine engine. Henrard turned this plane into what he called a veritable “optical and mechanical laboratory,” using his own aerial camera system to take bird’s-eye shots of Paris. Thanks to a permanent flight permit from the Air Force, the self-dubbed “familiar bird” of the Parisian sky was able to devise a rigorous all-weather photography system.

In 1948, after his extraordinary wartime adventures as a reconnaissance pilot, Henrard resumed his flights over Paris at the controls of a Nord 1203 Norécrin (a low-winged aircraft derived from the Messerschmitt Bf 108), in which he installed the rapid cameras that he would continue to use for his aerial photography until 1972, three years prior to his death. In his preface to Un Enragé du Ciel, Henrard’s wartime squadron companion, novelist Jules Roy, describes how the photographer used his ingenious “mechanical retina”:

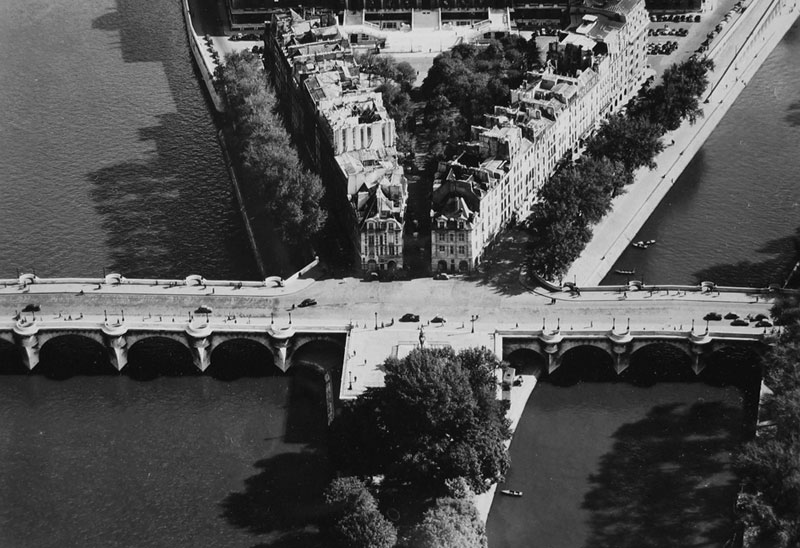

“In cramped conditions and with the sun at his back, he takes his photos with all the precision of a fighter pilot performing a snap roll or a bombardier landing his crate in a vineyard. He calculates itinerary and arrival time, always picking out some makeshift airfield on which to crash should his only engine fail. Over Paris, for example, he is more or less sure of always being able to make a crash landing—on the Seine between two bridges, on lettuce and spinach plants at Gennevilliers, on the Vincennes rifle range, or on the glass roof of Gare de l’Est. And why not on the terrace of the Galeries Lafayette?”

Last but not least in the three-way encounter is the Parisian metropolis, which still had a clear-cut outline in those days. When Henrard took the photographs in this book, the capital had not yet acquired the nebulous form of France’s major metropolitan area and was still a compact city, contained within the fortified wall built by Adolphe Thiers in 1845. Today’s metro maps and city guides still show its asymmetric polygonal form. A hundred years after the wall was erected, Henrard circled the city tirelessly, taking photographs by the thousand and producing a remarkable survey of an urban landscape in the throes of modernization.

Henrard was not the first photographer to capture Paris from a flying machine, but his approach differed from that of his predecessors, and his artistry contrasts with the cartographic dimension of government-commissioned reports. Bird’s-eye views of Paris existed prior to the aviation age, and Henrard’s photographs are links in a long chain—from prints that predate the age of the aerostation to today’s digital satellite photographs. This chain is really two-fold—one strand comprises views or panoramas taken from towers or steeples, the other consists of pictures from aerostats and flying machines of all kinds, from the latter half of the nineteenth century onward.

—Excerpted from Above Paris: The Aerial Survey of Roger Henrard by Jean Louis Cohen (Princeton Architectural Press, 2006)