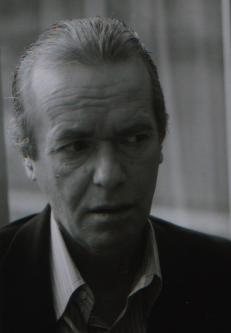

Although Martin Amis ought require no introduction—especially to anyone mildly familiar with contemporary literary fiction—it’s possible that among you there are those for whom his name draws a blank. He is the son of British novelist Kingsley Amis and a member of Granta’s first Best Young British Novelist list—which, back in 1983, included William Boyd, Kazuo Ishiguro, Salman Rushdie, Julian Barnes, Ian McEwan, Graham Swift, and A.N. Wilson. Amis has written 11 novels, as well as a number of short story and essay collections. His personal life has been regularly invaded by British tabloids earning him the rubric, “the Mick Jagger of British literature” (though I am more inclined to refer to Jagger as the Amis of British pop music).

I am pleased to point out that this my fifth colloquoy with Martin since 1992, and this one was occasioned by the recent publication of his new novel House of Meetings, which he refers to below as his most challenging bit of writing. We variously talk of Uruguay, returning to London, raising children, Saul Bellow, growing old, and a few other matters. I don’t think it overly optimistic to offer Part Six of Martin and me in the not-to-distant future. I would hope you stay tuned…

Robert Birnbaum: How are you?

Martin Amis: Fine.

RB: Really?

MA: Yeah.

RB: This is a good period in your life?

MA: We have been away. We have been in Uruguay for two and a half years—having gone down for successive Christmases, which is high summer there. My wife is half-Uruguayan and she has 25 cousins in Uruguay. Twenty-five first cousins. And we lived there for two and a half years. The girls went to school and learned Spanish in about a week.

RB: You didn’t?

MA: No.

RB: You need a reason—

MA: Well, yeah—someone comes to the door and babbles at you and you shout, “Cleo!” and this five-year-old comes down and listens and explains, “He wants you to open the back gate so he can get his truck.” [laughs] The schools down there are awfully cute. The lady teachers kiss them [the students] good morning and goodbye every day. All of the teachers kiss all of the children.

RB: Not a Catholic school?

MA: No, Uruguayan. They are lovely people. They really are. Incredibly nice people. The school was nice and cute but it wasn’t a serious school. So it was either New York or London. And the fact I had three other children in London swung it that way. So we are back in London. We actually had a terrible period of builders in our small flat. And that is demoralizing beyond belief. But they are gone and things are fine.

RB: You are adjusted to being back in London, such as it is?

MA: Yeah, I’ve lived in London so long—40 years.

RB: I should remind you when we spoke last time, for Yellow Dog, you were disenchanted with London and thrilled to be going to Uruguay.

MA: Yeah, was I? Yeah, I did welcome that, being away from England. It’s not been at all bad getting back into it. Changed a lot, London has.

RB: Because of world terrorism? Economic conditions?

MA: Very multiracial. Even more so; we are in that kind of neighborhood.

RB: Asylum-seekers? People who are accepted as part of the society?

MA: A huge mix. A lot of EB’s as they call them—Eastern Bloc. I like that—I like intense variety; that’s good.

RB: They smoke incessantly.

MA: That’s true. London is very expensive. Cynically expensive. Fantastically and cynically expensive. It also shows that politically you can move—you can travel quite a distance across the floor, while staying in the same place.

RB: [laughs]

MA: Because the left—the center has moved. I wouldn’t insult the left by saying the left [is at fault], but it moved to a sort of woozy, complete terror of making any judgment.

RB: Unlike what had happened in the United States?

MA: It’s worse in England. I can easily tell you to what extent. I went on a TV show where you interact with the audience. Question Time, it’s called. And I was propounding what was the boringly centrist view that we should have finished the job in Afghanistan. And not got lost in Iraq. And we should have been tearing up the earth to find Osama bin Laden. Finish him. And they were all looking at me with incredulity, in the audience. And then a woman stood up, her voice quavering with self-righteousness, near tearful self-righteousness, and said, “Since America was the main backer of Osama while he was fighting the Russians, when Sept. 11 happened—in response to that—America should be dropping bombs on themselves.” And the audience applauded.

RB: No Jerry Springer antics?

MA: Jerry Springer is like a Nuremberg rally; this was a rally on the left, so-called. Very anti-American and anti-Semitic.

RB: And this represents what about England?

MA: That’s what we call the “right on” opinion. The Guardian-reading, capitulationist, defeatist—as if the West is incapable of being right about anything.

RB: And they stand where on the European Union?

MA: That’s such a marginal issue.

RB: The euro has not been the currency of England?

MA: No. [in a weepy, whiny voice] Not the pound sterling, mate; they are never going to take that away.

RB: I negotiated a fee to be paid in euros and ended up being paid in Irish pounds.

Nothing is happening in British politics. It’s a market state—it’s what is called a “golden straitjacket”—you don’t actually have much room for politics if you are a globalized market state.

MA: How much are they worth? Quite a lot, I imagine.

RB: Equivalent to the euro.

MA: Ireland is a rich country now. Another other thing about coming back is that there are tons of newsprint. You have to bench-press the Saturday [London] Times off its shelf at the newsagent’s. There’s many, many of these broadsheets and a lot of it of very high standards by intelligent people, writing well on all sorts of things. But Iraq is interesting, Afghanistan is interesting, the war on terror is interesting, but a lot of it is about British politics. You just can’t believe—nothing is happening in British politics. It’s a market state—it’s what is called a “golden straitjacket”—you don’t actually have much room for politics if you are a globalized market state. You can’t upset the apple cart.

RB: So the political news is focused on the [prime minister’s] succession?

MA: That’s right. Things all about [candidate] David Cameron’s hairstyle.

RB: It is a good sign that there are lots of newspapers, yes?

MA: They are all in decline in England, not losing money but shrinking. It’s the internet.

RB: So here you are, talking about your nth novel. How do you view your readers? What responsibility do you assign your readers? I intended to say nth and think we should keep it that way

MA: In what sense?

RB: For example, in the last footnote in the book, around page 176 or so, I didn’t understand it. You mention the Stalinist inner circle, which I am familiar with, and then there is a reference to O’Hare airport. What did I miss?

MA: Did you read it in the proper-bound proof?

RB: I read the finished edition.

MA: Those footnotes are by [the narrator’s stepdaughter] Venus.

RB: They are?

MA: Yeah, it’s pretty clear. Remember the first one, she says—

RB: I missed that.

MA: The first footnote is about Josef Vissarionovich and says that he’s Stalin. And then she said, “It would have cost him his soul, I know, to type out the word Stalin.” The thing is she had the book printed. So she is doing the editing and explaining these things. Go and look at the first footnote and you will see that it’s clearly her. Although I bet you didn’t get this—she’s black.

RB: No, I didn’t. I never made that connection.

MA: It seemed to me that I didn’t need to say it. There were so many remarks. He says, “You know what it was like to be a slave.” And the mother was a sharecropper early in her life and he says, “You and your flesh have worn the star.” But that kind of deductive reader is gone. The reader now thinks that if she’s black he would have told me so. So it might have occurred to you but then thought, “He would have told me.”

RB: I don’t think that. My experience reading you, I don’t think that. That’s why I asked. I frequently find myself thinking, “Wow, what a turn of a phrase,” and so now I am outside the story. So I wonder how much you want me to stay in the story and how much you want me to acknowledge and applaud your skill and such?

MA: Yeah, well, yeah, you want to be read slowly. The thing is, sometimes a story is more propulsive and more involving than you think. And it does move along. And you really want to know what happened in that “house of meetings” and what’s going to happen to all three of them [the two brothers and the one brother’s wife], really. So that takes you forward and the prose slows you down.

RB: “Cloacal frenzy.” What a phrase! [laughs]

MA: Oh yeah. [pause] So there has always been a bit of unease about moving forward and lingering.

RB: You’re now in mid-career or something like that—what is the weight of your past work as you begin a new one?

MA: You get less and less interested in what you have done. And more and more interested in what you are going to do. And even reading proofs—

RB: Feels like work—

MA: I’ve done all that. I’ve done that book, and it’s purely a function, I’m sure of a diminishing future.

RB: [laughs]

MA: It must be.

RB: We could be of the generation that exponentially outlives our genetic heritage?

MA: We could.

RB: My father is 85, my mother 79.

MA: Yeah and we have this new phenomenon, not quite new—but it struck me recently—the octogenarian novel. Norman Mailer and Saul Bellow, I’m sure there haven’t been many of them.

RB: I was amused to read recently an essay by Joseph Epstein called “The Kid Turns 70,” written upon the occasion of his latest birthday. He suggested at certain age it was prudent to think in ten-year increments of life expectancy.

MA: Yeah, you take it one decade at a time at the most. Or one year at a time. And it’s all unknown territory, isn’t it? Your 50s are unknown territory. Your 60s are going to be unknown. It’s all unknown right from the start, really. So you are a child all your life.

RB: [laughs] But we have people telling us—

MA:—That’s no good. You can read every novel ever written and it won’t prepare you for it. Because it’s not new.

RB: So what’s the value of it? Amusement? [laughs]

MA: Variety of feeling, or something. It’s not just mapping out the territory ahead of you.

RB: God forbid people should read novels for advice. Or maybe it’s about commiseration?

MA: We talk a lot—my contemporaries about this. We all agree that every time you look in the mirror we must be on acid or something. It’s sort of a trip—

RB: No longer young Turks.

MA: That’s for sure.

RB: But not old Turks either.

MA: Not quite yet, no.

RB: I wonder if by sheer number we now get to define these generational fault lines? That tired descriptor, “baby boomers,” is creating some novelty.

MA: And they are creating unprecedented economic troubles in the world, too.

RB: In the U.S. I read that the fastest growing demographic entering the job market are 55- to-70-year-olds. No doubt due to the great crimes of Enron and other corporations stealing people’s retirement funds

It’s all unknown territory, isn’t it? Your 50s are unknown territory. Your 60s are going to be unknown. It’s all unknown right from the start, really. So you are a child all your life.

MA: Back down the coal mine at 70.

RB: Not to mention there are people who are still competent and enjoy work activity.

MA: The world is too active and mercurial—the idea of just smelling the roses for the last bit is gone. You are addicted to events. You want to be part of it. Not to one side of it.

RB: So—why did you want to write this book on the Soviet Union?

MA: It all starts—a novel starts with what Nabokov calls a throb. You think, “There is something for me there. That idea.”

RB: This idea came after Korba? [Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million—eds.]

MA: Well after.

RB: Did you think you were finished with Russia as a subject?

MA: Yeah and then I read Anne Applebaum’s book Gulag—she has these three pages on the “house of meetings” and I got such an astounding idea—think of having conjugal visits in Auschwitz. And the sort of hangover from the progressivist Bolshevik ideas about social hygiene being terrifically grown-up. And I was moved by that, so you get your throb, and then as Updike says, you are immediately surrounded by innumerable points of resistance that you have to work around. So I—I thought it was a short story when I started. And then it grew and I found I had to flesh it out for plausibility, and when I finished it I still thought it was a novella. When I saw it in proof, I thought, “This isn’t a novella, it’s a novel.” And I had a very great struggle with it, the most violent struggle I have ever had in my life, with a book. And that was really a fight for legitimacy, to write about a victim.

RB: Your first go with a new publisher, Knopf—anything to report there?

MA: I didn’t feel issues or anything—I mean it’s still the same publisher in England—so I didn’t feel as if I was auditioning.

RB: I wasn’t thinking that, but rather some period of adjustment in dealing with new editors and pre-publication matters.

MA: Oh, right. No, it’s been a long time since I took editorial advice. Although I should have done [something] about not being clear enough that she [Venus] is black. That’s important, and in the paperback I think I’d better use the N-word in a sentence, “Dear Nigger,” [laughs] “Dear Venus, nigger,” just to get people’s attention.

RB: Are you short on attention these days?

MA: No, no, just to get that across. In the paperback, it’s going say, “I don’t think you will excommunicate me from your affection or memory because you are black.” Spell it out.

RB: So when I go home I am going be querying myself on how I missed that.

MA: Robert, honestly, everyone missed it.

RB: Speaking of which—I am not a big reader of reviews but I do enjoy reading the ones you get. I am not clear on why you turned out to be controversial. But there it is. I was amused by Joan Acocella’s, however you say her name.

MA: A-co-chel-a.

RB: She loves you and she doesn’t love you. [laughs]

MA: Yeah.

RB: She gives you your props but she doesn’t want to give them unsullied by—

MA: Not with sugar on top.

RB: “Narcissism…on the other hand …” Is it that you have calmed down, that there are fewer flamboyant critiques? Are you viewed as graybeard now, to be respected? Nobody seems to be going after you as in the old days.

MA: Actually there was one. It was kind of nostalgic, really—I’ve stopped having those kind of reviews but it was one in the London Review of Books; it was quite late. It was a month late. And absolutely an interminable piece—5,000 words by a young guy who works at the London Review. That’s what it said—I looked in the contributers’ note.

RB: Was he paid by the word?

MA: I doubt if they are paid at all. But he was feeling his oats, naturally. And he’s read every word I have written. Obviously, spent hundreds of hours in my company—

RB: [laughs]

MA: And yet the little bastard said, “This is unpublishably poor,” this book. And I thought I used to get a lot of reviews like that by young guys who know my stuff backwards, probably better than I do, and say I am shit. Or this book is shit. And I thought, “Why do these little ingrates—why do I attract these little ingrates?”

Every novelist could write a really scathing review of each of his books; it’s not that they do that, but some shitty little phrase will get lodged in your head and you don’t want it in there.

RB: We can forgo the cheap psychologizing—why is a piece like that worth publishing? Because it’s important to take down the iconic authors?

MA: That was the only one like that. There were a couple of lukewarm ones, but I have had lots of those by people who know my work backwards. And then turn on you. No hint of a bit of gratitude for the hundreds of—no one was making them read me closely. They weren’t doing it for their health, were they? They were doing it because they liked it. And yet not a murmur of gratitude.

RB: Your last published short story attracted some buzz.

MA: The Muhammad Atta story [The Last Days of Muhammad Atta]? Yeah, a lot. Most of it favorable. It’s nicer being praised than being dispraised. I try not to read [reviews]—because you don’t want them in your head. The trouble is, and I really recognize this, is the novelistic ego. If you get praised you absorb it in an instant and it gets you up to where you should have been already.

RB: [laughs]

MA: But dispraise; it’s not that it strikes home and he nails you and gets your faults. Every novelist could write a really scathing review of each of his books; it’s not that they do that, but some shitty little phrase will get lodged in your head and you don’t want it in there. I know a couple of very well-known writers—I won’t say who they are—who find they have a funny little addiction for chasing down slander of themselves, on the internet. Spending two hours a day reading shitty things about themselves. Because I am the son of a writer it’s never struck me as being a huge deal, being a writer. Nothing is more banal than what your dad does, right? So I have quite good instincts about steering clear, not needing to read the reviews. You want the reviewer’s assurance that you haven’t gone insane in the past few years but once you’ve got that than you can stop reading.

RB: Are there bellwether reviewers who you pay attention to? You take seriously their commentary, you learn something from them—

MA: Oh, no—never, never that. There are some ones that you want to like you and it’s a bit of a facer if they don’t. But you are not going to get any instruction—James Wood, for instance, have you read him? I am interested in what he says.

RB: I am interested in Wood’s views—this despite divergent tastes. I don’t seem to like the books he likes. He’s smart.

MA: Yeah, he’s smart. And [he has] nice prose. And he notices and is attentive to prose.

RB: He shows a respect for the effort—no cheap shots.

MA: Yeah. He’s a good quoter. Although if Salman Rushdie were here he’d go purple and say, “He praised me when he wrote a 1,500-word piece about a book. But then he wrote a 5,000-word piece about me and said I’m shit.” He does have that habit—if he has a lot of space to cover you have to be very good for him to sustain his interest over 5,000 words, or whatever it is. But he is a good quoter and quotation is your only hard evidence as a critic.

RB: What seems not to be disputable about this book is the visceral, the saturation of the dystopian-and-beyond sense of the Soviet Union you create. Which makes me wonder if you are a disappointed utopian or an unrepentant dystopian? [both chuckle]

MA: Probably a bit of a dystopian. I am tremendously suspicious of the idea of utopia. It’s not going to happen. And in fact, it’s Plato’s or Aristotle’s Utopia—that first description of utopia—it’s really meant to be an analogy of the human mind, the well-ordered mind. Where you have a strong will—i.e. strong police—and it’s really a metaphor for a good head. A disciplined mind.

RB: Is that where you get the idea that countries and people are similar?

MA: No, not from that. It’s sort of an odd thought. I realized a friend of mind who died a few years ago—I found myself thinking he was a failed state [both laugh] and we all know a few failed states, don’t we?

RB: Speaking of which—far be it for me to chart out your future projects—I wondered why having spent time in South America didn’t surface in your work?

MA: You are never going to write about it in fiction when you are there. It’s got to sink in and get stirred up in your subconscious. There are scenes in the novel I am doing now that are set there. But it’s too sweet a place—there is not enough conflict in Uruguay.

RB: You missed by a quite a few years their fling with military dictatorship—what was their main prison named, Liberty or something?

MA: Yeah, La Libertad. No, it wasn’t as bad as elsewhere. But it was quite bad and among my wife’s cousins more than two or there had been tortured. And one had done 12 years for murdering a policeman. They were all 19 when this happened, and were [on the] left.

RB: The Tupamaros were Uruguay?

MA: Yeah.

RB: I think their credo was “Cada uno baila o nadie baila” [“Everyone dances or no one dances”]. They made the fatal mistake of kidnapping a Ford executive and accidentally killed him. That turned their situation more dire.

MA: Right.

RB: They were more fun-loving lefties. Let’s talk more about House of Meetings.

MA: I was having a real struggle [writing it] and it was about 10 months of that before it cleared. It was only in the last few weeks that I felt at all okay about it. And when the proofs came I picked them up with trembling hands at the last moment before they had to go back. And I have to say [I was] very favorably impressed and surprised.

RB: What was the amount of time between when you sent the manuscript in and receiving back the galley?

MA: Two or three months.

RB: When you turned it in, you did not have a good feeling.

MA: Right.

RB: You had trepidations; when you got it back they were gone. Isn’t that odd?

MA: It is. The whole thing was odd and it has not happened to me before. The other thing was that I was so convinced that it couldn’t stand alone that I had two short stories, one on either side of it, and was going to write a long introduction, to protect it, and then when I read it in proof I thought, “It doesn’t need protection: it needs air.” And was much longer than I thought. And this is weird—it read like someone else had written it.

RB: Have you moments of disembodied writing?

MA: No that was what was so difficult about it. Norman Mailer has written very well about this in The Spooky Art. When you come to a scene you expect your subconscious to have done a bit of the work, so that it’s ready. And it was as if my unconscious was unplugged. And was I having to gouge it out of nothing every time. It was a real effort of will and I kept thinking it wants me to abandon it, it doesn’t want me to write it. It’s begging me to abandon it.

RB: But you stuck with it.

MA: Stuck with it.

RB: Are there other novels that you have abandoned?

MA: No, there was one very early on. I only got about two pages into it. That’s such a terrible notion. The only comparable thing was with The Information. And that was to do with feeling terrible because I was getting divorced. Divorce is as bad as dying. So I was feeling so ragged and infested with failure of the marriage—

RB: But you were able to continue—

MA: Yeah, but there were moments when I thought, “I can’t do it.”

RB: That’s a substantial book.

MA: Yeah, it took me years to write it. That’s what—when I do these readings and people come up to sign books and if they have a lot of them I think, “I can’t believe I wrote so many pages.” [both laugh] And the thing about a book is, that also struck me, you have to write all of it—you can’t not write some of it. You’ve got to write all of it.

You think old age is a remorseless thing that gives nothing back. But it does give something back. And just as a man about to be executed who is going to be executed next week suddenly finds water, tap water, is delicious and the air, the air tastes sweet.

RB: In your home, where are your books?

MA: I haven’t seen them all lined up for years because we have been on the road. And they are all in storage. So it’s a shock to me to see all those.

RB: Do you bother to acquire the various translations [of your own work]?

MA: Yeah, one of each, I like to have. I don’t want six copies of the Czech Night Train. It’s nice to see them. It’s a pleasure to see them.

RB: But then again, it’s a psychological relief—it’s an image but you don’t think of the contents, do you? You are contemplating the sheer volume?

MA: Yeah, and some languages make the books much longer—what’s a medium-sized novel is fucking enormous in French. I don’t know why that should be.

RB: Maybe they changed the size of the type.

MA: Maybe—but a hundred pages longer?

RB: I spoke to you about 10 or 12 years ago for Time’s Arrow, and since you have done The Information, Experience, The War Against Cliché, Korba the Dread, Yellow Dog and now this. Have you any recollection what your thoughts on your future were after you completed Time’s Arrow? Was there a broad horizon in your vision?

MA: So I was what, 46 or 47? Uh, [long pause] I had a major mid-life crisis. Crisis by definition can’t go on being a crisis forever, can it? It’s got to resolve itself one way or the other. But now I am realizing you have a crisis every decade anyway.

RB: Something like that.

MA: Yeah, something like that. Actually, you think old age is a remorseless thing that gives nothing back. But it does give something back. And just as a man about to be executed who is going to be executed next week suddenly finds water, tap water, is delicious and the air, the air tastes sweet. Bread and butter make tears of joy come—it’s because you are sort of full of love of life because you are leaving it. And I’m not going to be executed next week but I am going to be dead sooner or later.

RB: Ten years, a la Joe Epstein.

MA: Yeah, another decade to go. But there is a bit of that departure affection that you have for the world.

RB: Have you read Everyman by Philip Roth?

MA: I have.

RB: Not a view espoused in that novel.

MA: No. [laughs]

RB: What did he say? “Old age is a plague…”

MA: It’s a massacre.

RB: I take it you haven’t had many of your friends die?

MA: Hmmm.

RB: We are not of that age.

MA: My oldest friend died, aged 51. My sister died, aged 46.

RB: That’s tough, but still you are not of the massacre point of view?

MA: No.

RB: Do you look at the obituaries?

MA: Yeah.

RB: First thing?

MA: No. [laughs] I’m not that morbid. But people who you have been aware of in your life and you think, “Christ, there goes another one.”

RB: Well, there is that yin-yang—dread of dying, or what you call “departure appreciation.”

MA: There is a lovely description of a lawn in a forest in Herzog [by Saul Bellow] and he just says, “Praise God.”—

RB: Did Saul Bellow’s death hit you hard?

MA: Yeah, but the wonderful thing about that, the palliative about that is I found I have been reading him pretty steadily since he is gone. And he is still there. In the books, that’s the marvelous thing about it. If you want to hang out with Saul, you read him. And in fact it has to be said that for the last few years of his life, he had no short-term memory—so it wasn’t like talking to the old Saul. It was more just a proximity to being near him rather than being able to exchange things with him. So I have had a great deal of pleasure rereading him. I am having dinner tonight with his widow, who is young, still young.

RB: He had a child when he was in his 80s.

MA: The oldest father in the history of the world. [laughs]

RB: Having children is great.

MA: It is. It opens you up and makes you vulnerable because you worry about them, and that doesn’t stop. I was just remembering when I interviewed Graham Greene, he was about 83 and he said, “Sorry, I’m a bit nervous. I am very worried—my son has flu.” I said, “How old is your son?” “58.” [both laugh]

RB: I spent a few hours doing a jigsaw puzzle with my son, which I am terrible at and he is quite good at, and I had a great time, and it was while we were doing it—the best thing in the world—and I couldn’t say why.

MA: They are not just physically beautiful, their presence is very beautiful and watching them thinking is beautiful, them working things out. And it’s wonderful to see the way they extend themselves into the world and they have more and more powers and more and more things they can do. It wonderful to watch that—it’s moving. Life is about accruing power and then towards the every end it’s about giving it up, painfully giving it up. But to watch the little ones working out what they can get away with—

RB: Sometimes they are like little lion cubs.

MA: Yeah.

RB: Given your well-expressed love of this country, will you spend any extended time here?

MA: It was very touch-and-go about whether it would be London or New York. My wife, who has lived in London—she’s a New Yorker, but she’s lived in London all her adult life pretty much—she wants to go back. Her mom is getting on and her stepfather, who she adores, as he said to me, may be the first person on the planet to say this, “I’m going to be fucking 80 next year.” [both laugh] And he is going to be fucking 80 next year. And she wants to be around them. And my boys will be—my daughter is 30 and my boys will be finished at university in a couple of years, and they’ll be done and they love coming to New York and their mother is often there—she is American. So it may yet happen.

RB: What would you do here?

MA: How do you mean?

RB: Teach?

MA: Maybe a bit of teaching. I am going to in England. Something I have never done, and my father was a very good teacher. I think I might have something to offer there. It will be energizing to come to New York after a couple of years in London. It will be just what we want.

RB: And the West Coast?

MA: It looks great, I must say. Apart from the traffic.

RB: You were just out there.

MA: Yeah, Los Angeles, that caring city.

RB: [laughs]

MA: The first thing I saw when I was being driven in, when we got into town and an old guy in a wheelchair crossing as fast as he could, the street, and someone in a tinted Mercedes, blasting on the horn, “Get out of the fucking way.”

RB: That’s done in all American cities.

MA: That’s what I love about Americans, they know their priorities.

RB: You are working in your next novel—any other projects? Narrating BBC series? Movies of any of your books?

MA: There is the usual nibble of options. That’s not going to involve me. Whatever happens.

RB: Do you care?

MA: It would be nice. David Cronenberg was reasonably close to making London Fields, but I knew it wouldn’t happen. I have never had a good experience with—I met him a couple of times and like him a lot.

RB: Do you want to do the script?

MA: I actually spent three weeks on that script, quite a long time ago, and then he redid it. But it’s not going to happen with him. Someone else might do it. So there is just a nibble of interest there every now and then. But no, I just see myself—I want to do the novels that I still have to do.

RB: I didn’t ask because I thought you were not satisfied with your work—

MA: Oh, I love it. Even when it’s, as with this one, very difficult, I wouldn’t want to be doing anything else. Just being alone with your books, your dictionary, and your library—that’s happiness for me. My wife has written a novel.

RB: She’s a journalist [Isabel Fonseca]. She wrote that fine book on Gypsies, Bury Me Standing.

MA: Yeah, the Gypsies book, a terrific book, a brave book. She lived with Gypsies in Albania and all that.

RB: That’s brave. Not a woman’s country.

MA: No, it isn’t. And she has written a novel and it’s good.