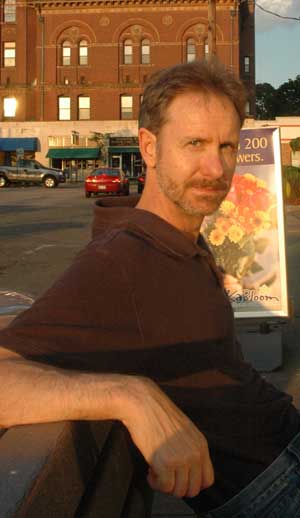

Writer Ron Rash has written three books of poetry—Eureka Mill, Among the Believers, and Raising the Dead—and two collections of short stories, The Night the New Jesus Fell to Earth and Casualties. He is also author of two novels, One Foot in Eden and Saints at the River, and one children’s book, The Shark’s Tooth. His writing has been published in Yale Review, Georgia Review, Oxford American, New England Review, Southern Review, Shenandoah and others. Rash’s awards include the Appalachian Writers Association’s Book of the Year and ForeWord Magazine’s Gold Medal for Best Literary Novel, both for his 2002 debut novel, One Foot in Eden. Ron Rash’s family has lived in the southern Appalachian Mountains since the 18th century, and the region is the primary focus of his writing. He grew up in Boiling Springs, N.C., and graduated from Gardner-Webb University and Clemson University. He is currently the Parris Distinguished Professor of Appalachian Studies at Western Carolina University.

In Saints at the River, the small South Carolina town of Tamassee becomes embroiled in a headline-grabbing controversy after a 12-year-old girl drowns in the Tamassee River and her body is trapped in its depths. Maggie Glenn, a 28-year-old newspaper photographer, has been sent back to her hometown to document the escalating standoff between the girl’s parents, who want to retrieve her body, and environmentalists convinced the rescue operation will damage the river and set a dangerous precedent. Maggie, who left the town 10 years earlier and has done her best to avoid her father during that time, now finds herself revisiting her painful past. A budding romance with the reporter who accompanies her to cover the story is burdened by his own troubled history.

As Ron Rash reveals in the chat below, this story exhibits two of his primary concerns: children and the environment. Additionally and not surprisingly, we talk about southern writing and a host of connected and unconnected issues. It is a great pleasure to present this wonderful writer whom I discovered the old-fashioned way—serendipitously.

All photos copyright © Robert Birnbaum

Robert Birnbaum: Do you get above the Mason-Dixon line often?

Ron Rash: No. Not a lot.

RB: How many times in the last year?

RR: I’d say three. About a week, total.

RB: How does it feel? Do you feel it?

RR: Oh, yeah. I can tell the difference. In large part because of the way people react to the way I talk. [chuckles] One thing that’s been really exciting for me is having readers outside the South. That’s what we all hope as writers, that our work transcends the region. If it’s significant at all, it has to.

RB: You have been at this for a while, so perhaps you might have noticed whether mainstream America has shifted its way of accepting southern writing.

RR: In a sense, as a southern writer you are almost always fighting certain stereotypes. There are certain expectations of a southern novel. There’s going to be a crazy aunt in the attic and probably a couple of bodies in the basement, and you always have these kind of bizarre characters. But at the same time, a lot of that’s true. [laughs] One thing I am pretty much convinced of is that we are all kind of crazy in the world—some groups hide it better than others, maybe. Southerners seem to revel in their oddness at times.

RB: Southerners do seem to be good at telling those stories about their oddities.

RR: That is something that is positive—that people expect southerners to tell stories, and southerners are good at that. It’s part of our culture.

RB: As opposed to midwesterners? Or westerners?

RR: Well, why is it that the South has produced so few philosophers yet so many novelists? There is something—we express ourselves with story. Once again, it’s not like every other culture doesn’t. A number of my favorite writers—I love Philip Roth’s work. He comes from a culture that’s probably the antithesis of a southern culture, at least within the United States. I grew up hearing stories, and it was a very natural part of my life.

RB: Years ago when I spoke to Reynolds Price, I was operating under the bias that southern writers were being marginalized, that the writing was quaint but not universal. So what I am trying to get at is whether there has been a change in the stature of southern writing.

RR: Yeah. Right now, as compared to the ‘30s and ‘40s, when you had an emphasis on people like O’Connor and in the ‘50s, Welty, Warren, and Faulkner, right now I find it interesting, that at least nationally, when I read the New York Times Book Review, how few southern writers are recognized as being among the greatest. I think Cormac McCarthy, Barry Hannah, William Gay are writing as well as anybody in this country and yet you hear about McCarthy but you rarely—

RB: You consider McCarthy to be a southern writer?

RR: Yeah he grew up in—

RB: I know where he grew up, but you still consider him a Southern writer? [He grew up in Knoxville, Tenn.—eds.]

RR: Oh, yeah, we claim him. [laughs]

RB: This regionalizing just seems to point to Jim Harrison’s notion of geographical fascism [mentioned in the “Tracking”section of The Summer I Didn’t Die]—suggesting some stratum of quality.

RR: I agree. Ultimately McCarthy and Hannah and Gay are great writers, and I have always been a little leery of any adjective in front of writer—whether it’s Jewish writer or southern writer. Because very often there is a sense of “just.” “Just a southern writer.”

RB: Not exactly a compliment or a superlative.

RR: And also not getting at what matters. If the writer—if McCarthy doesn’t transcend the South or Barry Hannah, they are probably not that significant anyway. I think they do.

RB: It does seem that southern readers are extremely loyal and supportive of their writers.

RR: Well, yeah, southerners like to read southern writers—it’s just that tradition since Faulkner and O’Connor—there’s regional pride in our writers and support of them. That’s a wonderful thing.

RB: Is the South still the same?

RR: No. It’s always changing. At the same time, what I find interesting is how it seems to both change and not change. Just when you think there’s no such thing as a distinctive southern culture, I see something that says it will always be like this.

RB: Was One Foot in Eden considered a so-called breakout book for you?

RR: Yeah, it did, it did, more so than any books I have written.

RB: You’re including your poetry?

RR: I’ve written three books of poetry and two books of short stories, but today novels just have much higher visibility than poetry.

RB: It is a pleasant surprise that short story collections seem to keep being pumped out.

RR: Well, what happened with One Foot in Eden was that it sold much, much more than anything I had ever written, and it got reviewed in places I had never been reviewed.

RB: Why do you think?

RR: Novels—more people buy novels and they just seem to get more attention than a book of poems.

RB: But why you, now, a writer from South Carolina? What were the reviews like?

RR: They were very positive—at least the ones I saw. Probably the best one I got was in the Los Angeles Times. To me that was a good sign that as “regional” as the book was, ultimately there was something in it that transcended the region.

RB: I liked the opening of Saints at the River, which I had picked up unaware of anything about you and never got further into it until we arranged to talk but I did for some inexplicable reason read One Foot In Eden and was mightily impressed with it. It was an enthralling book. When I came back to Saints at the River, the protagonist, the woman photographer, didn’t convince me. The prose was fine and fluid and the story was interesting, but it didn’t move me in the way your first novel did. What do you think? Do you look at all your children in the same way?

RR: Well, that’s just it. You’re being asked to choose your children—which one’s your favorite. [pauses] To me, if I had to choose between those books, I would choose One Foot in Eden myself. Part of it is because it was the first novel I had ever written. I don’t know—I have some readers who like Saints better. I guess it depends on what you are looking for. For me the language is more interesting in One Foot—which is something that’s important to me as a poet.

RB: I loved that story that is included in some of the biographical notes about your grandfather reading stories to you except he couldn’t read so he made them up.

RR: Oh yeah, it had an impact on me.

RB: Did you learn that much later?

RR: I figured it out pretty early. Probably in third or fourth grade. At the time it was just wonderful [laughs] that his stories could just change.

RB: Is the picture of folks sitting around telling stories and, in a sense competing, an accurate one?

RR: Oh, yeah, I did grow up with a lot of people who told stories. One thing I think was advantageous to me, two things. One, I had a speech impediment when I was four or five years old. And I didn’t talk much. The other thing is I spent a lot of my time in the summers with my grandmother, just she and I on a farm up in the mountains of North Carolina. And I would be around my older relatives and there was no TV—we didn’t even have a car on the farm—so we were just marooned there, in a good way. I would just listen to these stories and listen to the way these people talked. That was a great thing for somebody who wants to become a writer. I didn’t know I was going to become a writer then.

RB: When did you know?

RR: It’s a strange thing. I always loved to read. When I was in high school and college I was mainly an athlete. I ran track—800 meters. But the kind of obsessiveness I had in running and all that kind of stuff led into literature and the love of reading. But I didn’t start writing seriously until my late 20s.

RB: What did you do?

RR: A lot of it was running track, and reading and going to school. I have a straight M.A. in English.

RB: Is there a big difference between South Carolina and North Carolina?

RR: In some ways. I live in Western South Carolina and grew up in Western North Carolina and they are very much the same

RB: Asheville in the western North Carolina. What is in western South Carolina?

RR: Not much. Clemson University and Williamston, which is the best-known city.

RB: Most of what I know of South Carolina comes from Fox Butterfield’s book All God’s Children, which was about a African-American teenage murderer whose family was from South Carolina. In the book, Butterfield gives a brief synopsis of the state’s history and it seemed to be a tough, mean-spirited, martial, hard-scrabble place. And I only know of two writers from there—Dorothy Allison and Percival Everett—and neither stayed there. Is the impression I got from the book at all true? Is North Carolina looked at as more congenial?

RR: Not within the South. South Carolina has that strong sense of manners and those kinds of things.

RB: I always saw a certain kind of courtliness as being very much a southern thing.

RR: Yeah. Particularly when you think of Charleston. But I’m on the exact opposite end of that. I am in the mountains, and it’s a different culture—

RB: Is there that east-west/liberal-conservative split?

RR: Around Chapel Hill they’re more liberal than the rest of the state, but for the most part it’s pretty conservative,

RB: I think I read in the indefatigable Dan Wickett’s interview with you that you don’t know when you start to write what form you are working in—so what determines whether it ends up a short story, novel, poem?

RR: I usually start off with an image—an image that essentially I obsess over. That I can’t get out of my head. One Foot in Eden, it started with an image of a young farmer standing in his field. Saints started with an image of a child looking up through water. The new novel that is coming out in April starts out with a trout in water. They start with images and I just follow them. Sometimes I have a vague sense of the story already, but mainly it’s just following the images.

RB: Do you still write stories and poems?

RR: Oh yeah.

RB: So it is still a real possibility that when you start what you write could be anything?

RR: One Foot in Eden started as a poem and then a short story and then a novel. And Saints did that. And this new novel was a short story that won an O. Henry and now is part of this novel.

RB: What section?

RR: The opening. I added a good bit but the first chapter is essentially the story

RB: What’s the world or community of literature like in the South? Is there congenial camaraderie?

RR: There is a sense of camaraderie. Very often, a lot of us don’t live close together but we keep in touch and there is a strong sense of camaraderie and also a real sense of an older generation helping the younger writers. I find that to be a very wonderful thing. Robert Morgan and Lee Smith both have been very kind to me and supportive, particularly a few years ago, and there is a real sense of trying to help each other out.

RB: Oxford, Miss., has a book festival; Sonny Brewer has something in Fairhope, Ala.; and there is an annual convocation in Nashville. I assume you go to some of these, but what happens when you go outside the South?

I taught classes for welders, and that was good because one thing I don’t like is the novel about the middle-aged academic who has a nervous breakdown—to me that’s tedious and when you are in that kind of rarified air, sometimes, it can be a problem.

RR: I did the Chicago Tribune and Printers row; I have gone on tour out West, and those are great. The fun thing for me is that when I go to ones like in Nashville and Oxford, I get to see friends. This is where southern writers will get together—we’re spread out. It’s not like Boston, where you have 50 writers within two miles of each other.

RB: I think of North Carolina and Vermont and Boston, Cambridge, as really densely populated with writers.

RR: Oxford, Miss., is really close. There are some good writers in that town.

RB: Who is there?

RR: Barry Hannah. Tom Franklin.

RB: The ghost of Larry Brown.

RR: The ghosts of Welty and Faulkner.

RB: Are there black Southern writers?

RR: Oh yeah. Percival Everett. I love his work. Ernest Gaines, Alice Walker. Let’s see, let me think. Marilyn Nelson.

RB: A.J. Verdelle?

RR: I don’t know her. Dori Sanders, from South Carolina, wrote a book called Clover that did well. Yusef Komunyakaa, the poet, grew up in Mississippi. Edward Jones—

RB: Considered a southern writer? He grew up in D.C. and went to school in Worcester, Mass.

RR: In his first book of stories, I got the sense that his family is very southern.

RB: Do you think that when people think of southern writers they include blacks?

RR: I do. Instantly I think of Ernest Gaines, who is very southern to me.

RB: Is there a state that is underrepresented in southern writing?

RR: In the South?

RB: Yeah, do people write about Kentucky besides Barbara Kingsolver?

RR: Wendell Berry. Silas House, a good young writer. Some states seem to do more than others. North Carolina and Mississippi are the two, you turn over a rock and—

RB: Probably it’s the water. Lee Smith has a significant body of work and is always mentioned by other southern writers, and yet her visibility nationally is very low.

RR: I don’t understand that. That disturbs me, that someone like Lee Smith or Barry Hannah doesn’t get his or her due nationally. They’re good enough. They’re major writers.

RB: Why don’t they?

RR: When I see something like what happened with the [2004] National Book Awards, where you had five finalists, all were from New York City—there’s a provincialism there. That’s pretty hard to deny.

RB: The worst part of that was the writers were being held responsible for it—

RR: No, it’s not their fault.

RB: It still seems to me that none of the women were really New York writers—they just happened to live in New York—their subject matter wasn’t New York-centric. So why not nominate them?

RR: I thought there were better books that should have been considered.

RB: That’s a whole other issue. That’s the inherent problem in awards—whittling down a list of 400 books to five and then to one. What were some of the books that you thought were better?

RR: There was a great novel that got no attention by Donald Harington, called With. And it’s marvelous.

RB: He’s written a bunch of books and he never gets attention.

RR: When I read it, I thought, “This book cannot miss.”

RB: The title is too simple. Who wants to read a book with such a simple title? [both laugh] Was it your intention to teach after you got your master’s degree?

RR: I was writing by then, but yeah, I had to get a job and I didn’t have a trust fund, so I spent a good part of my 20s trying not to write.

RB: Because?

RR: Getting serious and growing up. But as I got into my late 20s I felt, “If I don’t give it a shot, a serious shot, I will always be haunted by ‘What could I have done?’”

RB: Was there family pressure to “get serious”?

RR: No that was me. I’m sure it’s part of my culture that I should be responsible and get a job. I just felt like it was right.

RB: Tell me about your students.

RR: I taught two years of high school at a very small rural high school right in the South Carolina mountains, near where One Foot in Eden is set, as a matter of fact. And then I taught at a technical college for 17 years. And that was a good thing. A lot of my students were lower middle class, middle class first generation [to go to college]. I taught classes for welders, and that was good because one thing I don’t like is the novel about the middle-aged academic who has a nervous breakdown—to me that’s tedious and when you are in that kind of rarified air, sometimes, it can be a problem.

RB: Teaching English meant teaching grammar and such or literature?

RR: I taught it all. I was teaching five or six classes at the technical school—freshman composition, British literature, and I did teach surveys in that. Which I loved doing.

RB: Starting with Beowulf?

RR: Beowulf to Milton and then Milton to contemporary.

RB: And who were your contemporary choices?

RR: Seamus Heaney, Geoffrey Hill—as far as poets, Derek Walcott. I didn’t go much farther up then people like Graham Greene.

RB: What is life like where you live?

RR: I spend half the week at Clemson and half the week in North Carolina. It’s very rural. Probably very slow paced, at least to most people who are not from the region. Very pleasant. It’s a great place to live.

RB: Circling back to where we began, do you notice anything here in contrast to life where you live?

RR: One thing I noticed that is very positive that I get from walking around is the sense of history.

RB: I had in mind my own experience in Boston, now that I live in New Hampshire. I noticed quickly that you rarely hear a car horn. And they have a respect for pedestrians, [laughs] when you are in a car and someone is crossing the street, you, as a matter of course, let them do it.

RR: I don’t spend much time in cities, but I do notice the pace. I have always lived in rural areas.

RB: But you use a computer and have ATMs which I am convinced are accelerants in their own right. You see people waiting in ATM lines, and they are super fidgety.

RR: When I see people like that I am reminded of Chaucer’s quote in Canterbury Tales, “Though there was nowhere one so busy as he, he was less busy than he seemed to be.” That’s true of a lot of people I see today.

RB: What are the problems or issues that occupy you? Imperatives or values that you want to write about, or is it just as you said, an image comes up and you respond?

RR: One thing I think has been clear in my work that I didn’t realize consciously, really, until Saints at the River, is that I am very preoccupied with children. And I am sure that’s because I have children, the kind of fear that parents have that something can happen. I never really noticed it but looking back at my work I see it again and again. And I am certainly concerned with environmental issues, but at the same time you have to be very careful because if you are didactic that can kill a novel.

RB: There are novels that deal with really bad things happening to kids. I start them but usually can’t go far. Stephen Dixon’s Interstate comes to mind and John Burnham Schwartz’s Reservation Road.

RR: Russell Banks’s The Sweet Hereafter, which is one of those grim ones—

RB: Siri Hustvedt’s What I Loved is very much like that—I was reading it and in the middle this thing happens and I am on the verge of tears. I wonder how one can write that kind of situation. To me, that’s grimmest possible thing to write about.

RR: In a way, it can be almost cathartic in the sense that you are almost confronting your worst fears. Also, if I make it up and put it in a story, it can’t come true. There is almost that kind of feeling about it.

RB: In Saints, early on you are clear that a young girl is a goner and you accept it—it seems not to be as harrowing as if it came later.

RR: Yeah, that’s right.

RB: Is where you live at risk from industrial assault?

I went to schools that were completely integrated and you may have this view of the South as being a very segregated culture; even today I have friends who come from other regions and their schools were very segregated. But the schools I went to and my children went to are completely integrated.

RR: We have to worry about that more than anything, particularly in the mountains because so many people are moving there—

RB: Really?

RR: Particularly North Carolina mountains—retirement communities are springing up. A lot of the rivers and streams are being polluted and just so much pressure because of more building.

RB: What about environmental protection agencies and groups?

RR: There are but it’s private land and particularly the Chattooga River, which I care a lot about. There has been a lot of building near it, and what happens is the sediment will get into the river and it really has an effect.

RB: What happens?

RR: Kills the trout and fish populations. A beautiful river becomes less pristine and ultimately destroyed.

RB: What’s the local response?

RR: There’s a real movement toward conserving these rivers. There are several groups, and on some level I’m involved with these groups that are trying to protect these rivers and protect these streams.

RB: Are rural southerners joiners? I’d guess not.

RR: That’s probably true.

RB: So is environmental protection a cause for which people would overcome their hesitation to join groups?

RR: They have, at least where I live. It’s a minority but I have two friends who have dedicated their lives to protecting this river. They are barely scraping by economically but they love this river so much that they are doing everything they can.

RB: I imagine it’s less expensive to live in your neck of the woods.

RR: Oh yeah.

RB: So when you say “barely scraping by,” how low is their life style?

RR: I don’t know exactly but I would guess $15,000 a year.

RB: What is the work? There’s still farming?

RR: Still agriculture. Some manufacturing. Tourism is really big.

RB: That would cut both ways. As exhibited in Saints at the River, good for local economies and burden on the environment. Any of that land protected as parkland?

RR: The Chatuga is actually a “wild and scenic river,” which means it’s protected and there’s a certain buffer zone and all of that. And there is a lot of national parkland and where I teach is only 30 miles from the Smokey Mountains National Park.

RB: Your position at Western Carolina University is distinguished professor of Appalachian studies. What does that involve?

RR: It’s a study of that culture—the music, the geology, and history and literature and an emphasis on that particular culture.

RB: Are there many departments like that in the South?

RR: No.

RB: Would that be the only one?

RR: It might be. One good thing for me—I mean, there are many things but one thing in particular, and it is especially true for my younger students: A lot of them come from there and there are all these popular culture negative stereotypes about Appalachian people—Deliverance, The Dukes of Hazzard, the hillbilly stereotype, and at the same time you don’t want to sentimentalize, but there are positive aspects of this culture as well.

RB: Your accent is not Southern. It is more what would seem to be Appalachian?

RR: It is.

RB: And you study the differences in dialect?

RR: There have been studies done.

RB: How does one describe the difference in accents?

RR: With particularly the more coastal accents in the South, more like Mississippi, it’s much softer.

RB: Can you talk like southern, imitate one? [laughs]

RR: Almost softer and whispering, maybe more nasal.

RB: Which part of your mouth do you use?

RR: Back, deep, more guttural. But it’s different. When you go from western South Carolina to Charleston, you will hear big differences as you go across the state.

RB: How integrated—are there black people in western South Carolina?

RR: Not as many as in Charleston, because there were no plantations. The land was not [used] that way. There are and were black people. I went to schools that were completely integrated and you may have this view of the South as being a very segregated culture; even today I have friends who come from other regions and their schools were very segregated. But the schools I went to and my children went to are completely integrated.

RB: When I talked to Reynolds Price, he observed that one distinctive part of southern culture was the great familiarity between blacks and whites. I grew up in Chicago, and there were no black people in the schools in neighborhood until the ‘70s, and Chicago was deeply segregated and still is. Is your view of your work as a career, as in “career arc”?

RR: I have never thought of it as that. I’ll be 52 in a month, and I have been writing seriously for about 25 years now, and most of that time I have been publishing in small journals and nothing really happened, no career, and I just do this because I love it.

RB: Do you pay attention to the attendant stuff, trade magazines. New York Times Book Review, book industry gossip?

RR: I’m human. It’s wonderful to know that my books are selling. I don’t want to obsess over it. And I also—the one thing I don’t want to happen is that I get so concerned with that that I get where I am not focusing on the writing. I am a writer and I don’t want to get to the point of whatever that other thing is—I just want to write.

RB: Well, you seem to have chosen a sensible path.

RR: I have a job now, so I don’t have to write. I do it because I want to.

RB: Do people actually graduate with MFAs expecting to make a living?

RR: I don’t think so. There may be a few, but the vast majority realize—

RB: The reality is too crushing. Why do you think there are these constant complaints that suggest otherwise—that somehow writers should, in the main, be supported?

RR: I don’t know. All you have to do is look around and see how many writers can make a living.

RB: Do you think literary fiction is at risk?

RR: There may never be a huge number of people who read it, just as with poetry, but it won’t disappear. The people who love serious literature and love poetry, they are going to care so much they won’t allow it.

RB: Yet it’s an ongoing debate. Civilization is always ending and literature is always disappearing.

RR: You go back and look at John Donne, who was passing his poems around at court to about 30 people—there was not much of a readership there, either.

RB: Yet in 19th-century, someone like Dickens was hugely read.

RR: It was popular entertainment in a sense that was Nintendo and TV and all that rolled into one. That was the primary source of entertainment. Now people have more alternatives. I would like to think—and I do—that there will continue to be people who want serious fiction. And what disturbs me is the rise of theory in universities and colleges. Which is anti-literature.

RB: All that passed me by. I was out of school by the time critical theory was the big thing. I have not read one book by Foucault, Derrida, and such. When I studied philosophy it was Wittgenstein and the ordinary language and logical positivist movements. When I talked with Camille Paglia recently she is vociferous in her disdain for the theory, which she blames for destroying academia and everything else.

RR: I like her writing a lot and what she has to say.

RB: A book is coming out next year. What have you been doing since you finished it?

RR: I have been writing some stories in the last couple of months. I had a backlog. I finished One Foot in Eden and started on Saints before I got One Foot in Eden published. These novels are all taking me two to three years but they were stockpiled; I’ll have another book of stories coming out in about a year and a half and they are already written.

RB: You write them serially but not with the idea that they will be in a book together?

RR: I just write them as they happen.

RB: Do you think of other kinds of writing that are more collaborative—librettos or screenplays?

RR: Probably not. I just wouldn’t have the confidence to do it. I have just never thought about it.

RB: Arliss Howard and Debra Winger did a wonderful job with making Larry Brown’s Big Bad Love into a film.

RR: It could happen. Russell Banks has been very fortunate in the way people have done his movies. They have done good treatments of his novels. So it can happen.

RB: Affliction was so powerful, and it seemed like an unlikely story to make.

RR: That’s the one I’m thinking of.

RB: I think he is still working on Book of Jamaica and Continental Drift.

RR: He’s a writer I admire.

RB: Why?

RR: He writes about tough issues to write about and in a truthful and honest way. He goes to the heart of things. And another writer I love a lot is Robert Stone—I like his ambitiousness. A book like A Flag for Sunrise, that is a big landscape novel. He and McCarthy are two of the most disturbing writers I know. I read those guys and they really shake me up.

RB: You can’t read a Robert Stone book without knowing that there will be people in trouble—

RR: And it’s only going to get worse. [both laugh] It starts off bad and gets worse.

RB: I picked up Blood Meridian again recently, and I thought the opening chapters were funny.

RR: The preacher, oh yeah.

RB: Any more writers like Donald Harington that you think are deserving of greater or, as in his case, some attention?

RR: I liked Saturday by Ian McEwan, and it got mixed reviews but I like its ambition. I read Harington’s The Pitcher Shower—I thought that was good. I go back and reread Dostoyevsky pretty regularly. In a way One Foot in Eden is my Crime and Punishment. That book had a huge impact on me when I was a teenager. I read it when I was about 15, and it has always stayed with me. Another book I recently reread was Percival Everett’s Erasure. That’s a funny book.

RB: It sure is. Why did you reread it?

RR: I had been thinking about it. I read it when it came out and I wanted to go back. One reason was because I wondered why the book didn’t get more attention.

RB: The perpetual question. I wonder about the complaints that so much crap is being published that fails to acknowledge that lots of wonderful writing is being published that readers miss.

RR: A good thing about the Internet is that these books will get attention that they might not get otherwise—someone like Donald Harington.

RB: My pick hit of the moment is Don Winslow’s The Power of the Dog.

RR: Don’t know it. [both laugh] That’s your point, right?

RB: I pointed it out to a few people who were equally impressed. And that’s a wonderful feeling. It’s the joyful part of all this.

RR: That’s right.